“I’d give ten years of my life to know Greek,” Mrs. Dalloway says in Virginia Woolf’s first novel, The Voyage Out. She has just heard a Mr. Pepper recite the famous ‘Ode to Man’ chorus from Sophocles’ Antigone, and the beauty of the language entrances her. Mr. Pepper, however, lacks the passion he inspires. He’s one of a long line of priggish bibliophiles in English novels, from Cecil Vyse in E.M. Forster’s A Room With a View to the suffocating Mr. Casaubon in George Eliot’s Middlemarch. Mr. Pepper may be able to quote Sophocles in the original, but Woolf’s narrator knows the true state of his soul: “His heart’s a piece of old shoe leather.”

Woolf’s novel suggests a gulf between the grandeur and romance of classical texts and the frequent pedantry of those who study them. She’s criticizing the injustice of an educational system that denied women the chance to “know Greek,” but she’s also pinpointing a subtler problem: that a certain type of classical education can extinguish the human faculties it’s meant to awaken. In his essay Such, Such Were the Joys, George Orwell recounts the horrors of precisely this sort of education at a boarding school where teachers used physical and psychological cruelty to motivate the study of Latin and Greek. An anecdote about a Columbia professor from roughly the same period reveals just how completely a certain approach to ancient works can miss their poetry and power. “Gentleman,” he supposedly opened the course by saying, “we shall begin with the most interesting play by Euripides: it contains nearly every exception to the rules of Greek grammar.”

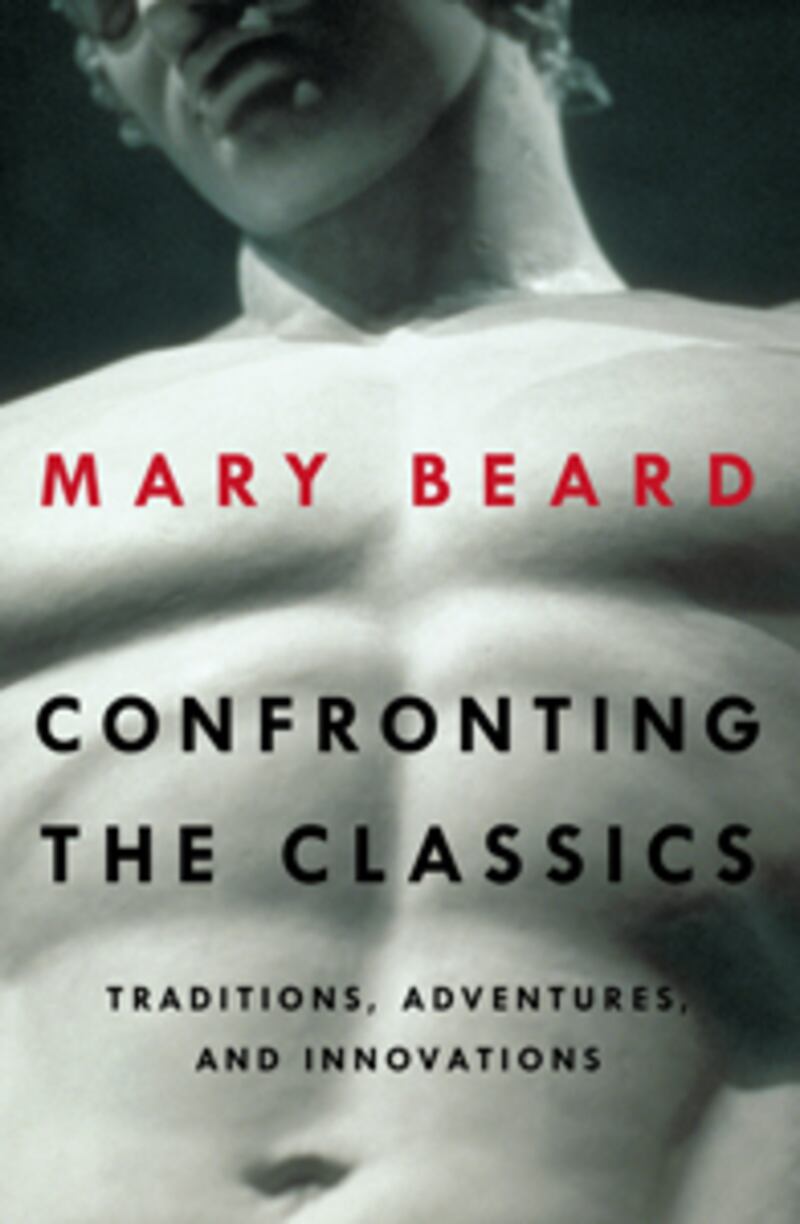

Most debates about the subject of Classics now focus not on how it should be taught, but on whether to teach it at all. Indeed, in 2011 UNESCO received a formal petition to declare Latin and Greek an “intangible heritage of humanity.” But as Mary Beard points out in the first essay of her new book Confronting the Classics: Traditions, Adventures, and Innovations , lamenting the decline of Classics has a long and illustrious tradition. Thomas Jefferson was already complaining in 1782 that the study of Greek and Latin was “going into disuse in Europe.” It’s striking to hear Jefferson sounding the alarm in an era when Greek and Latin were the foundations of elite education in Europe and America. And in 1902, a Cambridge Latinist offered this stark prediction about the future of Classics: “If these studies fall, they fall like Lucifer. We can assuredly hope for no second Renaissance.”

Beard, who is also a Cambridge Latinist, explains the persistence of the trope of decline from a golden age as a response to “the terrifying fragility of our connections with distant antiquity (always in danger of rupture), the fear of the barbarians at the gates and that we are simply not up to the preservation of what we value.”

The fact that previous predictions of the demise of Classics were wrong doesn’t necessarily mean current doomsayers won’t be right. But, as Beard points out, the considerable market for articles and books lamenting the decline of classical learning does suggest some appreciation for its value. The perennial feeling that Classics are imperiled also generates a consistent supply of popular works intended to rescue the ancient world from oblivion. This group, broadly conceived, includes everything from Sir Francis Bacon’s 1625 The Wisdom of the Ancients to HBO’s Rome.

Beard’s essays reveal a nuanced understanding of some of the perils and paradoxes of popularization. One interesting case study is Sir Arthur Evans, the original excavator and “restorer” of the Minoan palace of Knossos on Crete. Evans bestowed grand names like the “Hall of the Double Axes” and the “Queen’s Megaron” on the rooms he found, and his artists embellished the fragmentary wall paintings with lush and evocative scenes. One restoration depicted a young boy gathering flowers; only later did someone realize the boy had a tail and was probably a monkey. When Evelyn Waugh visited the site in 1930 he noted that the artists behind the restorations seemed to have “a somewhat inappropriate predilection for covers of Vogue.” The public shared the predilection. In the 1888 Baedeker guide to Greece, Crete wasn’t even mentioned. Today the site receives a million visitors a year.

A linguistic version of this phenomenon occurs in translations of the notoriously challenging Greek of the historian Thucydides. Translations into clear and readable English actually fail to convey the stylistic obscurity and difficulty of his Greek. Thus the “good” translations also tend to be the least accurate, “rather like Finnegan’s Wake rewritten in the clear idiom of Jane Austen,” as Beard puts it. One of the most quoted lines from Thucydides is usually rendered like this: “The strong do what they can, the weak suffer what they must.” A more precise translation would read: “The powerful exact what they can, and the weak comply.” The gulf between the two translations might not be as dramatic as the difference between a monkey and a boy, but the shift in meaning and emphasis is crucial.

Beard isn’t claiming that every popularization is an unpardonable misrepresentation or simplification. She savors various transformations of classical material, from Bobby Kennedy’s (mis)quotation of Aeschylus after the assassination of Martin Luther King to the improbably popular French children’s books starring Asterix, a feisty Gaul resisting Roman conquest. She also praises the works of non-academics like Stacy Schiff, claiming that one line of Schiff’s biography of Cleopatra captures the politics of ancient Rome more aptly than “many pages written by specialist historians.”

Beard does admonish the tendency of both academics and popular authors to present speculation as historical truth. The fragmentary nature of ancient evidence often presents an impossible challenge to biographers interested in telling a modern “life story” with equal degrees of detail on each phase of life. (Childhood in particular did not seem to interest ancient sources.) Rather than frankly acknowledging these gaps, many biographers invent things. Schiff, for instance, conjures a scene with the young Cleopatra “scampering down the colonnaded walkways of the palace.” Plausible fantasies acknowledged as inventions are certainly preferable to anachronistic fictions masquerading as facts, but I think Beard wants to make a different point: the surviving evidence is sufficiently weird and interesting that embellishments are superfluous.

Beard’s essays in this volume range from humor in ancient Greece to the reputation of the emperor Caligula to the restoration of Roman sculpture. She writes with grace and wit on a vast array of subjects, and she has a novelist’s gift for selecting odd and revealing details. We learn, for instance, that Augustus’ wife Livia had a competition with his granddaughter Julia over who owned the smallest dwarf. (The winning dwarf belonged to Julia and was 2 foot 5 inches tall.) We also see glimpses of Roman popular culture through the Oracles of Astrampsychus, a fortune-teller’s book from the second or third century A.D. that offered randomized answers to all sorts of questions. Some are eternal worries (“Will I be prosperous?”), while others are less relatable (“Have I been poisoned?”). One of the pleasures of reading Beard is her capacity to remind us that although Greek and Roman cultures often seem familiar, they remain elusive in basic ways.

As for Mrs. Dalloway, she never traded ten years of life for the knowledge of Greek. Virginia Woolf, however, did read Greek; she was translating Sophocles while she was writing Mrs. Dalloway. Around the same time she wrote the essay “On Not Knowing Greek,” which muses on the difficulty of understanding the ancient Greeks, even for those who know their language. Woolf admired Sophocles and Euripides, but she saw in Aeschylus something sublime, the capacity to capture “the meaning just on the far side of language.” However many years of life she traded to learn Greek, she had found the exchange worthwhile.