As his two daughters tell it in their first extensive interview, the Harlem drug lord once proclaimed “Mr Untouchable” on the cover of the New York Times Magazine spent his later years as “Mr. Respectable.”

Where Leroy Nicky Barnes once ruled a conglomerate of heroin dealers known as The Council, he went to work at a suburban Walmart in the Midwest.

Where he once sold thousands of pounds of heroin for millions of dolls, he punched in a time clock for an hourly wage.

Where he once chose from a fleet of luxury cars, he went about in what was just another used car in Middle America.

Where he once had hundreds of custom tailored suits, he wore sweatshirts and jeans.

But he was still him.

“Even when he wore jeans he still ironed them,” his younger daughter reports. “Everything was pressed and creased.”

Ultimately, he seemed to have become more exactly himself after all the decades spanning from his street days to a life sentence to turning informant and entering the witness protection program. He had been given a new identity, but seemed to remain what he had always been at his core, what he might have more manifestly been from the start had he been raised in the suburban circumstances where he passed his later days.

“He was comfortable in his skin,” the older daughter says.

From the point of view of both daughters—who themselves have been given new identities in witness protection—Barnes ended his days as the dad of their earliest memories.

The elder daughter remembers him teaching her how to swim and how to write her first and last names when she was no more than 5. She also recalls grabbing hold of his muscular bicep.

“I would hang from it and kind of swing,” she says.

The younger daughter also remembers the bicep swing, though she was not more than 2. Both daughters remember him playing with them and occupying a big part of their lives.

“Kind of like that larger-than-life presence, and I was so little,” the younger daughter says.

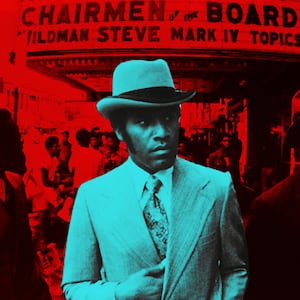

But then came that photo on the cover of the June 5, 1977 edition of the New York Times Magazine. The accompanying text employed a nickname he acquired after beating two state drug cases.

“‘Mister Untouchable,’” the cover line read. “This Is Nicky Barnes. The Police Say He May Be Harlem’s Biggest Drug Dealer. But Can They Prove It?”

President Jimmy Carter saw the cover and is said to have ordered the Department of Justice to make sure Mr. Untouchable did not also beat federal charges that were then pending against him. Barnes was convicted six months later.

“He was framed for something he did,” columnist Murray Kempton suggested.

Barnes was sentenced to life in prison. His daughters were brought to visit him in prison by their mother, who is said to have assumed an active role in the continuing heroin enterprise.

By 1982, Barnes had become convinced that the girls’ mother and the members of the Council were betraying him. He became a federal informant and agreed to testify against the entire organization, the girls’ mother included. She was sentenced to 10 years in August of 1983.

With both parents in prison, the daughters—then aged 10 and 8—were placed in foster care. The daughters will only say of their mother that she was released after six years and remained a part of their lives, but no longer had a relationship with their father.

In the meantime, their still incarcerated father had vanished into the witness protection program.The daughters were also enrolled after federal authorities got word they had been targeted. The older daughter had to begin using a name other than the one her father had taught her to write.

The daughters were able to be in periodic touch with Barnes. He took a particular interest in their education.

“He would try to do homework with us over the phone,” the younger daughter says. “Given the circumstances, he tried to be the best dad he could.”

The daughters know that one of his torments behind bars was continued concern how they would turn out as a result of the challenges they faced.

“I know he just worried and worried and worried,” his older daughter says.

In August of 1998, Barnes was released, having served 21 years. He was 64 and had earned a college degree in prison, even written award-winning poetry. He was allowed to settle near his daughters, who were 26 and 24.

After two decades in prison, Barnes marveled at the fast pace of a Midwestern suburb that he previously would have found to be the municipal equivalent of a sleepy yawn.

“He couldn’t believe how fast people moved around,” the younger daughter recalls. “How fast people walked.”

The daughters figured their father’s amazement as well as his surprisingly slow pace resulted from his years behind bars.

“He only had so many feet to maneuver,” the older daughter says.

When they were out walking with him, they would suddenly realize he had fallen behind.

“Oh, we got to slow down because dad’s behind us,” the older daughter would remember telling her sister.

Barnes also may have been distracted in the way of a tourist by the sights and sounds of a foreign land.

“It was just a completely different world,” the older daughter says. “Different In every way you can imagine.”

The daughters now had children of their own. Barnes admired their attentive and loving parenting style, so different from what he had experienced while growing up amidst a myriad of social ills. He had been driven from his Harlem home by an abusive alcoholic father and had been arrested for robbery before he turned 10. He had been a junior high school dropout and then a drug addict for a time before being sent to a federal treatment facility in Kentucky. He had then gone from using heroin to selling it.

“I remember him saying he was a product of his environment and if he had parents how we are with our children it would have been different for him,” the younger daughter says.

He told his daughters that his life might have taken any number of different courses had he been raised as they were raising their own kids.

“He would have had a choice,” the older daughter says. “The ability to choose.”

His choice now was to focus on the positive, not on what might have been, but on what could still be.

“He didn’t dwell,” his older daughter says. “He was really very present, very kind of in the now.”

His years and years behind bars of worrying and worrying about his daughters now ended in happy relief.

“I am so proud of the way you turned out,” he told his daughters by their recollection.

And felt sure their kids would have even more choices.

“He had no concern about whether or not they would be well educated,” the younger daughter says.

He delighted in being a grandfather. He happily babysat and attended school performances and sporting events.

“He was grandpa,” the younger daughter says. “He just was always there.”

He settled into a suburban apartment and went to work at a local Walmart. He actually seemed to like the time clock routine.

“Punch in, punch out,” his younger daughter says.

The daughters report that he was unflaggingly enthusiastic as Walmart assigned him to various departments.

“He gave it 100 percent,” the younger daughter recalls. “He wanted to learn everything in every department.”

He pursued a daily routine as if it were a route to redemption.

“Work long hours. Go home. Make dinner,” his older daughter says.

He telephoned his daughters every couple days and visited them regularly.

“Just a part of our lives,” the younger daughter says. “Kind of normal for the circumstances, I would say.”

He was aware that there were still people from his former life who wished him serious harm.

“I think he knew there was always the possibility of something happening,” his older daughter says. “He erred on the side of caution.”

He cut himself off from those he had known in the drug business and in prison. His best protection beyond that was to melt into his new surroundings.

“He really wanted to just blend in,” the older daughter reports.

Except for the creases in his jeans, he was just another Walmart employee. And his new identity was all the more convincing because he seemed so content to be living it.

“He was very thankful for the opportunity to just work and earn an honest living,” his younger daughter says.

“He was so grateful to be able to go to work everyday and not look over his shoulder.”

The older daughter notes, “He didn’t want that untouchable persona any more.”

One complaint he did have about his new life came with winter.

“He hated cold,” the younger daughter says.

And that reinforced a continuing difference between him and a good number of his co-workers.

“He didn't engage in that typical outdoor Midwestern activity,” his younger daughter says. “He’d rather be reading inside.”

One constant since his drug kingpin days was a love of books.

“He spent a lot of time in the public library,” his older daughter says of his new life.

He retained a pre-incarceration passion for Shakespeare. His favorite play was Othello.

“He talked about the Moor,” the older daughter says.

He recommend books for grandkids and clipped out articles for them to read.

“He would always follow up and ask, ‘Did they read it? Did you give it to him?” the younger daughter recalls.

At family meals, he would discuss politics and current events and pop culture.

“Our conversations around the dinner tale were much like any other family,” the younger daughter says.

He sometimes turned on the TV at home, but it was to news or sports. He liked CNN and MSNBC, Rachel Maddow in particular.

And he cheered when Barack Obama was elected president.

“It was something he didn’t think he would see in his lifetime,” the younger daughter says.

In the meantime, a lesser heroin dealer named Frank Lucas became the subject of a New York magazine article that become the basis for the movie American Gangster. Barnes still had his pride and just enough Mr. Untouchable in him to risk surfacing from obscurity with a 2007 autobiography followed by a documentary. He had returned to anonymity when he became terminally ill with cancer.

On June 18, 2012, Barnes died in the company of his daughters. He was 79 and had been free for 15 years.

“He was always surrounded by family,” the younger daughter says, “Up until the day he passed.”

The daughters held a quiet private memorial and his death was recorded under the name he had assumed. His passing escaped public notice until this year, when Frank Lucas’ death prompted questions of whatever happened to Nicky Barnes.

The world learned the answer in June, when the enterprising and intrepid Sam Roberts of the New York Times wrote an obit headlined, “Nicky Barnes, ‘Mr. Untouchable’ of Heroin Dealers, Is Dead at 78.”

Other imprisoned big-time criminals who won their freedom by becoming big-time informants have reverted to their old ways while seeking easy money. Frank Lucas was busted in a post-incarceration drug deal. Mafia underboss Sammy “The Bull” Gravano was sent back to prison after he had his own son sell drugs.

But, by his daughters’ account, Barnes had been happy to be making an honest living. And he had found fabulous wealth of another kind in his daughters and grandkids. Mr. Untouchable had become not only Mr. Respectable, but also Mr. Lovable.

“Affection and hugs,” his younger daughter says. “We always said, ‘I love you.”

He leaves behind what his youngest daughter calls ”a big void in our lives.” Both daughters report they are grateful for the time they did have with him.

“For him to be with us just answered so many prayers we had as little girls,” the older daughter says.