Over the weekend, news broke that the German security service had arrested a 31-year-old intelligence official who has been charged with providing classified information to an unnamed foreign government. Within a matter of hours, the German media confirmed that the country in question was the United States. CIA officials quickly said off-the-record that the Agency was ‘involved’ in recruiting the German agent, although we are still waiting for further details about what role the CIA played in this affair.

One should not be surprised by the news. You do not have to look very hard to find in the historical record information revealing that the CIA has been spying inside Germany for more than sixty years. CIA agents have even been captured and expelled by German authorities, including a number who were caught in the 1990s. These incidents, which received comparatively little attention in the U.S., were covered extensively in Germany and enraged the German public.

Despite the fact that Germany has been a longtime friend and NATO ally of the U.S., many of the Agency’s escapades have for decades been chronicled in the pages of the German news magazine Der Spiegel. And thanks to information leaked over the past year to the U.S. and European media by Edward Snowden, we now know in some detail that America’s eavesdropping behemoth, the NSA, had been tapping the cell phone calls of German Chancellor Angela Merkel and her predecessors since at least the late 1990s.

So why all the hoopla about this latest press revelation? Every foreign government official I have spoken to over the past thirty years has, at one time or another, admitted that they assume that the U.S. intelligence community is spying on their governments. A European intelligence official who has been actively involved in shaping the liaison relationship with the U.S. intelligence community since 9/11 admitted to me last year that, despite his country’s close relationship with Washington, this sort of clandestine behavior by America’s spies will continue well into the future. This is because espionage has become an integral part of American statecraft.

In the case of Germany, the CIA and the rest of the U.S. intelligence community have been actively conducting so-called ‘unilateral’ intelligence collection operations inside the country since the end of World War II. The CIA’s huge German Station, which was headquartered for most of the 1950s in the massive I.G. Farben Building in downtown Frankfurt, closely monitored every move of the hundreds of Soviet and Eastern European diplomats, as well as activities of the German Communist Party, which CIA analysts believed took its marching orders from Moscow.

These clandestine operations by the CIA were conducted with the knowledge and consent of the German foreign intelligence service, the Bundesnachrictendienst (BND), and/or the country’s internal security service, the Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz (BfV). This practice was codified in a secret document called the Contractual Agreement, signed on April 5, 1955 by the chief of the CIA’s German Station, retired U.S. Army Lt. General Lucian K. Truscott, and by Dr. Hans Glöbke, the special assistant for security matters to German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer. The agreement clearly defined and delineated what sorts of activities the U.S., British and French intelligence services could and could not do on German soil.

But in reality, the CIA and other U.S. intelligence agencies treated the terms of the Contractual Agreement more as a series of general guidelines rather than hard-and-fast rules of behavior. As will be detailed in a forthcoming document collection that I am currently completing, even after the signing of the Contractual Agreement in 1955, the CIA continued to secretly conduct clandestine intelligence collection and covert action operations inside Germany that were deliberately not disclosed to the German government.

These operations included the covert funding of a number of West German anti-communist labor groups and political parties, and spying on German opposition political parties. The CIA also used German anti-communist youth groups and political organizations as cover for establishing clandestine paramilitary resistance groups and “stay-behind” agent networks in case the Soviets invaded.

The CIA was also conducting a series of highly sensitive unilateral spying targeting the embassies and trade missions of a number of hostile targets, such as the Cuban embassy in Bonn and Iran’s large trade mission in Frankfurt. And the listening posts of the NSA quietly intercepted and decoded much of the diplomatic communications of the West German government right up until the day the Berlin Wall came down in late 1989.

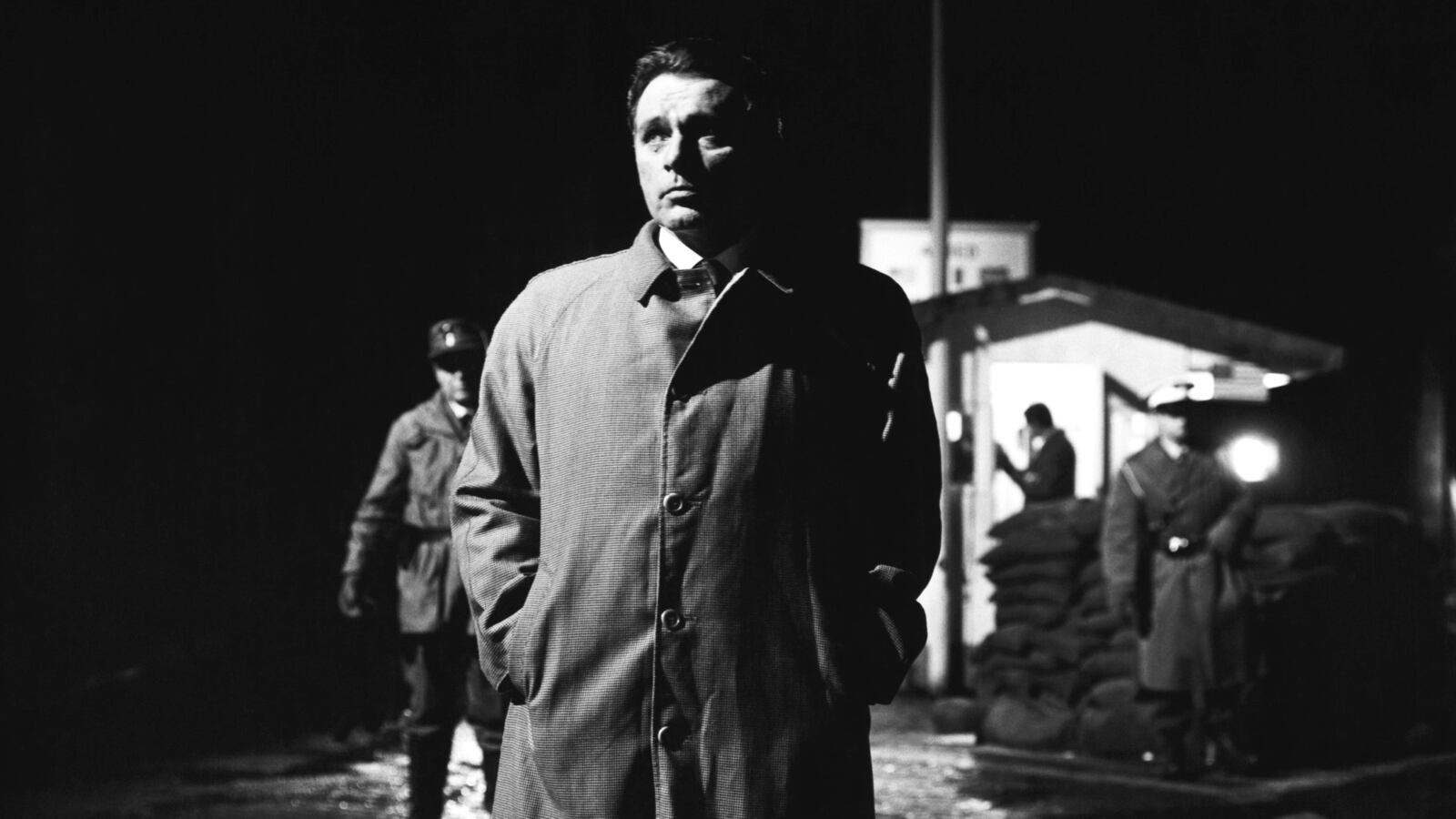

In West Berlin, where the BND never had a presence during most of the Cold War, the CIA’s Berlin Operations Base and a unit of U.S. Army intelligence monitored the activities of local German politicians. They also tapped the local telephone and telegraph lines and opened all German mail going to and from the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe.

But the tearing down of the Berlin Wall in November 1989, the reunification of Germany in October 1990, and collapse of the Soviet Union in December 1991 all had a tremendous impact on U.S.-German intelligence relations. Literally overnight, the ties that had closely bound the U.S. and German intelligence communities together throughout the Cold War were dissolved.

The U.S. intelligence community reduced the amount of data that it shared with the BND, and severely trimmed the financial subsidies that formerly had comprised a significant amount of the German intelligence budget. And in Washington political circles, a unified Germany was now viewed not only as a competitor to U.S. dominance in Europe, but also as an economic rival in global trade markets.

So not surprisingly, CIA spying inside Germany intensified significantly in the years immediately after the end of the Cold War, with much of the Agency’s focus shifting to German diplomatic, financial and trade relations with countries such as Libya, Syria, Iraq and Iran. The CIA’s intensified espionage activities inside Germany did not go unnoticed by the German internal security service, the BfV, which kept a watching eye on CIA case officers based in Germany, quietly noting which German government officials the Agency officers were talking to.

Then an event occurred which changed the way the German viewed the CIA’s espionage activities inside their country. In January 1995, the French government publicly declared persona non grata the CIA station chief in Paris, Richard L. “Dick” Holm, his deputy, and three other CIA case officers, including a female CIA officer who was trying to collect sensitive economic data from a French government official. France’s move convinced a number of senior German government and intelligence officials that perhaps the time had come to lay down the law about the CIA’s comparable economic espionage activities in Germany.

According to a former CIA official, in late 1996 the BfV caught a CIA officer attached to the U.S. embassy in Berlin trying to surreptitiously obtain confidential information about German equipment sales to Iran’s nuclear industry. The intelligence came from Klaus Dieter von Horn, a high-ranking official with the German Economics Ministry who headed the office in charge of trade relations with Iran. The BfV informed the German government, and Berlin demanded that the CIA officer be expelled from the country for “activities incompatible with his diplomatic post.”

A very public diplomatic fracas ensued in March 1997, when the German Foreign Ministry leaked to the German press that they had declared the CIA officer persona non grata and ordered him to leave the country. Furious efforts by the CIA station chief in Berlin at the time, Floyd L. Paseman, to convince the German government to rescind the expulsion order failed to achieve the desired result, and the CIA was forced to put the officer on a plane back to Washington.

If you thought that the CIA would have learned its lesson from the von Horn affair, you would be wrong. Two years later in September 1999, the CIA was forced to recall three of its undercover case officers stationed at the U.S. consulate in Munich who were caught by the BfV. The American spies had been trying to recruit another German government official with access to sensitive economic information.

According to a former German security official, two of the CIA officers were what are referred to within the CIA as NOCs (non-official cover agents), posing as a husband-wife team of American businessmen trying to collect information about German high-tech companies based in and around Munich.

The German Foreign Ministry wanted the CIA’s Chief of Station in Berlin, David Edgar, declared persona non grata and expelled from the country in order to send a sharp message to Washington that Berlin would not tolerate any more unauthorized behavior by the CIA. But the German Foreign Ministry was overruled, and Edgar was allowed to remain at his post until he rotated back to the U.S. in 2001.

A number of things bother me about the latest revelations about CIA spying in Germany. The first is that these sorts of highly sensitive clandestine operations apparently have not been curtailed in any meaningful way, despite President Obama’s repeated public pledges in recent months to impose restrictions on these sorts of activities.

And perhaps more importantly, given the massive amount of publicity given to the recent revelations about NSA spying inside Germany, why was this particular operation authorized in the first place? Is finding out what the German parliament is doing behind closed doors about the Snowden revelations worth the price of causing irreparable harm to U.S. diplomatic, economic and intelligence relations with Germany?