Palulu.

All you had to do was say the name and José Miguel Battle Sr., the Godfather of the Corporation, would tighten up. He would breathe in deeply, his ears would turn red, and his blood pressure would rise to levels that were clinically unhealthy for a man of his girth. Palulu was the stone in his shoe, the thorn in his side. If one of Battle’s men mentioned the name of Palulu in his presence, he would find himself on the receiving end of a stare so chilling, so filled with bad intent that his gonads would inadvertently shrivel up in his scrotum.

It had been eight years since El Padrino first called for Palulu’s head. Now the mere fact of Palulu’s existence was, in Battle’s mind, a rebuke to his manhood. If someone had put Fidel Castro and Palulu in front of him and said to kill whomever you must, Battle would first have to kill Palulu and then go after Fidel. Palulu had killed his brother in a very public way. Palulu had pissed on his family’s name. Palulu, who by now had already survived half a dozen attempts on his life, just by the fact that he breathed the same air as José Miguel was an abomination. Palulu was making José Miguel Battle and the Corporation look foolish. This was a problem that had to be dealt with—pronto. Or Battle might as well retire to his finca in South Miami and spend the rest of his days stroking his rooster.

On April 30, 1982, Palulu Enriquez walked out of Dannemora prison after having served two years and five months for illegal possession of a weapon. From the moment he hit the streets, he must have felt like violating the terms of his release by doing the very thing that got him incarcerated. A gun was certainly what he needed. He knew there was a bounty on his head.

And yet, like a creature of habit, he returned to the streets of New York.

Throughout his legal troubles, Palulu maintained ownership of a condominium at 3240 Riverdale Avenue, in an upper-middle-class section of the Bronx. Riverdale was a pleasant neighborhood, mostly Jewish, with tree-lined streets. Over the years, Palulu had rented out the condo and lived off the proceeds. Ever since he had fallen afoul of the Battles, he had resided mostly in small one-room studios spread out around the boroughs of New York.

In December, eight months after his release from Dannemora, Palulu was limping along a street in Brooklyn, where he now lived. For a man who had lost a leg, suffered multiple gunshot wounds, and been stabbed on two occasions, he still got around.

The weather was unseasonably warm. December 2 had set a record of 72 degrees Fahrenheit, and the mild temperatures continued throughout the month. Palulu was overdressed, wearing a heavy overcoat, which is what you expected to wear in New York in the winter. He was accompanied by his new bodyguard, Argelio Cuesta, who was a recent refugee from Cuba, part of a wave known as the Mariel boatlift.

The “Marielitos” were refugees whose exodus had been negotiated by President Jimmy Carter. At the time, Cuba was experiencing one of its periodic refugee crises. In Castro’s Cuba, securing a travel visa to leave the country was a near impossibility. It was one of the more pernicious aspects of modern Cuba that the island had become like a penal colony. If you wanted to leave for any reason, it became necessary to create some kind of homemade vessel—a raft or inner tube or makeshift boat—and attempt to cross the ocean at nightfall. Already, thousands of Cubans had died attempting to make this journey, and in the decades ahead thousands more would perish.

In April 1980, President Carter announced that the United States would take in refugees from Cuba if Castro would allow them to leave. A week later, Fidel announced that anyone who wanted to could leave. They would be allowed to embark from Mariel Harbor.

Over the next six months, from April through September, Cuba would experience an exodus unlike anything that had been seen before. Packed onto boats and other sailing vessels, a total of 125,000 asylum seekers flooded into the United States. They were processed primarily at immigration camps in Miami and elsewhere in South Florida. The majority were granted political asylum. Some journeyed beyond Miami to other localities with sizable Cuban populations, such as Hudson County in New Jersey, and New York City.

The Marielitos came from extreme economic deprivation. Some were criminals and mental defectives, whom, unbeknownst at the time to the United States, Castro had taken the opportunity to release as part of the exodus.

In the Cuban American underworld, the Marielitos represented an influx of desperate men, some of whom were willing to do anything for a price. They were recruited as gangland hit men, criminal errand boys, or, in the case of Argelio Cuesta, as bodyguards for someone with a longtime bounty on his head—a job not many people would want to undertake.

In Brooklyn, Cuesta and his boss, Palulu, were enjoying the mild December air when a team of hit men drove up and opened fire. Both men returned fire. Palulu was hit, but the wound was not fatal. Having Cuesta as his bodyguard probably saved his life. Palulu was rushed to the hospital. Gunshot wounds; hospital emergency room; a visit from the cops; and once again charged with possession of a weapon—a routine so familiar to Palulu. But at least he was alive; he had survived another hit attempt.

Upon learning of this latest failure, Battle was angry enough to cause the earth to rumble. In a way, he blamed himself. It had been a half-assed attempt, one that was beneath the dignity of a true Mob boss. Partly it was because he had put out an open contract on the street. The attempts to kill Palulu had become like a turkey shoot, where anyone with a gun had an opportunity to collect the $100,000 fee.

Battle needed to step up his game. And so, he turned to Lalo Pons, the head of his SS squad, who had distinguished himself as an organizer of hits and other acts of mayhem on behalf of the Corporation. Pons was given the assignment to exterminate Palulu.

By April 1983, Palulu had been released from the hospital and was out on bond awaiting yet another trial for possession of an illegal weapon. He had done something he did not want to do: he had moved into his condo in Riverdale. The condo was Palulu’s symbol of achievement that he had not wanted to tarnish by dragging into his life of crime and violence. But he had no choice. The condo was the closest thing he had to a sanctuary. Far removed from the teeming Cuban enclaves of Union City, Brooklyn, or the South Bronx, it created for him the illusion of safety.

On a blustery evening, Palulu returned to the condo with Cuesta, his trusty Marielito. He entered the building, using his key, and pushed the button for the elevator.

Neither Palulu nor Cuesta noticed that there was a man hiding in a mass of artificial shrubbery that decorated the lobby. The man crept out from behind the shrubbery and rushed up on the two men from the rear.

Clearly this attempt had been designed so that the gunman could get as close to his target as possible. This would not be a drive-by shooting, or someone taking potshots from a distance. This would be up close and personal.

The gunman put the gun to the back of Palulu’s head and pulled the trigger. Blood sprayed on impact, and Palulu fell to the marble floor. The shooter then quickly fired two shots at Cuesta, hitting him twice in the back. The bodyguard also collapsed onto the floor. The gunman ran out of the building.

A first-floor neighbor heard the gunshots and came into the lobby, where the two men were lying in pools of blood. Fire/rescue units arrived, and Palulu and Cuesta were rushed to Columbia Presbyterian Hospital, across the Harlem River at the upper tip of Manhattan.

There, in the emergency room, it would be determined that the bullet that entered Palulu’s head had miraculously skirted around his skull and never penetrated his brain. He was alive. In fact, it wasn’t even that bad an injury. The bodyguard, Cuesta, had also survived.

From his hacienda south of Miami, Battle received the news of yet another failed attempt on Palulu. Each time that his nemesis survived, Battle felt as if it took years off his own life.

Rumors circulated that Palulu was somehow protected by the orishas, the Santería spirits. He was protected by a bembe. This necessitated that Battle visit a babalawo and do his own bembe to overpower Palulu’s bembe. The effort to kill the one-legged gangster was now not just a matter for mortal men; it was a war between the spirits, competing babalawos, who conjured the power of various deities to manipulate the course of events in their favor.

Even after a full Santería ceremony with lots of candles, a sacrificial chicken, chicken’s blood, some rum, and lots of cigar smoke, Battle left nothing to chance. He got on a plane and flew to New York.

This time, the hit would be painstakingly plotted out. Lalo Pons recruited a hit team of two Cuban American brothers, Gabriel and Ariel Pinalaver. The brothers were considered to be fearless killers who could get the job done. They would be backed up by a second team of hit men.

The hit would take place in a section of the Bronx known as Belmont, a working-class Italian neighborhood. Palulu had recently opened a lottery office on East 180th Street, from which he ran a modest bolita operation. After Palulu was followed for weeks to establish his routine, it was determined that he arrived at his lottery office late at night. The hit men would stake out the location, wait for Palulu, and shoot him outside his office.

Battle wanted to be there, near enough to the location so that he could respond immediately when the shooting occurred and verify for himself that Palulu was dead.

On the night of September 28, an hour before midnight, Palulu arrived in Belmont in his car. He drove around the block a few times looking for a parking space and eventually wound up having to park a couple blocks away from the building where his office was located, near the corner of 180th Street and Arthur Avenue. He got out of his car, locked the car door, and began limping along 180th Street. When he got near the intersection with Arthur Avenue, suddenly two cars approached, coming from different directions. One car pulled up in front of Palulu, blocking his way; Palulu turned to flee, but the other car screeched to a halt from behind, blocking that direction. Out of the car popped the Pinalaver brothers, armed to the gills with assorted weapons. They opened fire on Palulu, riddling him with 11 bullets.

Palulu twisted in the street and fell face first onto the pavement.

He was pretty sure he was dead. Or maybe not. He could hear the sound of voices, feet walking on the pavement. He heard someone walk over to him, sensed the presence of someone looking down at him, felt someone put a foot underneath his torso and flip kick his body over onto his back. He could feel the blood oozing from his body, blood gurgling from his mouth. Barely able to open his eyes, in a haze, he looked up and saw someone hunched over looking down at him. He squinted, tried to focus. Looked like… could it be? It was. El Padrino. José Miguel Battle. The boss was standing over Palulu. And he was laughing. This was the last thing Palulu saw before his whole world descended into darkness, and he fell unconscious.

Was this the end for Palulu?

A fire/rescue unit arrived and rushed Palulu to the hospital. One miscalculation made by Lalo Pons and his hit team was that there was a hospital just three blocks away. Palulu arrived at St. Barnabas Hospital already on life support. A trauma team began immediate heart surgery. They were able to restart his heart, but he soon lapsed into a coma and stayed that way, in grave condition, for the next few days.

Battle stayed in the New York area, at his condominium apartment in Union City, which he maintained even though he had now fully relocated to Miami. He intended to remain in New York until he received word that Palulu was dead.

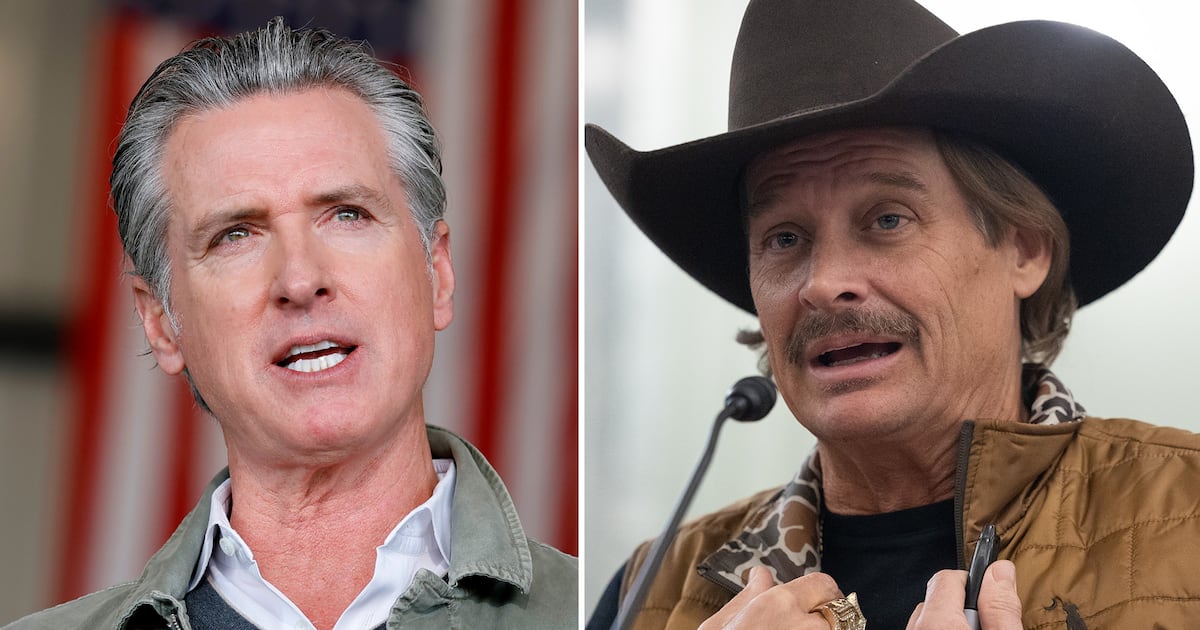

On October 2, five days after the shooting, Battle received word from a contact in the Bronx. The prognosis was not good. Not only had Palulu come out of his coma, but that afternoon Detective Kalafus of the NYPD had made a visit to his room. The pendejo was alive, and he was talking. Word was that he was in critical condition, but he had survived the shooting and given a statement to the New York detective who dressed like he was a cowboy from out west.

Battle and his people were stupefied, El Padrino most of all. He had seen Palulu for himself, riddled with bullets, bleeding to death in the street. He saw what he thought was Palulu expiring, savoring that moment as if it were a sweet kiss from the Angel of Death, the taste of revenge lingering in his gullet like fine Santiago rum. But now, it seemed, it was as if his eyes had played tricks on him. It was like many of his underlings had said: Padrino, he can’t be killed. He’s El Diablo. I shot him in the head. I know he was dead. But he’s alive. Incredible. I don’t even think he’s human.

Among other things, Palulu’s continued existence was causing great consternation for the Corporation, most notably the two men who were currently handling the day-to-day operations of the organization. Abraham Rydz and Miguel Battle Jr. had also recently moved to Miami. The move was motivated by Rydz’s needing to be near his dying mother, who lived in Miami Beach. Rydz and Miguelito purchased plots of land within a half block of one another in Key Biscayne, where they planned to build their dream homes. In Miami, the two men established a company called Union Financial Research. Ostensibly it was a mortgage lending company, but it was also a front for the bolita business in New York. Proceeds from bolita were being funneled into the company, which was based out of an office in Miami, with real employees, including secretaries, an accountant, and Rydz and Battle as CEOs.

Battle Sr. was no longer involved in the day-to-day operations of the bolita business, though he still collected his cut and took care of various matters of strategy, development, and, most of all, discipline and retribution.

The Palulu matter had been an issue for many years. Now, as far as Rydz and Junior were concerned, it had become a major distraction. El Padrino hardly talked about anything else. It was in everyone’s interest that the Palulu matter be resolved so that they could get on with their lives.

For the first time, Abraham Rydz, along with Battle Sr., Lalo Pons, and others among the ruling council of the Corporation, became involved in the planning of the hit. Everyone felt they needed to act fast. The idea was to kill Palulu while he was still in the hospital. The hit was planned quietly, so as few people as possible would know about it. The plan was devised by Rydz, among others, and Lalo recruited the gunman, a Cuban named Domingues.

On the night of October 7, two nurses were working the late-night shift at St. Barnabas Hospital, where Palulu was an inpatient on Wing Seven South, in room 711. Deloris Edwards and Romana Bautista were at the front desk. It was late—around 3:35 a.m.—a time when the hospital was at its most quiet. Suddenly, from down the hallway came a sound—Pop! Pop!

“Did you hear that?” one nurse said to the other.

They agreed that it was likely the sound of an oxygen line popping off its wall fixture, which was a chronic problem on their wing. Nurse Edwards headed off to check the rooms, while Nurse Bautista stayed at the nurses’ station working on paperwork.

At that moment, there appeared in the hallway a male nurse—or at least someone who the nurses assumed was a male nurse. He was wearing a hospital smock, like the other male nurses. But it was not anyone the nurses had seen before. He was Hispanic, with a caramel complexion, curly black hair, and a thin mustache. He had not checked in at the nurses’ station, as all nurses are required to do at the beginning of their shift.

“Hey there, hold up a minute,” Nurse Bautista called to the man.

The man did not respond; he quickly disappeared into a stairwell.

Meanwhile, that popping sound earlier had awakened Leroy Middleton, a patient in room 711, which he shared with Palulu. Middleton roused himself from a medication-induced slumber, got up, and headed to the toilet to urinate. As he walked past Palulu’s bed in the semidarkness, he saw what he thought could be blood, but he wasn’t sure what he was seeing. He went into the bathroom, peed, then walked back out to the room. By now, his eyes having adjusted to the darkness, he walked over and looked at Palulu, whose face was covered in blood. Leroy pushed the emergency call button.

The nurses rushed into the room and flipped on the light. What they saw was a ghastly sight: Palulu Enriquez had been shot multiple times at close range.

The hit was diabolical but effective. Domingues, disguised as a male nurse, had sneaked into Palulu’s room and done the deed. No doubt there were people in security at St. Barnabas who had been bought off to facilitate his entering the hospital and making his way to Palulu’s room without being stopped or questioned.

Palulu was finally dead.

It had been part of the plan that none of the originators of the hit—Battle Sr., Rydz, or Lalo Pons—would be in the New York area when the killing occurred. In the interest of plausible deniability, they were to be as far away as possible. Both Battle and Rydz had returned to Miami days before the hit was scheduled to occur.

On the afternoon of October 7, Battle, Rydz, and a handful of others were engaged in a card game at El Zapotal, Battle’s home in South Miami. It had become one of the ironies of the Corporation that the brain trust of the organization was now almost completely based in Miami, while the business—and most of the events that shaped its fortunes—still emanated from the New York metropolitan area. And yet the universe of the Corporation was clearly defined and circumscribed; it had become a mind-set not necessarily defined by geography but by mutual interests. The Corporation had become an entity that defied time and space.

At the card game, Battle received a phone call. He left to take the call and then returned, grinning from ear to ear.

“It’s done,” he announced to the handful of men at the table. “Palulu is dead.”

Abraham Rydz breathed a big sigh of relief. He immediately got on the phone with Nene Marquez, the Brooklyn boss of the Corporation, and authorized the release of $100,000 from the UNESCO fund to be paid to Domingues and a couple of others who had helped with the logistics involved in carrying out the hit.

Battle had stored on ice a dozen bottles of Dom Pérignon. He cracked open a few of them and poured champagne for everyone in the room. The men extended their glasses, and El Padrino proclaimed, “Let’s drink champagne and raise a toast to our enemies. Drink up.”

It was an auspicious occasion. After all these years, José Miguel had finally avenged the murder of his little brother.

The partying did not stop there. For the next week, Battle celebrated the death of Palulu. There were impromptu parties at a couple of favored restaurants in Miami, and parties at El Zapotal. Guests at the house noted that as they arrived, there was a new wrinkle, something they had never seen before. Upon entering the front door, each guest was individually presented with a small pouch. What is this? they asked. When they opened the pouch, they found out: cocaine. Each pouch was filled with cocaine.

Let the festivities begin!

Copyright 2018 by T.J. English and reprinted courtesy of William Morrow.