The days of the International Space Station are numbered. NASA plans to retire the floating research hub by 2031, nudging it closer and closer to Earth until it splashes into a watery grave in a remote part of the Pacific Ocean, like so many spacecraft before it.

What comes after will look nothing like the flag-waving, handshaking diplomacy of the multinational research vessel, a post-Cold War olive branch between the U.S. and Russia, built and operated with Japanese, Canadian, and European allies. Low-Earth orbit (LEO)—the area about 100 to 1,200 miles above the planet, where the ISS has remained continuously staffed since 2000—is primed for a takeover by the free market. Rather than build its own successor space station, NASA is grooming other companies for American replacements.

“NASA has publicly said it doesn’t want to do another thing like this. It turned low-Earth orbit over to the private sector for development,” John Logsdon, a professor emeritus of political science and international affairs at George Washington University, told The Daily Beast. “It’s the next chapter in humans utilizing space.”

The International Space Station (ISS) is seen from NASA space shuttle Endeavour after the station and shuttle began their post-undocking relative separation May 29, 2011 in space.

NASA via GettySpace for Rent

NASA is promoting a new era of commercialization in LEO. The agency will become a customer—optimistically, one of many—that rents space, time, and equipment from landlords of commercial LEO destinations, or CLDs. It will maintain a foothold at the threshold of outer space without having to foot the whole bill.

“NASA envisions a bright future for the LEO economy,” reads the January 2022 International Space Station Transition Report. “By the early 2030s, NASA plans to purchase crew time for at least two—and possibly more—NASA crewmembers per year aboard commercial CLDs to continue basic microgravity research, applied biomedical research, and ongoing exploration technology development and human research.”

The transition is underway. Next month Houston’s Axiom Space will launch the first civilian mission to the ISS. In 2024, it will attach its own module to the ISS. When the station is decommissioned, Axiom’s module will separate to become the first free-flying commercial space destination in history.

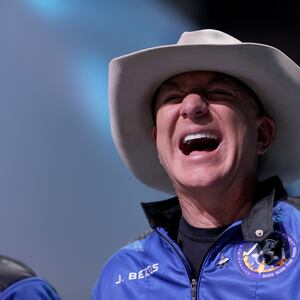

And the agency isn’t simply putting its eggs all in this one basket. In late 2021, NASA awarded $130 million to Blue Origin, $160 million to Nanoracks, and $125.6 million to Northrop Grumman to help fund the design of three more private space stations over the next four years.

“With commercial companies now providing transportation to low-Earth orbit in place, we are partnering with U.S. companies to develop the space destinations where people can visit, live, and work,” NASA Administrator Bill Nelson said in a statement in December 2021.

When President Ronald Reagan announced the plan for a new space station during his 1984 State of the Union address, he told the country: “America has always been greatest when we dared to be great. We can reach for greatness again. We can follow our dreams to distant stars, living and working in space for peaceful, economic, and scientific gain.”

Sales pitches for the commercial stations of the near future strike a glossier, less schmaltzy tone.

Marketing copy for the Orbital Reef space station concept reads like a brochure for the Marriott Marquis. A collaboration of Blue Origin and Sierra Space, along with Boeing and others, the “premier mixed-use space station” will offer “out of this world research facilities,” “big windows” and “breathtaking views of our home planet, with 32 vibrant sunrises and sunsets each day.”

Conceptual art of the interior of the Axiom Space Station module as envisioned by Philippe Starck.

Axiom Space“Whether your business is scientific research, exploration system development, invention and manufacture of new and unique products, media and advertising, or exotic hospitality, you’ll find a berth here,” the Orbital Reef website promises. It is supposed to open by the end of the decade.

Not to be outdone, Lockheed Martin plans to build the “spacious” inflatable habitat for Nanoracks’ Starlab, debuting in 2027. Starlab’s main feature is the George Washington Carver Science Park, with biology, plant habitation, physical sciences and materials research laboratories.

Even Axiom has gone out of its way to ensure its space station has a sleek, enticing draw that attracts wealthy visitors and makes them feel like their sojourn in space has a luxury feel. Axiom’s crew accommodations were designed by Philippe Starck, the famous French architect who created the iconic Ghost Chair and has lent his flair to more than a few luxury hotels around the world. “The egg-like structure symbolizes nest-like comfort complete with unobstructed views of our home planet—the first such place for humans to truly contemplate our place in the Cosmos,” according to Axiom’s website.

NASA astronaut Sandy Magnus mission specialist for space shuttle Atlantis STS-135, takes in the view while sitting in the Cupola addition of the International Space Station July 16, 2011 in space.

NASA via GettyLet's Get Down to Business

For NASA, the next decade will be the space station’s “most productive,” as astronauts learn more about how to sustain life in low-Earth orbit and beyond—research imperatives to enable future missions to the moon and Mars. After that, the agency will use CLDs as proving grounds for biological experiments and new technologies.

Outside NASA’s official business, Casey Dreier, a space policy expert at The Planetary Society, expects the first significant commercial pursuits will be in Earth observation—monitoring the globe for sellable data on things like deforestation, climate change, land use, human migration, natural disasters and war. “The most commercializable aspects of space are the stuff that allows us to turn back inwards on ourselves, taking pictures of our own planet, talking to ourselves, connecting to each other,” he told The Daily Beast, referencing efforts from companies including SpaceX and Amazon to deploy tens of thousands of small satellites for global high speed internet. “Those are the things that have existing markets.”

The more tenuous promise of the private industry’s entrance into space lies in putting humans in space, “extending capitalism up to the moon” and creating a so-called cislunar economy, said Dreier. Think: mining the moon’s surface for water to create rocket refueling stations, or establishing lunar colonies.

And space tourism? Sure, “if you get the price down,” according to Logsdon.

On the other hand, maybe what comes next is… nothing. “After the station is deorbited, maybe there is no enthusiasm for continued activity involving human presence in low-Earth orbit,” Logsdon posited. “It’s fundamentally boring just going around in circles. I think it’s way past time that we leave the immediate vicinity of Earth and go somewhere.” He’d like to see people living and working on the moon: “That’s the first step to us becoming a spacefaring species—people are born, live, and die someplace other than Earth.”

To hear him tell it, the loss of the ISS isn’t much of a loss at all. The hulking behemoth, he sniffed, was always bigger than it needed to be and too troublesome to maintain. What’s more, the learnings derived from research on board—while laudable—are of limited utility. “The experience in long duration spaceflight will be extremely useful when we go to Mars,” Logsdon said, “but not particularly relevant to returning to the moon. It's only three days away.”

And for all the excitement of what’s to follow, companies aren’t necessarily clamoring to fill the gap.

“What is supposed to have happened by now is that governments had demonstrated the multiple payoffs from an outpost in Earth orbit and that the private sector eagerly is awaiting the opportunity to take it over. That’s the rhetoric,” Logsdon said. “The reality isn’t quite that. I don't think there’s a long line of entities that are going to spring into orbital activity once the station is retired.”

American astronaut Joseph Tanner waves to the camera during a space walk as part of the STS-115 mission to the International Space Station, September 2006.

NASA/GettyGone but Not Forgotten

When the International Space Station does wind up operations (which could be sooner than 2031 given that the spacecraft is nearly a quarter-century old, and the fact that Russia hasn’t even signed on past 2024), it will leave a football field-sized hole in the space community and mark the end of an era of cosmo-geopolitical cooperation.

“ISS is the single largest spacecraft ever made—the product of an unprecedented alliance of more than a dozen nations, including the collaboration between two ex-Cold War rivals,” said Dreier. “Nothing else even comes close.”

What will be 30 years of space station research has taught us how the human body responds to weightlessness, the challenges of living and operating technology in space, ways to grow food in harsh environments, and lessons about mental resilience during isolation—all crucial pieces of information for future space exploration.

Experiments on ISS have led to innovations in carbon dioxide removal, robotic surgery, and protein crystal growth for novel cancer drugs and other pharmaceuticals. But its lasting legacy is likely to be more symbolic than scientific.

“My impression is that there has been solid research, but no exciting breakthroughs and that it has existed mainly as a symbol of Russian, U.S., and allied cooperation,” Logsdon said. It offered “a sense of hope and optimism” and was a place from which astronauts could call middle schools and give motivational speeches. (Indeed, one of NASA’s five stated goals for ISS’s final decade is “Inspire mankind.”)

“I think its symbolism of international cooperation is far more long lasting,” Dreier concurred. “Probably the biggest consequence to the space program from ISS will be the creation of this commercial crew and services approach to spaceflight, more than the science.”

But that symbolism still means something, he argued. Case in point: China aims to complete its first space station in low-Earth orbit this year. “It validates the importance of the symbolic value of having a space station,” Dreier said. ”It’s not just some idiosyncratic U.S. idea.”