In modern Republican politics, you either adapt or you die. Once a thorn in the side of GOP leadership and a pariah of the Republican establishment for challenging moderate Republican incumbents, the Club for Growth is adapting: “There’s a new Club for Growth,” says David McIntosh, the group’s fourth president.

Actually, it’s been more of an evolution than a rebirth.

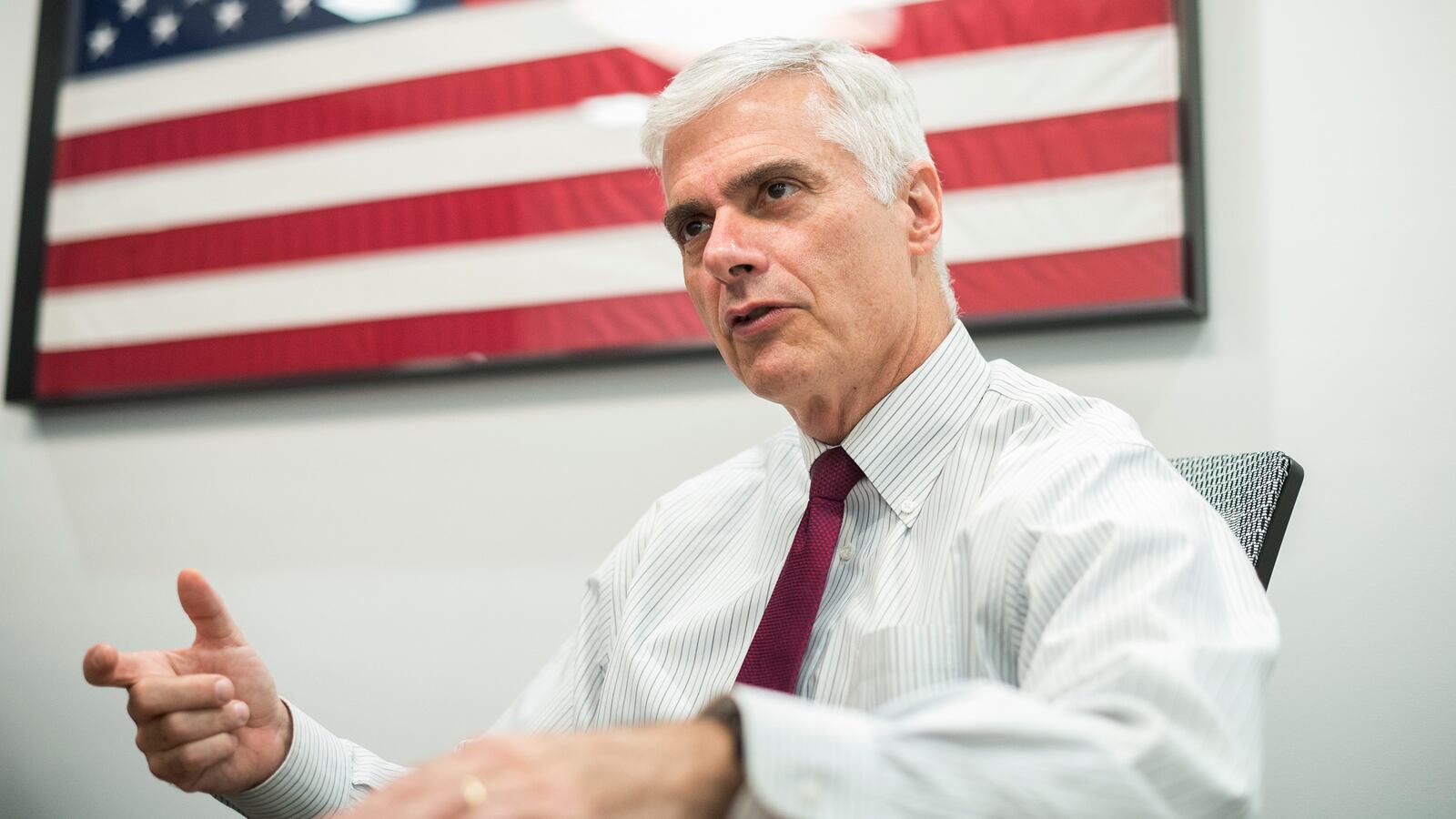

“We want to be the political arm of the conservative movement—inside the Republican Party,” McIntosh, a former Indiana congressman and co-founder of the Federalist Society, stresses when we meet at a Starbucks in downtown D.C. (Disclosure: I’m friendly with McIntosh and have moderated panel discussions at Club meetings.)

During the height of the Tea Party, the Club reveled in sticking it to the man. In many cases, this involved challenging establishment incumbent Republicans. But in recent years, it shifted strategies, going so far as to have its Super PAC coordinate with Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell’s Super PAC (sharing polls, dividing up races, etc.) during the 2018 midterms. (As recently as 2013, the club was considering backing a primary challenge against McConnell.)

Some of this reinvention was predictable. The Club helped elect Ted Cruz, Marco Rubio, Ben Sasse, and Pat Toomey, so it makes perfect sense to focus on defending their investment. But it’s also an admission that times have changed—to remain relevant, the Club will have to change with them.

Though McIntosh doesn’t rule out ever challenging an incumbent again, part of being the conservative movement’s political arm inside the GOP means playing nice and patching up old wounds.

Phase One was to atone for their opposition to Donald Trump in 2016. “Last cycle it was critical for the survival of the Club for Growth to pivot from having opposed Trump in the presidential primaries to being affirmatively supportive of Trump in the policy battles,” McIntosh says.

What is more, since 80 percent of the primary voters want a candidate who will be loyal to the president, he tells me, “If they’re a Never Trumper, we’re not going to support them.”

Not only that, the Club will use a candidate’s opposition to Trump as a convenient cudgel. McIntosh mentions Bradley Byrne, a Republican congressman from Alabama, who is running for the U.S. Senate in 2020 (hoping to win the nomination to face incumbent Democrat Doug Jones). Back in 2016, in the wake of the Access Hollywood video, Byrne made the mistake of criticizing Trump. McIntosh (who prefers Rep. Gary Palmer in the primary) suggests to me that Alabamians will be reminded of this in the upcoming Senate primary.

The irony, of course, is that the same Club for Growth that opposed Donald Trump in 2016 is now imposing a purity litmus test against Republican politicians who weren’t sufficiently loyal to Trump in 2016.

Here, it’s worth spending some time thinking through what it means for a group like the Club for Growth to pivot and fully embrace Trump. At a time when internal feuding can hurt the party, having folks on the same page makes electoral sense. Additionally, there’s no need to spend money against the very conservatives you previously helped elect. But the downsides are obvious: At a time when spending and deficits and debts are clearly out of control, they've basically said we aren't going to fight those electorally. There's a defeatism to that and it should sadden folks who still care about those issues.

Like Lindsey Graham, there’s an argument for staying relevant and maintaining influence. The alternative is to go the direction of Jeff Flake—a former Club for Growth favorite—who stood up to Trump and found himself out of a job. Trump has won, and whether it’s tax cuts, deregulation, or conservative judges, there is much for a fiscal conservative group to cheer. And if you want to help steer the conservative movement’s future, you have to stay in the game. That, in my estimation, is the calculation.

Having dealt with the Trump problem, Phase Two involves demonstrating they can help the GOP win general elections. Luckily, one argument for the Club becoming the conservative movement’s political arm within the GOP is that they’re pretty good at it.

It has long been known that political consultants pad fees and bilk candidates, sometimes diverting funds that might have been spent actually persuading voters. And new research suggests this problem is even more pervasive on the Republican side. By keeping close tabs on their political consultants and vendors, the Club has cultivated an exemplary win-loss record, while keeping overhead expenses to a bare minimum.

They’re also working hard to be more innovative and daring than the politicians they support can afford to be. For example, social pressure is probably the most effective way to motivate someone to vote, and the Club isn’t above exploiting this psychological phenomenon.

During the 2018 midterms, the Club sent out mailers targeted to conservative voters that publicly disclosed the names and turnout rates of their neighbors. There was no advocacy for any candidate, just a mailing to imply that your neighbors know if you’re a good citizen who does—or does not—vote.

To test their effectiveness, the Club also sent out normal mailers about hot-button political issues. The result? “The ideological pieces didn’t increase turnout,” McIntosh says, but the social pressure mailers had a 2.6-percent lift in turnout. Millions of these were sent around the nation. And when he does the math—when he calculates how many of these mailers (and texts) went out in Florida and factors in the 2.6-percent lift in turnout—McIntosh presents a pretty compelling case that the Club elected Ron DeSantis and Rick Scott.

Being a political arm often means being up to your elbows in muck and discovering some pretty disturbing things when your invisible hand starts prodding around the electorate’s dirty underbelly.

Probably the most disturbing story I heard was this: McIntosh tells me that the Club tested a 2018 TV ad in Texas about how as El Paso councilman in 2006, Beto O’Rourke supported using eminent domain to bulldoze a historic Hispanic neighborhood. The plan was ultimately abandoned, but hard feelings linger. The most disturbing discovery? White voters whom the Club polled were actually more likely to vote for Beto over Ted Cruz after hearing Beto wanted to bulldoze that Hispanic neighborhood.

“It was eye-opening,” McIntosh admitted. McIntosh wasn’t happy about what he found, but it informed the Club’s strategy. A version that mentioned eminent domain (but not the Hispanic neighborhood) ran on broadcast TV, while the ad mentioning the Hispanic neighborhood was targeted to digital ads and Spanish TV.

Back to the Club being the political arm of the conservative movement inside the Republican Party. One of the good things about having an arm is that it can get chopped off without killing the body. In the case of the Florida social pressure campaign, the 1-888 number listed on the flier resulted in more than 25,000 angry phone calls from people who felt that their privacy had been violated (whether you vote is a matter of public record), McIntosh says. Still, angry phone calls are a small price to pay for electing a Republican governor and senator.

The good thing about the Club running aggressive operations is that complaints don’t tend to blow back on the actual candidates. This is one reason why candidates don’t—and probably shouldn’t—try this at home. It’s also an argument for why the Club, even in the post-Tea Party Trump era, is still relevant.