Patrick Brice and Mark Duplass’ 2014 two-hander Creep was inspired by a variety of sources: found footage horror cinema; their shared passion for, and obsession with, oddball human behavior; and Duplass’ personal experiences with the lonely hearts of Craigslist’s clientele, among others. Similarities between the film’s plot and the gruesome exploits of Philip Markoff, best remembered by popular culture as “the Craigslist Killer,” are coincidental. As authors, Brice and Duplass take a far greater interest in real life as they see it, rather than as it’s documented in headlines.

Now Brice and Duplass are revisiting the film and its 2017 sequel with The Creep Tapes, a limited series adaptation of the franchise, which premiered Friday on AMC, backed by Shudder. The original films functioned as sandboxes for the pair, where they were able to dig deep into behavioral dynamics through a lens of anecdotal Craigslist interactions gone south; tension is stirred by awkward interactions between Duplass’ character, an anonymous serial killer, and his victims-to-be: Brice in Creep, and Desiree Akhavan in Creep 2.

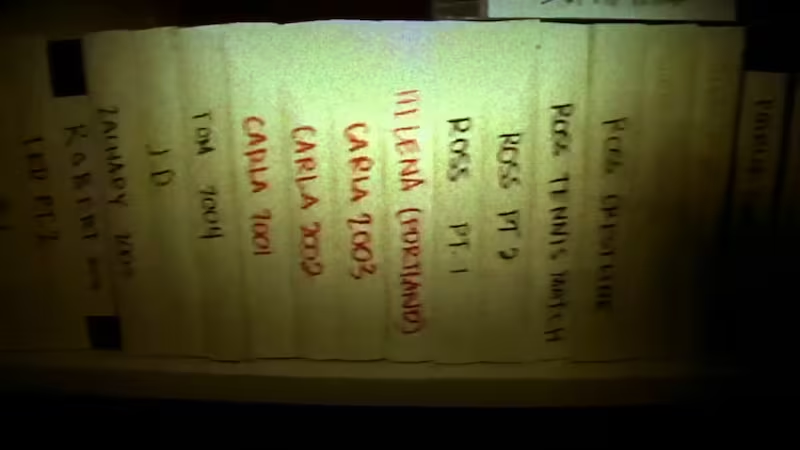

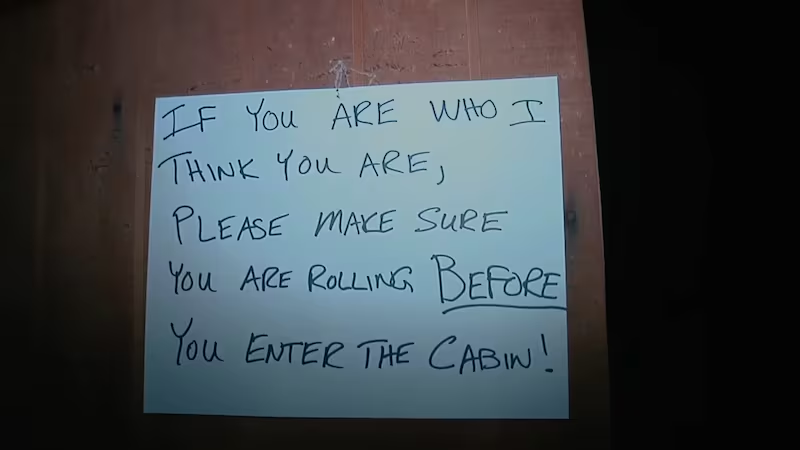

The conceit is simple: In both films, Duplass’ charming psychopath lures unsuspecting videographers to his cabin through Craigslist ads; he plays psychological mind games with them before swinging an ax in their faces, then tucking away the tape recording of the incident in his VHS collection (of murders).

The Creep Tapes largely sticks to that formula, with a few tweaks. “Mike,” for instance, the series opener, stays true to Creep’s mode in terms of setting and structure, while other episodes leave the woods behind for new environments. Some of them even take place under daylight—and they’re still unnerving to watch, a testament to how well Duplass and Brice know this character and his methods, as well as what makes viewers squirm in horror’s contemporary golden age.

With The Creep Tapes having premiered on AMC Friday, we chatted with Brice and Duplass about the liberties afforded to them in translating the movies to television:

Creep came out in 2014. Creep 2 was 2017. Movies and shows don’t really get to choose their moments, but at the same time, I’m curious if there are traits inherent to 2024 that make it a moment that’s well suited for Creep as a TV series?

Brice: Yeah, I mean, you’re absolutely right. They don’t get to choose their moments, nor do they get to choose the life that they take on. One of the delights of my career and my professional life has been seeing this thing that Mark and I made, that really came from this intimate, purely creative, purely joyful experience, take on a life of its own and become this cult film; even making a sequel was beyond our wildest dreams, when we were conceiving the first movie. So making a sequel, and then finding ourselves able to feel free and have a sense of play that was even greater than the first movie, because it came with a lot more intention that time, made it so it was something that we always wanted to revisit.

It feels like the fan base has only grown and grown since then with these movies, and that’s another thing that we’ve been surprised and delighted by. The demand for it has also been something that’s been really surprising for us. Mark can’t post anything on social media without someone demanding, “Where’s Creep 3?”, you know?

And now they get The Creep Tapes.

Brice: So we always wanted to do it, but the issue was time, and the issue was, “What are we gonna do? What are we gonna make?”, you know? For a long time we were thinking of Creep 3, and coming up with different scenarios and different ideas. We had probably eight or 10 ideas for what a potential Creep 3 could be, but we were still feeling the pressure of a third movie, and wanting to get it right. It was actually Mark who called me one day with this epiphany of the tapes, and that blew our minds as a way to go in and make Creep as a shortform series, fit it into our professional and family life as something that we could go shoot very quickly and make very quickly, and make these mini versions of the movies, essentially. We, unbeknownst to ourselves, created this great conceit of these tapes hiding in this character’s closet, so of course there’s gonna be this curiosity about what’s on them. I want to see what’s on them. I wanna see what goes on there.

For us, it unlocked a million possibilities to find our joy, and play not only with different tones, but also different characters and obviously different actors. It was a real treat for us. It’s been a surprise.

Duplass: One thing I would add to that, too, that has allowed us to do what we want when we want is this—I hesitate to call it a franchise, because that really sounds like I’m talking about like something Marvel or DC, but it’s two movies in a series, so I guess it is kind of like a little mini franchise. Patrick and I own this because we made the first movie on our own, and we made this entire series completely on our own, independently, over the course of a year. Then we took it out to the market and found this incredible partner in Shudder and AMC. So we try to, as much as possible, keep ourselves in the driver’s seat so that we can do whatever we want and whenever we want so we can follow our creative bliss.

Watching the episodes, I got the sense of additional culpability as the viewer, because now, I feel like I’m flipping through Josef’s, or Aaron’s, or whatever [the killer’s] real name is, tape collection personally. Was that part of your idea, making the viewer feel like they’re the one picking out each incident that they’re going to watch?

Duplass: It wasn’t my idea, and this is pivotal to the process. My only idea was: There are the tapes, let me call Patrick, before I even had anything, any ideas. This is how it happens. Then we called Chris [Donlon], who’s our third collaborator in this. He’s our editor, he’s with us on set, he’s helping us with the story along the way and everything. So it really is like three kids in the woods with a little video camera trying to figure out what’s next, and it’s purposefully done that way, because I think that spirit is very evident in the show itself; there’s a lot of “act first, think later.”

That’s very true.

Duplass: And that doesn’t mean it’s not extremely taxing and extremely difficult while we’re out there, because we’re piecing together this narrative as we shoot. The way these things happen, because there are no traditional cut points, you have to get most of these scenes done in a oner. That means it has to be paced correctly. So we’re writing the script as we go, we’re rehearsing the script, we’re cutting down the script as we go. So it’s quite a painstaking process, but that initial kernel of grabbing an idea and going immediately, before you beat it to death with your brain, has been the cornerstone of what we do here.

To hear you describe your process, it reflects the process by which he kills people. All he’s doing is improvising. I hate to be cliché, but it almost feels like he’s playing jazz.

Duplass: That’s what it is. He’s thinking, “Hey, I’ve got this guy. I think we’re in the key of B minor here, we’re 130 beats per minute. We’ll leave some space for a little bit of an indulgent solo in the middle, but before it gets too indulgent, I’m going to get us back on track with a melody.” [Laughs.] It’s all very much a jazz standard, yeah.

You talk about [the process] being taxing. I wonder if the winnowed down structure of each episode, and if having a different setup in each one, either adds to or alleviates that? The setup of the first episode is classic to the films, but “Elliot” is something else. So I’m curious about the push-pull between the creative fun of having different setups, but also having to come up with new setups for each tape. I feel like that might be taxing, too.

Brice: Yeah, it’s very taxing. And not only that, the found footage form, while it provides limitless possibilities in terms of what we’re seeing and what the characters are shooting and everything, it also creates this ultimate constraint of “why is the camera on” from moment to moment, when we’re watching this. So there’s constantly that question that we’re having to ask ourselves whenever we come up with any of these crazy ideas. But it’s also very freeing at the same time, not only just thinking about what we’re doing in the actual episode, but also like where our reference points are coming from.

The “Elliot” episode is actually one of my favorites, and that was partly because I was thinking about Gus Van Sant’s Gerry, and Matt Damon and Casey Affleck. [Laughs.] We’re just watching these two guys get lost in the desert for an hour and a half. So the idea of planting Mark’s character in a desolate landscape, in this case central California, with one other person, and how scary it would be to be in that space with one other person, was really exciting to me—to get us out of the cabin essentially, which we’ve been using, and will continue to use for a lot of these, and to show him in a different space, in a different landscape.

On the other side of that creative freedom, is it difficult to streamline the concept of the movies into 20 to 30 minute episodes? We get to know your [Patrick’s] character in the first Creep, and Desiree Akhavan’s character in the second. Because there’s less space in the episodes, we don’t have time to develop that same relationship with Mike, with Elliot, with Jeremy, etc. What concerns did you guys have in regards to what you might lose in that process?

Duplass: Yeah, there were a lot of gains and losses that we had ideas about, and as usual preconceptions, they turned out to be just that. You never really know what you’re going to get out of these episodes because of the way they’re structured, and because of the way that they’re planned. I think for us, being open to whatever can happen in the moment is the clutch for this, right? What we’ve discovered so far is that some of these are going to be a lot funnier than we thought they would be, and some of them are going to be a lot scarier than we thought they would be. We’re open to however people want to take them. When we show these episodes to people and they’re at home alone watching it, they’re terrified; when we show them in a movie theater, a hundred people are laughing their asses off and having a great time, and they still get their jumps and scares.

The point of what I’m trying to say is, we have surrendered the fact that we might be in control, tonally, of exactly how an audience is going to receive these. We just go for whatever tickles our fancy in the moment. I think what did happen with these episodes is, they play much faster, and it opens us up to a wider audience who weren’t necessarily game to go with that incredibly slow, tense pacing of the features. But we also want to make sure we leave room in each episode to have one of those five or six minute incredibly slow, strange scenes play out, because that’s[the films’] bread and butter.

We definitely see that.

Duplass: So yeah, there’s losses and gains, but ultimately I think I prefer making the show and the episodes, because we get together in a different place with a different actor three or four days at a time in between Patrick directing a movie, or me being on The Morning Show. It’s this way to connect to our childlike creativity in little bursts throughout the year, and it feels like that’s really sustainable and that we can continue to do this.

Patrick said something funny the other night: “This franchise is like our version of Boyhood.” So we’re going to watch me get really old and just kill people while I do it. [Laughs.]