Memorial Day is upon us, bringing with it visions of summer dancing in our heads, and summer Friday afternoons spent dashing to the beach.

However, think of weekends spent at the beach not actually on the sand soaking up the sun, but holed up inside a massive tower enjoying the chaotic entertainment options on tap.

You’re really living the summer dream when you can roll out of your hotel bed and head right to the bowling alley a few floors down, then enjoy the games and rides of a theme park before heading straight to dinner and a concert without ever leaving the walls of your pleasure palace, right?

It’s hard to believe anyone was ever able to convince a flock of New Yorkers to invest in an idea such as this planned for the Coney Island boardwalk. But in 1906, one Samuel Friede did just that.

Friede had a dream — or rather a scheme — of building a massive amusement park building that would only be dwarfed by the Eiffel Tower.

The Globe Tower, as it was called, would look like a giant steel globe perched on an iron stand and it would contain everything needed to fulfill the every whim and desire of vacationers to the shore (minus the act of actually enjoying the beach, of course).

His plan may have sounded outlandish but it was tried and tested, Friede assured the public. All he needed were people to take advantage of the investment opportunity and buy stock in his company. Once he raised the $1.5 million, get ready for the Coney Island thrill of a lifetime!

At the turn of the 20th century, this proposal seemed almost too audacious to be true. Spoiler alert: it was.

Friede dropped his big announcement on New Yorkers on May 6, 1906 via a full page ad in the New York Tribune, and for the rest of the year he continued to run advertisements in the paper publicizing the opportunity to invest in the company he had formed to make this dream come true, the Friede Globe Tower Co.

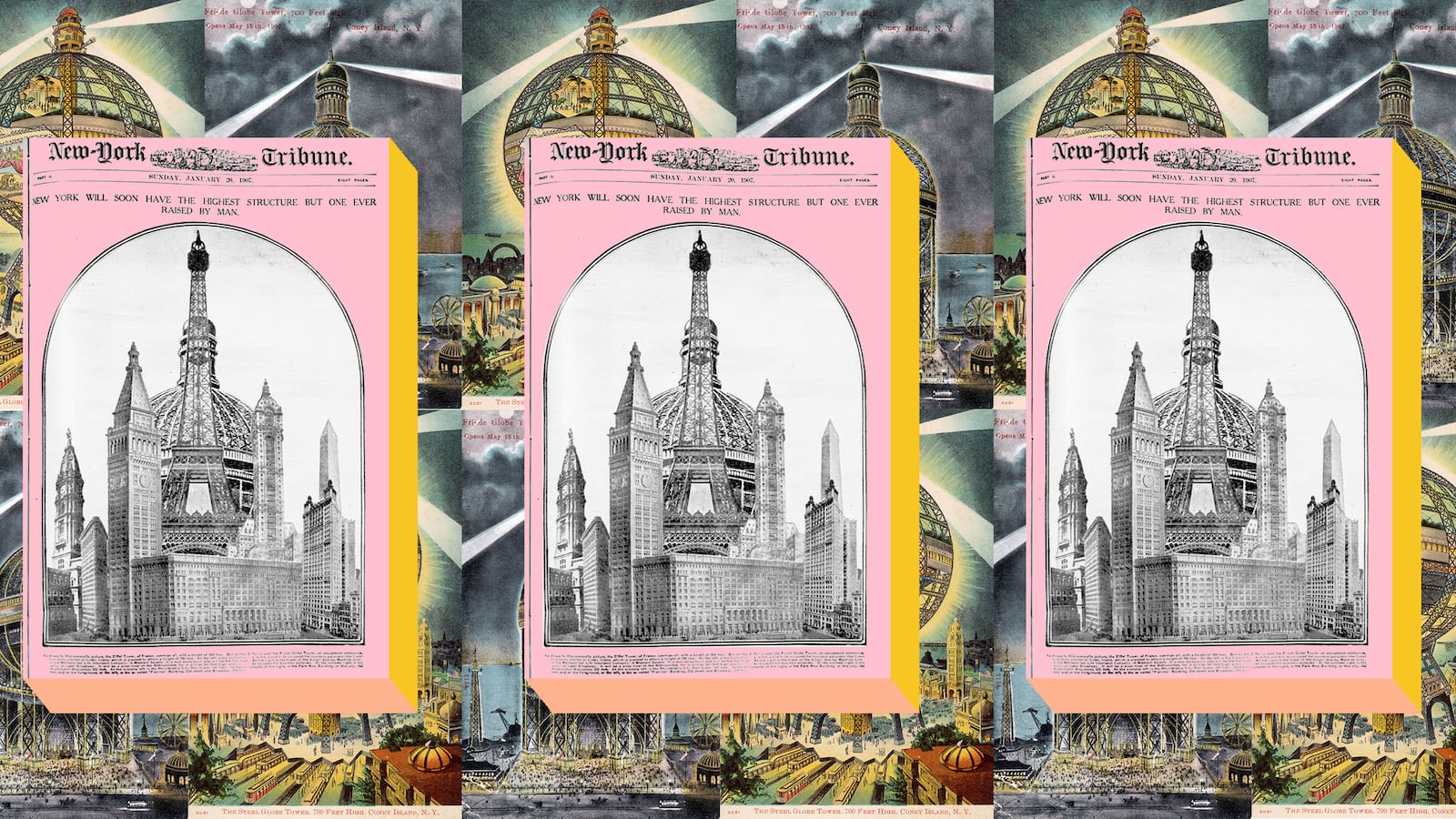

His excitement for the scheme quickly caught on. A flurry of news coverage breathlessly reported on the progress of the tower starting in January 1907. On January 20, a complete takeover of the front page of the New York Tribune announced the upcoming attraction.

“New York Will Soon Have the Highest Structure But One Ever Raised by Man,” the headline proclaimed above an illustrated rendering of all the great buildings, showing only the Eiffel Tower as taller than the massive globe hovering behind it.

Only seven days later, the paper reported that the plot of land Friede had secured from Steeplechase Park owner George C. Tilyou had been cleared and 800 concrete piles were being put into place ready to support “the largest amusement structure in the world.”

The piece went on to say that construction was being expedited — the Friede Globe Tower Co. planned to fully finish this massive project in just a mere few months in order to open for the upcoming summer season.

With the distance of time, the plan is clearly a con. But in the early 1900s, people were more than excited about the prospect of the new attraction. Ten thousand people showed up to the February 17 ceremony attended by government officials and stockholders on the occasion of the laying of the first piece of steel.

“So anxious was the crowd to get a look at the work that much disorder prevailed, and it was necessary to call the reserves of the Coney Island police station,” the New York Tribune reported.

And what was the crowd so excited about?

While an indoor amusement paradise may not be most people’s idea of the perfect summer getaway, Friede’s vision, however outlandish, was impressive.

The Globe Tower was going to be 700 feet high, with the globe portion of the structure 900 feet in diameter. Eleven floors would house 500,000 square feet of space that would include practical considerations — a hotel (with necessarily sound-proofed rooms), a glass-enclosed revolving restaurant, and a roof garden.

Then of course there would be the attractions, which would include a four-ring circus with giant animal cages, a music hall, the largest ballroom in the world, a skating rink, a bowling alley, a mini train, a theater for vaudeville performances, and a smattering of slot machines.

The whole shebang would be topped by a telegraph station and an office and observation post for the United States Weather Bureau.

On March 24, a notice ran in the Tribune that the stock offering was about to close as the project had nearly reached its goal (subtext: if you want in, you need to act quickly). But only six days later, cracks in the foundation of the scheme began to appear.

On May 30, the treasurer of the Friede Globe Tower Co. was convicted to two years and five months in Sing Sing on charges of grand larceny. He had stolen from the company. But the kernel of the real truth was held in his defense that he was only taking money that the company owed him.

Despite this criminal hiccup, the fervor continued for a few more months, with an April 4 article listing the Globe Tower as one of the most anticipated coming attractions at Coney Island that summer.

But news coverage soon slowed to a trickle, as did progress on the actual building site.

By the next year, it was clear the Globe Tower was never going to materialize. Tilyou was left to deal with the pile of abandoned construction materials and scrap metal left on his property, and the courts were left to deal with an investment scheme gone sour. Luckily, they had their friendly sticky-fingered treasurer secured in Sing Sing and ready to turn state’s witness.

The former treasurer, Henry R. Wade, testified that four men who made up the board of the company, including the President Friede, the company’s bookkeeper, the architect of the project, and the Chief Inspector of Elevators at Coney Island (a strategic inclusion), had divided up the company coffers that remained after some of the bills had been paid.

They pocketed $146,000, or $4 million in today’s currency, and this seemed to be just the tip of the iceberg in the lucrative machinations going on at the Friede Global Tower Co.

Later, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported that when the Ponzi scheme began to come to light, the guilty parties tried to cover their financial backs by digging in deeper, creating the Coney Island Hippodrome Company and announcing its latest proposed feat of design, a Hippodrome to serve the tourists of the vacation destination.

A few people invested in the new plan, but it quickly became clear what was going on.

“There is not the slightest chance that the stockholders of the tower company will ever recover a penny of the money which they invested,” read the Brooklyn Daily Eagle on Aug. 14, 1909. As for Friede, he was “finding the climate of Europe more congenial at the present time.”

The denizens of New York had been duped.

Had they looked a little closer at the man with the fantastical plan, the situation might have been avoided.

There isn’t a lot of information about Samuel Friede who, despite his seeming ability at dreaming up wondrous projects, remains eerily silent in most of the coverage of those schemes.

But his attempts to “build” — or at least sell others on his building schemes — left an interesting trail.

Five years before the idea for a grand Globe Tower of Coney Island was announced, the St. Louis Republic reported that a “St. Louis man” named Friede had designed a plan for what he was calling the Friede Aerial Globe to be built for the upcoming World’s Fair in St. Louis.

What was this structure to look like, you may wonder?

Why, a giant steel globe atop an iron stand that would be filled with all the amusements visitors to the fair could dream of.

The specs were slightly smaller than the Coney Island version — it was to be 555 feet tall, have a three-ring circus, two restaurants (one serving only German food, one only American), a rotating cafe, and more with, of course, consideration for the U.S. Weather Bureau at the very top.

This version of Friede’s Famous Invisible Globe (as it should have been called), planned to have two glass-enclosed iron walkways that circled the outside of the massive dome to provide the best — and assuredly most terrifying — view for visitors to the Fair.

“This is the age of steel. The Friede Aerial Globe will represent the extreme possibilities of steel structural work. Originality of conception is united with strength and simplicity in construction,” reported a December 22, 1901 piece. “The dream of the designer, before the first step could be undertaken, was subjected to the cold scrutiny of scientific investigation, and the massive plans have been ‘worked out’ to the last bolt.”

While Friede had proposed this building for the World’s Fair, he assured it would be a permanent structure that would entertain St. Louisans for years to come. Of course, he was willing to give them the opportunity to profit off of their city’s latest wonder by purchasing stock in the project, as the newspaper ads he placed proclaimed.

You will no longer be surprised to discover that this scheme never came to fruition. The Fair opened with spectacular exhibitions to be seen and new buildings to be observed, but the Friede Aerial Globe was not among them.

This didn’t stop Friede. In July of 1904, he popped up again, this time being described as a “Chicago inventor” who was peddling what the Western Kansas World called “a freak resort” for the site where the Ferris wheel built for the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair once stood. Friede was proposing to build a giant globe on an iron stand…you get the drill.

The references to the Chicago scheme are glancing. It appears he quickly moved on and found a much more receptive — and gullible — population two years later in the New York crowd.

His con was no doubt devastating to many at the time. But today, Coney Island beachgoers can look up to the sun and give thanks that their long summer days spent in tanning heaven aren’t being overshadowed by a giant indoor amusement park in the sky.