When my godson Trey was a toddler growing up in Brooklyn, every white woman who saw him fell in love with him. He was a beautiful child, sweet natured, affectionate, with cocoa-colored skin and a thousand-watt smile. I remember sitting with him and his mom in a pizzeria one day, watching as he played peekaboo with two white ladies at a nearby booth. “What a little doll!” the ladies cooed. “Isn’t he adorable?”

I told Marilyn I dreaded the day he would run up against some white person’s prejudice.“His feelings are going to be hurt,” I said. “He won’t know it’s about this country’s race history, he’ll think it’s about him. Because so far in his young life every white person he’s ever met has adored him.” Marilyn nodded, but her closed expression seemed to say I was talking about things I didn’t really understand.

She and I had been a part of each other’s lives for three years then. We’d met at Brooklyn College, fall semester, 1989. A couple of weeks before school started, a black teenager and three friends had been surrounded by a mob of 30 bat-wielding white kids in the Brooklyn neighborhood of Bensonhurst. One of the white kids pulled a gun and shot 16-year-oldYusef Hawkins dead. The Reverend Al Sharpton was then leading marches through Bensonhurst, where whites lined the streets, hoisting watermelons over their heads, shouting Go home, niggers! as the black marchers pressed forward, arms linked, chanting No Justice No Peace! The media was in a feeding frenzy. You couldn’t escape that racially charged story anywhere.

My students’ papers that semester, and their conversations, centered heavily on race. One of my classes—the one Marilyn was in—was made up almost entirely of young people of color. My other class was mostly white students, many of them from Bensonhurst. The white youngsters knew with absolute certainty that the killing of Yusef Hawkins was never about race. It was about territory, they said. Those white kids in Bensonhurst weren’t racists, they had black friends, even. They’d thought the black guys were in their neighborhood to beat up white kids, and anyway, the shooter was a lone wolf, a crazy kid, he didn’t represent the real people in Bensonhurst, so why did that loudmouth Al Sharpton have to invade their neighborhood and stir everything up?

But the African-American and West Indian students saw things with different eyes. I read it in their papers describing the thousand daily cuts and fears and indignities. They knew, with equal certainty, that Yusef Hawkins died because of the color of his skin. In those months I understood for the first time what should have been obvious but wasn’t—at least not to me, growing up when I did, where I did, the 1960s in Oklahoma, on the white side of town. In this country, the witness we bear the world, how we see, what we see, isn’t determined by facts or objectivity but by the color of our own skin.

Marilyn was one of those West Indian students, a beautiful Jamaican girl, just 18, shy and scared, because she’d just found out she was going to have a baby and she didn’t want to tell her mother. She confided in me, and I talked with her, told her she was going to need to tell her mother, that was all. Towards the end of the semester she called me up and asked if I would be godmother to her child, and I said yes, and Marilyn and her family have been my family ever since. A quarter of a century now. The night I went to her baby shower at her mother’s apartment was the first time I was ever inside a black home. I remember leaving my white neighborhood, driving deeper and deeper into the interior of Brooklyn until I reached unfamiliar streets, where every passerby, every car occupant was black. I remember climbing their apartment house stairs with an overly friendly smile on my face. I remember the brightness of the kitchen, the spicy smells of cooking, the formality with which Marilyn’s mother welcomed me and led me to the living room, offered me a drink. I remember how out of place I felt, sipping my drink alone on the couch while the getting-ready activities swirled around me.

As other guests arrived, the living room began to fill with the rippling sound of patois gliding over the stutter of steel drums, the syncopated monotony of reggae rhythm. They were mostly women—relatives, family friends, a couple of Marilyn’s girlfriends from high school—but there were men too, her brothers and their friends passing through the living room in their high-top fade haircuts or Jheri curls and Kangol caps, stopping by the kitchen to pick up a Heineken or a wine cooler, to load up their plates from the mountains of food. Marilyn arrived very late, for the surprise party that was clearly not much of a surprise. She sat beneath a crepe paper parasol, smiling self-consciously from time to time at all the attention, but she said very little, her face calm, serene. She looked at me and smiled. I felt it then, that acceptance. To Marilyn I belonged there, in her home, along with all her other family and friends.

***

Trey was born on a cold February morning the same week Nelson Mandela walked out of a South African prison after 26 years. New York’s first black mayor, David Dinkins, elected in the aftermath of the Yusef Hawkins killing, had been in office six weeks. A Haitian woman had recently been beaten by a Korean store clerk on Church Avenue in Brooklyn, or she’d fallen down shrieking, pretending to be beaten, when the clerk accused her of shoplifting. Two different versions.The boycott of Korean grocers by the black community in the West Indian district was in full sway.

As for my godson, I completely adored him—just like every other white lady who ever saw him. Weekly I’d drive across the borough to pick him up to come stay the night. In Marilyn’s neighborhood I had to park far from their door and walk several blocks with Trey in my arms, and along those blocks there would be many people, all of them black. They glanced at us with curiosity, but they didn’t stare. Still, the exposed skin on my face and hands felt drawn and hot, stinging, a fire of whiteness, a burning Caucasian husk.

Inside their apartment I didn’t feel that way. Inside, there was no color difference between us, in the same way there was no difference between Trey and my husband and me when he came to stay the night—except on the street when a white passerby, usually female, would glance casually from my face to the baby’s. At once she’d dash a quick bright smile across her face, a smile that said something like oh, pardon me, I didn’t mean to stare…well, my, aren’t you just the cutest thing?

I’d push Trey in his stroller to the park, where I would be the only white woman with a black child, though there would usually be several black women with white children—nannies, caretakers, who eyed me, I thought, with resentment, suspicion. What’s this white lady doing with this precious black child? Or so my acute race consciousness told me. The city roiled with place names signifying race trouble: Bensonhurst, Howard Beach, the Central Park Jogger, Crown Heights. Every racial incident felt acute and personal to me. Complicated. Unresolvable. Guilt-filled.

When Trey was 2, the L.A. riots broke out. I longed to drive across town to be with him and Marilyn and their family. I wanted to say to them in an erupting world: It’s not me. Not us. But I had a fever, some kind of viral infection, and I was too sick to go. Through four wrenching days and nights I watched the news, the fires raging, the images of people running, a white man being pulled from his truck by black rioters and beaten, the talking heads giving their fatuous interpretations, the sad, helpless moment when Rodney King stood in front of all those microphones, saying, “Can’t we just get along?” I watched again and again the videotape of the white cops standing over the struggling black man on the pavement, beating him mercilessly, the image repeated in endless news loops.

As Trey grew older, his hunger for a father seemed to be the driving force of his young life. He was 5 when Marilyn met Erick, a recent immigrant from Jamaica, a good man, a hard worker, crazy about her, and—just as important—crazy about her son. A year later she married him. Erick became the father Trey needed. He raised Trey as his own.

By the time our boy was an adolescent, big for his age, very grown looking though he was still just a kid, I understood too well what Marilyn’s expression had meant that day in the pizzeria. Of course it wasn’t middle-aged, middle-class white women giving him grief. It was the white security guard at his school, for instance, who found Trey wearing his cap indoors one day in violation of school rules. The guard tried to confiscate it, but Trey resisted—that Yankees cap was a gift from Erick, he was afraid he wouldn’t get it back if the guard took it, and so Trey held on.

The guard grabbed him in a headlock, clamping his arm around my godson’s throat, choking him, and Trey, unable to breathe, grabbed hold of the man’s arm, trying to break free. The guard shoved him against the wall, jerked his hands behind him and handcuffed him. Then he took Trey, not to the principal’s office for wearing a ball cap in school, but downtown to Brooklyn Central Booking, where my godson was charged with assaulting a school security officer. Trey was 14 years old.

When he was old enough to drive, Marilyn and Erick bought him a car. They were doing well by then, both advancing in their careers; they owned a home near the Belt Parkway, had two beautiful daughters in addition to Trey. A growing, happy middle-class family. Every afternoon when Trey left school in his car, two white patrolmen would follow him in their cruiser, sometimes a few blocks, sometimes several miles, before turning on their patrol lights. They’d make him get out while they searched the car, after asking his permission, which Trey always gave, in part because he knew he had nothing to hide, in part because he was afraid of what would happen if he refused.

The officers never found anything to arrest him for, but they kept trying, because they seemed to think a black teenager would not be driving a late model car unless he was a drug dealer. After the search they’d issue a ticket for whatever excuse they’d used to stop him: failure to keep right, failure to use a turn signal. Garbage tickets, Marilyn called them as she wrote out the checks to pay the fines.

At 17 Trey was arrested for petit larceny—accessory lights stripped off a vehicle by a couple of black youths who matched Trey’s description. Matched, in fact, the description of hundreds of young black men in Brooklyn: braids, dark baseball cap, saggy jeans. The police homed in on my godson because of all those tickets; they put him in a lineup with four grown men over 30, Trey the only teenager with braids in the room. Of course he was the one the complainant picked out.

The arrest cost my godson a night in jail, cost his parents thousands of dollars in attorney fees, even though we all knew he didn’t do it—and not just because we know Trey is no thief. He was in the dentist’s office at the very time and date written on the complaint. Marilyn was with him. She told that to the white detective at the precinct.

“Sure, lady,” the detective said. “Take it up with the judge.”

After court appearances that dragged on for a year, Trey finally pleaded guilty to a crime he didn’t commit in order to guarantee he wouldn’t have a record. That was the deal the lawyer worked out: a plea of guilty in exchange for the record being expunged if Trey stayed out of trouble. I want to tell you something: it is nearly impossible for a young black man to stay out of trouble in a country where skin color is the marker for suspicion and violence and grief.

I want to tell you about seeing my godson handcuffed and put in a holding cage with other young black men at a Brooklyn precinct for driving while black. I want to tell you about sitting with Marilyn and Erick in a Brooklyn courtroom in a sea of black and brown parents while their sons are brought before the judge. I want to tell you about what stop-and-frisk does to a young man’s soul, tell you about a judicial system that is far less about justice than it is about arrest numbers and fines and plea bargains that parents agree to in hopes of keeping our sons out of jail.

Trey is grown now, in college, the father of a little girl. The police still stop him on the street, search him, search his car. He knows to stand absolutely still, keep his hands where the cops can see them, be cooperative, polite.

These days Trey isn’t the one who comes upstate to visit but his younger sisters, Rosie and Grace, my goddaughters, 14 and 9 now, beautiful, smart, funny, laughing girls. We always get them for the Fourth of July, our annual tradition. This past summer, though, Marilyn had to delay our plans. I could tell from her emails there was something going on. She was distracted, busy at work, she said, but I sensed it was more than that. Still, I thought it couldn’t be anything too troublesome or she would have called to talk. Finally we set the date for me to come pick up the girls. Marilyn told me she wouldn’t be going to work that day, she had something she had to do. “What’s going on?” I asked her.

“I’ll tell you this evening,” she said.“I don’t want to talk about it on the phone.”

Marilyn was upstairs when I got there. Erick was in the kitchen with the girls, getting ready to leave for his softball game. He plays in a summer league, is a terrific player, always wins trophies, and usually when he heads out to a game, he’s joking, high spirited, teasing his daughters. This evening, though, he was very quiet. I could sense a kind of, I don’t know…a darkness in him. A weight I’d never seen before. Marilyn, too, when she came downstairs, was more silent than usual. They had that air of grownups trying to make things seem normal in front of the kids. Trey wasn’t around. The girls, for their part, seemed fine, though, their normal happy selves.

I had a tight feeling in my chest, a cold sense of dread. “Where’s Trey?” I said, half afraid to ask. “Oh, he’s at school,” Marilyn said. “He has a night class.” Okay. If not Trey, then who? What? I remembered then that Erick’s younger brother was visiting from Jamaica. I was afraid it might have to do with him, because Erick was the one enveloped in a dark cloud.

After he left, Marilyn sent the girls upstairs so we could talk. She went to a closet and brought out a brown paper bag stuffed with clothing; she sat across from me, pulled out different items, spread them formally on the living room floor: a man’s dark vest, ripped into two pieces, a red shirt, torn and blood-stained, torn men’s khaki trousers, also blood-stained. She laid out a woman’s dressy outfit, too, a summery short skirt and pretty blouse—her own clothes—but it was the blood-stained man’s shirt and trousers that caused my heart to catch. The shiny black vest ripped into two pieces. Inert evidence of violence, eloquent, silent.

“It was a beautiful night,” Marilyn began. “A holiday weekend. Me and Erick just sitting home, relaxing. Trey and his girlfriend went out, and around midnight he called…”

Trey told her it was a fine night at the nightclub where they’d gone to celebrate the beginning of summer: good Jamaican food, good music; some of their friends were there. He wanted Marilyn and Erick to come out. So they dressed up nice and drove over to Flatbush. They’d just got settled at a table and ordered a drink when the overhead lights came on, the music stopped, and everybody was ordered to leave.

Once they got outside they saw a man lying on the sidewalk, people milling around the front of the club saying he’d been shot; there were sirens, a lot of turmoil. No one wants to be around a shooting, Marilyn said, an investigation, police trouble. Trey and his girlfriend hurried to his car parked on the street and left. Marilyn and Erick walked quickly to the club lot where they’d parked their Mercedes. They passed a woman lying on the sidewalk near the entrance to the parking lot. They hurried on, got in the Mercedes, and Erick started to pull out, had moved maybe half a car length when they heard a voice yelling. Stop! Get out of the car!

It took them a second to realize it was the police, and that they were yelling at them. Erick stopped, put the car in park, rolled down the window to find out what they wanted, but the voice was still yelling Get out of the car! Get out of the car! “OK, man,” Erick said. “Hold on, give me a second.” He started to glide the window back up to get out of the car, and at once the officer began to beat his gun butt on the window. Get out of the car! Get out of the car!

Before Erick could open the door, the cop smashed the window, glass shattering all over the front seat, and he reached in, jerked open the door, dragged Erick out onto the ground. By then other policemen were swarming, a female officer was on the passenger side telling Marilyn to get out of the car. The first cop had Erick handcuffed already. He wrenched him up off the pavement and shoved him against the Mercedes, and Erick stumbled, off-balance with his hands cuffed behind him, and the police officers, all together and at once, piled on Erick and began to beat him.

“They beat him and beat him,” Marilyn said. “They take him between two cars so nobody can see and they beat my husband and I can’t do anything. The woman cop was there beside me by my side of the car, I’m yelling, ‘What are you doing? You just going to kill him for no reason?’ They have their guns drawn, they’re beating him with batons, their flashlights, it’s dark, there are so many cops on him, and I’m just watching my husband get beaten, I can’t do anything. His hands are cuffed behind him, his head over a guardrail, they’re beating their batons and flashlights all over his back, his legs, his head, I can hear the grunts and thuds, hear those batons smashing down on the steel guardrail, and it just goes on and on and on. Nobody stopping them. Nobody to stop them. They beat my husband till his pants are down to his knees, they rip his clothes.” She touched the two halves of the vest. “His belt broke, they tore off the chain around his throat where he keeps his wedding ring. That ring just lost now, we’ll never find it. They beat his head horribly, but they don’t beat his face. They don’t want anyone to see it. I finally think to cry out, ‘I hope somebody videoing this! Somebody video this! You see what they’re doing!’ That, finally, is when the beating stop. That is the only thing that stop them. I think now if I didn’t yell that, maybe they really would have killed my husband.”

She paused. I stared at the torn clothing. When Marilyn went on, her voice was low and quiet. “I’m just glad Trey left already. I think if he was there he would have jumped in. I know they would have killed him.” She looked at me. “Isn’t that something? The one thing I have to be grateful for is my son wasn’t there to see his father beat like that, because otherwise I think he would be dead. They would maybe both be.”

Listening, my throat tight, my heart racing, I felt a dark fire in my chest, familiar to me now after all these years: hatred and outrage, and fury. I was crying, too, more or less, a dry weeping that stopped at my throat, my anger so great I couldn’t make any tears. When I was able to speak finally, I didn’t need to ask why—why would the police do that to a man like Erick, a hard-working family man, a loving father, law-abiding citizen who has never in his life been arrested, never once lifted a violent hand to anyone. I asked only, “How many were there?”

“I don’t know,” Marilyn said. “Maybe seven or eight doing the beating. Others all over the parking area, the woman cop by me.”

“Were they all white?”

“The ones that was beating him, yes.”

“Why didn’t you tell me?” The beating had happened in late May. This was August. They had been dealing with the aftermath all summer. “I don’t know,” she said. “You were in Oklahoma when it happened. They had those tornados down there, you had your family to think about. I didn’t want to worry you…” She grew quiet, shook her head. “I didn’t want to talk about it on the phone.” We sat in silence a while. I could hear the girls giggling upstairs, their TV music shows going. In a few minutes Marilyn went on to tell me the rest of the story:

She and Erick were both arrested, put in the back of a cruiser with their hands cuffed, taken down to Brooklyn Central Booking, locked up in holding cells. “You cannot believe how filthy that place is,” she told me. “How disgusting. How terrible it smells.” Marilyn’s face, when she told me this part, held all the layers of pain and indignity. I could see what it had cost her, being put in that degrading place. They charged her with two misdemeanors, Obstructing Government Administration, Failure to Obey Police Officer. She asked for a desk appearance ticket, a summons, so she could go home to her children, but the officer said no, she had to wait and see the judge.

And so my godson’s mother, a successful professional woman, a kind and graceful, law-abiding person, sat in a filthy cell in Central Booking all night and all day and most of the next night. In the end they released her after 1:00 a.m. onto the dark streets of downtown Brooklyn, alone, with no money, no purse, no phone, no way to go home or to call anyone to come get her. No way to know what they’d done with her husband.

Erick, horribly beaten as he was, they held for two days. They’d given him a Breathalyzer test as soon as they brought him in, and when it came back negative, they drove him to a second location for a more detailed drug test. They wanted him to be drunk or on drugs. They needed a reason, a justification. They knew they’d made a mistake. They charged him with reckless endangerment, resisting arrest, a long list of charges.

The officer who handled the paperwork came in to talk to him: “You know I didn’t have anything to do with this, right?” he said. Meaning the beating. He told Erick he shouldn’t go to the hospital now, not from the precinct, it would just make everything take longer. “Wait to get released,” the cop said, “and then go for medical attention if you need it.”

And Erick did need medical care. He went to the emergency room three times over the next few weeks. The headaches wouldn’t stop. His hand was numb, he couldn’t feel his thumb; he could move it but couldn’t feel it. Every time he breathed, he felt pains all through his torso—fractured ribs. When he went to the hospital the first time, on the day he was finally released, the attending physician asked him what happened to him. He told her. She said he should file a report. She called the precinct, and they said they would send someone to take Erick’s statement. He waited at the hospital for hours. No one from the precinct came. The physician had to go off duty. I’m sorry, she told him. Erick nodded, said thanks for trying, and he drove himself home in his car with its busted window.

Meanwhile Marilyn called friends and family until she found a lawyer; she took thousands of dollars from savings to pay his retainer and the bond he arranged to get Erick out of jail. Thousands more for him to represent Erick to get the felony charges against him reduced. Not to defend him. Not to say this man is innocent, but to arrange for a plea deal. If Erick was convicted of a felony, he could go to jail; he could lose his job, his means of supporting his family.

In the living room that night Marilyn told me his court date had been that very morning. This was why she’d taken the day off from work. Erick was furious in that courtroom, she said. She’d been afraid for him, what the anger might do. “Where’s all the white kids?” he’d kept saying. “Don’t any white kids commit crimes in Brooklyn?” Every defendant was black or Latino. The only whites in the room were people who worked there, lawyers, clerks, district attorneys, judges.

As the lawyer had arranged, Erick pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor charge of disorderly conduct and received a sentence of three days of community service and court costs. The charges against Marilyn had been dropped. This was the source of the dark weight I’d seen when I came in the kitchen: Erick’s anger, frustration, outrage, all held tightly contained inside him, along with the overwhelming sense of the injustice, and his own powerlessness in the face of it.

He felt he’d had no choice. The arrests had already cost them ten thousand dollars for lawyer’s fees, bail, medical bills, repairs to his car. They didn’t have the thousands more it would cost to go to trial and claim his innocence. And if they did go to trial, as the lawyer pointed out, there was no guarantee Erick wouldn’t be convicted. It would be Erick’s word against the word of the police. The lawyer had tried to get the videotape from the parking lot security camera showing the beating, but the police had already confiscated it by the time he went to the club to ask.

And so, just like Trey before him, Erick pled guilty to a crime he didn’t commit. Erick is a master technician for a cable company. Marilyn is an associate dean for a major university in Manhattan. Neither had ever been in any trouble with police, never had so much as a driving ticket. There was no reason this should have happened to them. Except it did.

Later, I asked to see their arrest reports. The list of charges against Erick runs from worst to least, felony to misdemeanor to violation to infraction: Reckless Endangerment, Obstructing Governmental Administration, Obstructing Emergency Medical Services, Resisting Arrest, Reckless Driving, Fighting/Violent Behavior, Failure to Obey Police Officer.

Failure to Obey Police Officer. The last one on the list. A mere infraction. This was Erick’s real crime. He is a black man who failed to obey a police officer. He’d made the mistake of starting to roll up his car window before opening the door to get out. That’s when the officer smashed the window, dragged Erick out and handcuffed him and began to beat him, and the others jumped on him to beat him, seven or eight white officers on one black man.

If you don’t think this is the reason, then ask yourself this: what well-dressed 42-year-old white man driving a Mercedes would be dragged from his car and beaten the way Erick was beaten for starting to roll up his car window?

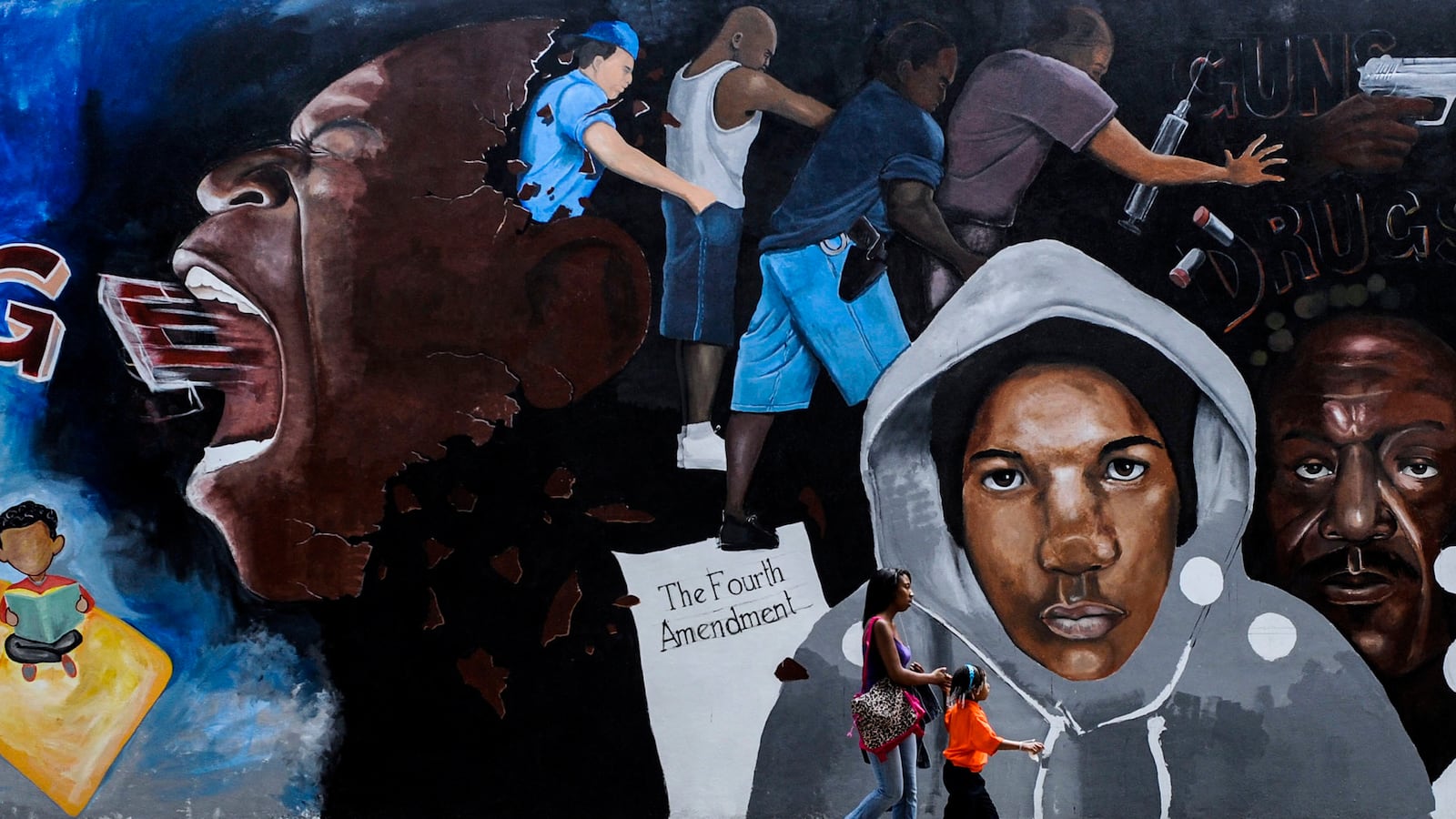

I see my godson’s smile like honeyed lightning when he was a little boy, and I see him as a teenager in braids and handcuffs inside a steel cage in the lobby of a Brooklyn precinct, where they held him for hours before taking him downtown to book him for a crime he did not commit. I see my godson’s father teasing his giggling daughters, leaving for his ball games, coming home tired from work. I see him struggling on the ground, powerless, his hands cuffed behind him, trying to avoid the blows from police batons, and Marilyn crying out from the other side of their car, helpless, and the beating going on and on and on. Not in 1963 in the old slave-holding South, not in 1991 in a ghetto in Los Angeles, but in 2013, in a dark parking lot in Brooklyn.

Marilyn and Erick had gone out for a casual evening to celebrate the start of summer and got caught in a nightmare—for what reason? Like the students in one of my classes at Brooklyn College years ago, I know the answer very well. Know it truthfully, to the bones of my being, know it from being a part of Marilyn’s family for twenty-five years. There’s the weight of American history, the effects of policing programs that give officers a sense of impunity; there are a dozen complex and complicating forces that come down to one thing: the reason this happened to people I love is because of the color of their skin.