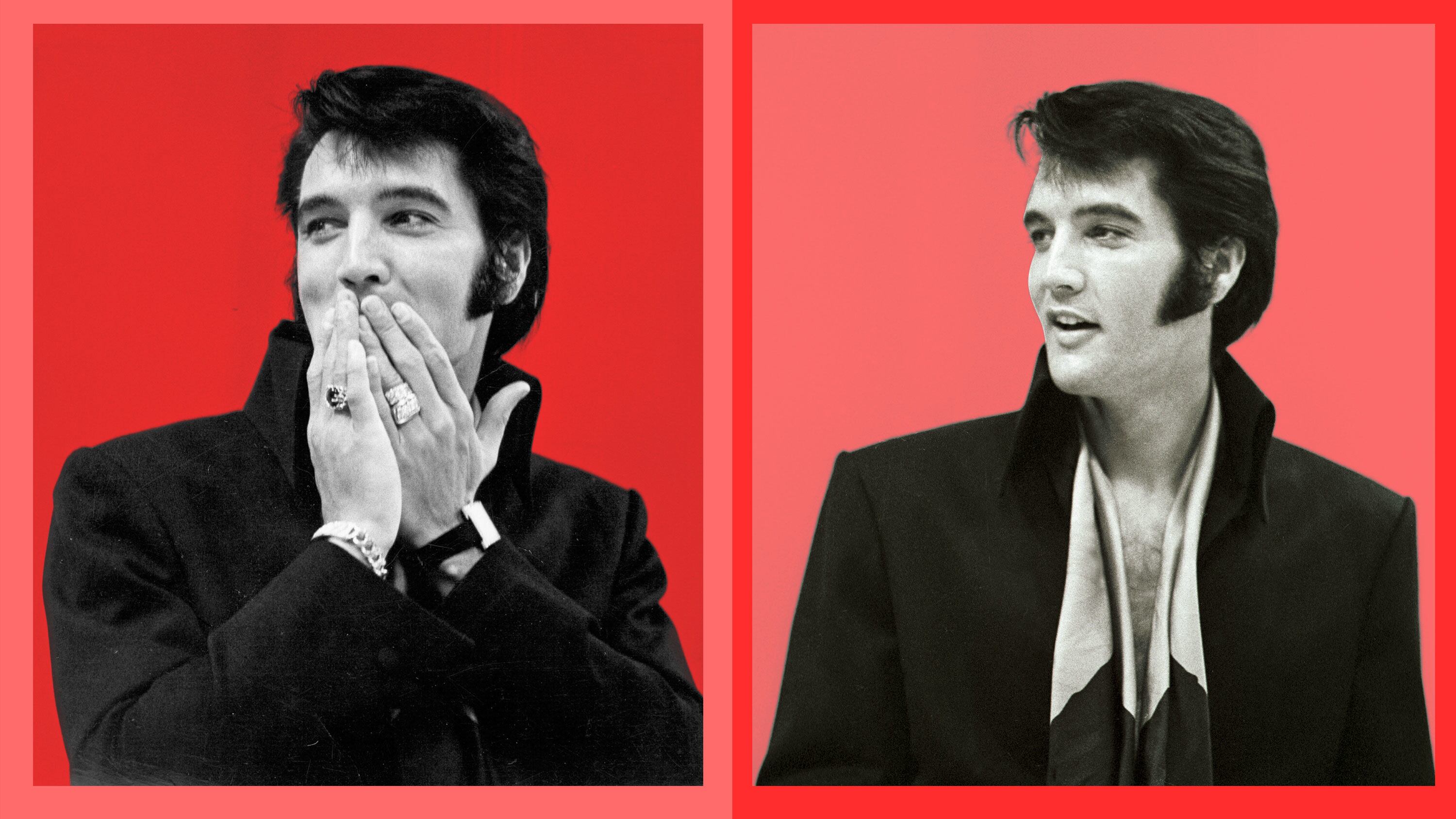

Reading Elvis in Vegas by Richard Zoglin requires a journey into YouTube, to watch the same videos Zoglin used in his book’s research. There’s Presley, high-collared jumpsuit opened halfway down his chest, huge shock of black hair, heavy eyes and thick cheeks, lips curved into a half-smile of a hidden joke.

His Las Vegas concerts have sweetened through the ages just like wine.

Elvis taps his leg, swings his arms, kicks and spins on the International Hotel’s stage without the pretense of choreography. Behind him, the stage is filled with an orchestra, two singing groups, and a full rhythm band; all a spectacle never really seen before.

We know that Elvis’ 1969 Las Vegas comeback began his life’s twilight—but from the purple haze of Nevada’s western desert, Zoglin recaptures the horizon-filling blast of that spectacular sunset.

Other artists still play under bright lights. In their 2019 performances of “Gimme Shelter,” the Rolling Stones carry Altamont’s 1969 DNA. The Beatles rooftop farewell came the same year, but Paul McCartney sounds the same today. In those occasional tours, we can breathe 1969’s rarefied air.

Not from Elvis, though. Elvis is long gone, back to Memphis on the Mystery Train.

When unaccompanied by music and minus the sound of his voice, Presley’s career feels like a mental montage of clichés: Ed Sullivan, his Army uniform, a movie snippet from Viva Las Vegas, the big white jumpsuit, and a sweaty brow. Time compresses him into these moments, mediocre in their equality.

But watch a three-minute concert video and here we go again; that’s where he’s been. Kick up a pile of golden leaves, burst them apart into memories of the color and the sound.

It took some doing, Zoglin writes, to earn that brief Vegas redemption. By 1969, Elvis’ movies had flatlined, and his ’50s teen idol days were long over. He needed a breakthrough, and Vegas—certainly not New York’s upstate cow pastures—was the pinnacle of splashy, showroom entertainment.

Though bolstered by a successful 1968 TV special, Elvis had not performed for a live concert audience since 1961. In putting the Vegas shows together, he even had some trouble finding a backing band; session work back in Nashville paid better than a month of stage appearances with a 34-year-old thinking he could still sing teenage rock-and-roll.

“This was virgin territory as far as a rock-and-roll performer,” Zoglin told The Daily Beast. “He had the guts to take it on without any real help, to construct a new kind of show. It was a great act of creative reinvention.”

“Elvis showed how to make a comeback,” Zoglin said.

Today, Elvis’ influence is easy to overlook. Modern-day artists have magnified and fine-tuned Presley’s approach to Vegas. Madonna, U2, Lady Gaga, Taylor Swift, and Kanye West make Elvis look barely quaint—but in 1969, that’s not what people expected of their concerts.

Elvis debuted at the International Hotel (later the Las Vegas Hilton and now the Westgate) on July 31, 1969. Woodstock was just three weeks away, but take away the festival’s half-million attendees, and it featured a fairly standard stage without much in the way of light shows or decoration. In 1966, the Beatles played to record-setting audiences from a standard square stage, wearing conservative black suits with no dramatic production elements.

That’s no criticism of these legendary performances; pre-Elvis, any flashy style simply took a backseat. On a smaller scale, James Brown, Little Richard, and Jerry Lee Lewis knew how to raise the roof, but Elvis in Vegas gave the first large-scale roadmap for how to provide both.

It is the ’60s’ inherent conflict between those two sides that Zoglin recounts from many angles. Before Elvis, it was Frank Sinatra who ruled Vegas with a dinnertime cool. Young stars like Bobby Darin wanted to be like him—controlling the stage in the solo spotlight. By 1969, Darin no longer saw substance in copying Sinatra’s black tuxedo, and Zoglin writes “he dumped the tux in favor of jeans and a denim jacket, replaced his orchestra with a rhythm quartet, and insisted on being billed as Bob Darin.”

Like any change driven partly by outside forces—Robert Kennedy’s assassination, Civil Rights, Vietnam—Zoglin writes that Darin’s sudden shift veered into self-righteousness and rankled audiences and friends.

“Go back and put on the tuxedo and go to work,” Dick Clark lectured Darin. “Do what the people expect of you.”

To play a Vegas showroom was, at heart, a subset of the service industry—not an ego trip. Barbra Streisand learned that the hard way as the International Hotel’s inaugural act. Zoglin writes that she made jokes about the unfinished hotel and sang songs with only a minimal emotional connection to a casino audience that expected some schmoozing.

“[Streisand’s] a sweet girl, but she had that New York mentality,” Bobby Morris, then the International’s music director, told Zoglin. “There was too much wisecracking. She seemed above it all.” Elvis agreed: “She sucks,” he told one of his crew after he saw her show.

Elvis had gotten his own negative notes at his 1956 Vegas debut. His “dirty baseball jacket” didn’t fit the New Frontier casino, comedian Shecky Green told Zoglin. But Elvis learned from his mistakes, and Zoglin writes that Elvis enjoyed attending shows and getting ideas from his fellow performers. Tom Jones’ more mature sexual energy was something Elvis knew he wanted to emulate.

Elvis also noticed how empty Streisand’s production felt on the International’s sprawling stage. He prepared for that size and scope—his show would fill the stage in a way unprecedented in rock entertainment. His manager, Colonel Tom Parker, had originally proposed conventional “showgirls and production numbers, maybe something like the dancing jailbirds in Jailhouse Rock,” Zoglin writes. Elvis wasn’t having it.

Elvis “had a dream… a Vegas stage filled with a huge collection of musicians: a rhythm band, two backup singing groups, and the biggest orchestra Vegas had ever seen… the Colonel balked and said plans were underway for something much different. Elvis insisted that he would do the show he wanted or not at all. It was the first time, he told friends, that he actually hung up on the Colonel,” Zoglin writes.

“With all the activity on stage, all the movement, Elvis created his own extravaganza,” Zoglin told The Daily Beast. “Elvis himself filled that stage.”

It’s just like how Elvis fills Elvis in Vegas: Once he takes the stage, everybody else falls away. The book’s concept began as an account of ’60s Las Vegas show culture, an unexamined aspect of a city where the mob, gambling, and the epic history of the casinos are well-documented. In a way, the era of Elvis in Vegas is a whiskey-neat prequel to the cocaine-fueled ’70s stand-up comedy culture that Zoglin previously examined in Comedy at the Edge. In that book, equal treatment of the subjects worked fine—George Carlin could share space with Steve Martin and Richard Pryor. They’re all equals, peers.

Elvis has no peer.

Zoglin’s publisher suggested Elvis become the book’s framing device and it was a necessary choice to highlight that era’s cultural shift. By 1969, even Vegas audiences needed more than Frank Sinatra’s retro class or Shecky Green’s corny jokes.

“What happened as Elvis supplanted Sinatra is a mirror of what was happening in the wider culture,” Zoglin said.

So it’s not Sinatra’s fault he’s too much conversation. Elvis is the action.

Ultimately, Elvis in Vegas is like what Myrna Smith said about her trio, the Sweet Inspirations, which opened each night’s show with a 20-minute set:

“The audience was very good to us. We knew that they were there for Elvis, and we knew they wanted us to get off the stage as fast as possible.”

The Inspirations returned to back up Elvis alongside the male gospel quartet, the Imperials. James Burton, Ronnie Tutt, Glen D. Hardin, and others made up the rhythm band, further supported by a 40-member orchestra. The $80,000 payroll came out of Elvis’ pocket, Zoglin writes, and Col. Parker took out his annoyance by pointedly snubbing anybody not named Elvis.

“Yet the Colonel gave Elvis no pushback; for his big return to the stage, Elvis would have all the company he wanted. The musicians onstage represented a grand coming together of all the music Elvis loved and that had shaped him as a singer,” Zoglin writes: rock, country, gospel, rhythm and blues.

“This was the deprived musician, who had not been able to control his music,” longtime Elvis friend Jerry Schilling told Zoglin. “And now he was going to satisfy all his musical desires.”

Though he was very involved in arrangement and production, Elvis never wrote a full song of his own—his co-writing credits were often a profit-making arrangement. Still, even if he only wrote a lyric here or there, Elvis was probably the best interpreter of music who ever lived.

“He always focused on the story of the song,” said bassist Jerry Scheff. Not even an Elvis fan, Scheff had auditioned for the Vegas band out of curiosity. “It was like the words and melody went through his brain, then to his heart, and then came out of his mouth. When Elvis started singing, I couldn’t believe how natural he sounded.”

American Idol’s Simon Cowell used to criticize contestants for singing “karaoke,” pointing out that emotional connection is what the youngsters lacked. They sang by rote—carrying Whitney Houston’s high notes, but not feeling them.

Elvis’ peerless skills are heard in Mac Davis’ melodramatic “Memories.” Lesser singers would be overwhelmed by the schmaltz and silliness that make it so hard to not wink at the audience, to let them know the singer’s not taking it that seriously.

Lyrics like “Of holding hands and red bouquets,” “Laughing eyes and simple ways.” Who could get away with that?

Elvis could, as easy as Sunday morning. His maple syrup baritone captures “Quiet nights and gentle days,” finishing “with you…” in almost a whisper. His sexiness transcends gender.

“It is the essence of Elvis,” Zoglin writes. “Schmaltz raised to the sublime.”

Even a goofy song like “See See Rider” sounds like Elvis storming out the door—he’s looking for a good girl, but who’s he kidding? He’ll come back to the easy rider that done him wrong. In many live recordings, Whitney’s mother Cissy is one of the Inspirations backing him up with a full-throated “yeah, yeah, yeah.”

Following his one-show July 31 debut, Elvis played two 70-minute shows for 28 straight hot August nights, at 8 p.m. and midnight. Tickets were about $15, which adjusted for inflation is about $100. A fair price since it usually included dinner. He crashed each night and got up around 5 p.m. to do it all again.

Over the years, the myth has taken hold that Elvis could only play Vegas, that the shows were his desperate clutching at squandered fame, in a city already a failing wasteland.

It was the opposite. He wanted to play Vegas because in 1969 it was the only place big enough to deserve him. After his shows, John Lennon and Bob Dylan peppered journalists with questions: “Did he do the Sun stuff? Did he do ‘Mystery Train?’ Who’s in the band?” Dylan asked one reporter, writes Zoglin. “Everybody was a fan again.”

Elvis’ then-wife Priscilla had never before seen her husband unleashed upon an audience: That night, “I got it,” she told Zoglin. “He owned that stage.”

That redemption has been lost to time’s compression. Months of back-to-back shows meant amphetamines on the up, sedatives on the down, and something else to mellow the in-between. All the Vegas shows—600+ over 15 different residencies from 1969 to 1976—condense into overweight Elvis, sweating, splitting his pants, swooshing on stage with a Dracula-like cape.

The ending’s the ending. But that ending wasn’t the triumph of 1969.

“I wanted to redeem Elvis a little bit, overcome that popular conception of his decline and his weight and his drug use,” Zoglin said. “I wanted people to remember that he was a great stage performer and his voice was great. In Vegas, he reinvested himself in the music.”

Music aside, the cultural shift that let Elvis supplant Sinatra was far wider and deeper than a month of concerts could forestall. One showroom’s success would not hold back 1970’s explosion of arena rock. Artists like Led Zeppelin or the Eagles or Bruce Springsteen took their music across the whole country, and Vegas wasn’t cool, when 15,000 stoned teenagers could scream a singer’s name. The new breed copied the Rolling Stones’ concert model, bringing the spectacle to everybody, everywhere. It was Elvis’ bad luck that his own performance quality declined along with Vegas’ musical appeal, leaving ’70’s memories of both with that same low-rent vibe.

“It all got to be kind of ridiculous,” Zoglin said. “His voice held up, but the cape, the white suit, the increasing bombast of the shows, it became a parody of itself. The look became synonymous with how people thought of the empty Vegas glitz.”

But not in 1969.

Zoglin’s book does what he wanted—it brings readers all the way back to that last cresting surge in Elvis’ mighty career. Before, as Hunter Thompson observed from Las Vegas in a different context, “the wave finally broke, and rolled back.”

Lester Bangs wrote the still-perfect summation of Elvis with his 1977 Village Voice obituary, which contained a line that also foreshadowed 2019’s toxicity: “If love truly is going out of fashion forever, which I do not believe, then along with our nurtured indifference to each other will be an even more contemptuous indifference to each other’s objects of reverence.”

He meant how Elvis had fallen out of favor by 1977, a relic of an old and tired time. That year’s punk and disco fans wanted nothing to do with him. Even if disco’s drama and emotion descended from Elvis singing “Suspicious Minds.” Even if punk’s rebellion built on Elvis’ hip swivel and sneer. It’s easy to deride what we don’t love, instead of figuring out why somebody else does. The Last Jedi, Little Mermaid, Korean K-Pop: all 2019’s Fat Elvis to sour fools who sneer at someone else’s little flash of excitement over something new, or just a new way of seeing what is old.

Elvis’ invisible influence is everywhere in 2019—the Vegas residencies by Celine Dion or Garth Brooks; in LeBron or Beyonce’s one-name celebrity; in the elegiac storytelling of Bruce Springsteen on Broadway, a show surely crafted with the awareness that Elvis failed to control his own legacy.

To visualize that lost era, Zoglin studied Elvis’ live performances over and over again.

“The movements, the vocals, what can I say, I loved them more each time I watched them,” he said. “I couldn’t get enough.

“The only time I felt sad was one later show, and I saw how far Elvis had deteriorated,” Zoglin said. “He was overweight, hardly moving. It was kind of heartbreaking.”

That last image remains in appearances like June 19, 1977, two months before he died. Elvis is in Omaha, Nebraska, chasing that arena money. He looks terrible. The white jumpsuit highlights a bloated belly. His sweat drips on the microphone. He hunches over a piano to sing “Unchained Melody.” Time can do so much.

Then here come the high notes, and here comes the voice; time goes by so slowly, and he needs your love. Here’s the hope, the consolation, the strength to carry on.