TIJUANA, Mexico—Guadalupe Olivas Valencia was deported to Mexico on Tuesday morning. He was handed the last of his possessions in a clear U.S. government-issued plastic bag, and dropped off in Tijuana, at the international border dividing the United States from Mexico.

Less than an hour later he was dead.

Olivas was deported for at least the third time in his troubled life on Tuesday morning, but this time it would be his last. He leaped to his death from a pedestrian bridge at the international border, landing in a concrete river bed a stone’s throw from the metal fences meant to keep people like him out of San Diego, out of California, and out of the United States.

Hospital authorities said he was pronounced “dead on arrival” at 9:26 a.m. And witnesses told local media outlets that he appeared distressed in his final moments of life.

His mother said she last saw Olivas on Sunday. But on Monday, he crossed the border seeking asylum, which was promptly denied. U.S. authorities said in a statement that he “was found to be inadmissible.” So, on Tuesday morning he was repatriated to Mexico.

He telephoned his mother just moments before his death on Tuesday “to say goodbye.” And on Wednesday, she tearfully collected his corpse.

“His three children—who are 11, 19, and 21—are so sad, and his mother is devastated,” said Olivas’s aunt, Irma Delgado, during her nephew’s wake on Thursday night.

His three children arrived yesterday from their home town of Los Mochis, in the cartel stronghold of Sinaloa, from which Olivas’s mother came 30 years before with his six siblings to look for work.

After his funeral on Saturday, Olivas’s youngest daughter will return to Sinaloa to live with her maternal grandmother, taking her father’s ashes with her.

“His wife died three years ago. He couldn’t find work, or opportunity, and he felt so much desperation,” Delgado explained. “I don’t want to blame the president of the United States. I don’t want to blame him, he is just taking care of his country, but this does send a signal to immigrants in the U.S. and it is cause for worry.”

Even Olivas’s aunt, who has a visa that allows her to cross the border, was worried about whether news of her nephew’s suicide would affect her visa. “I hope they don’t try to take it away from me now,” she said.

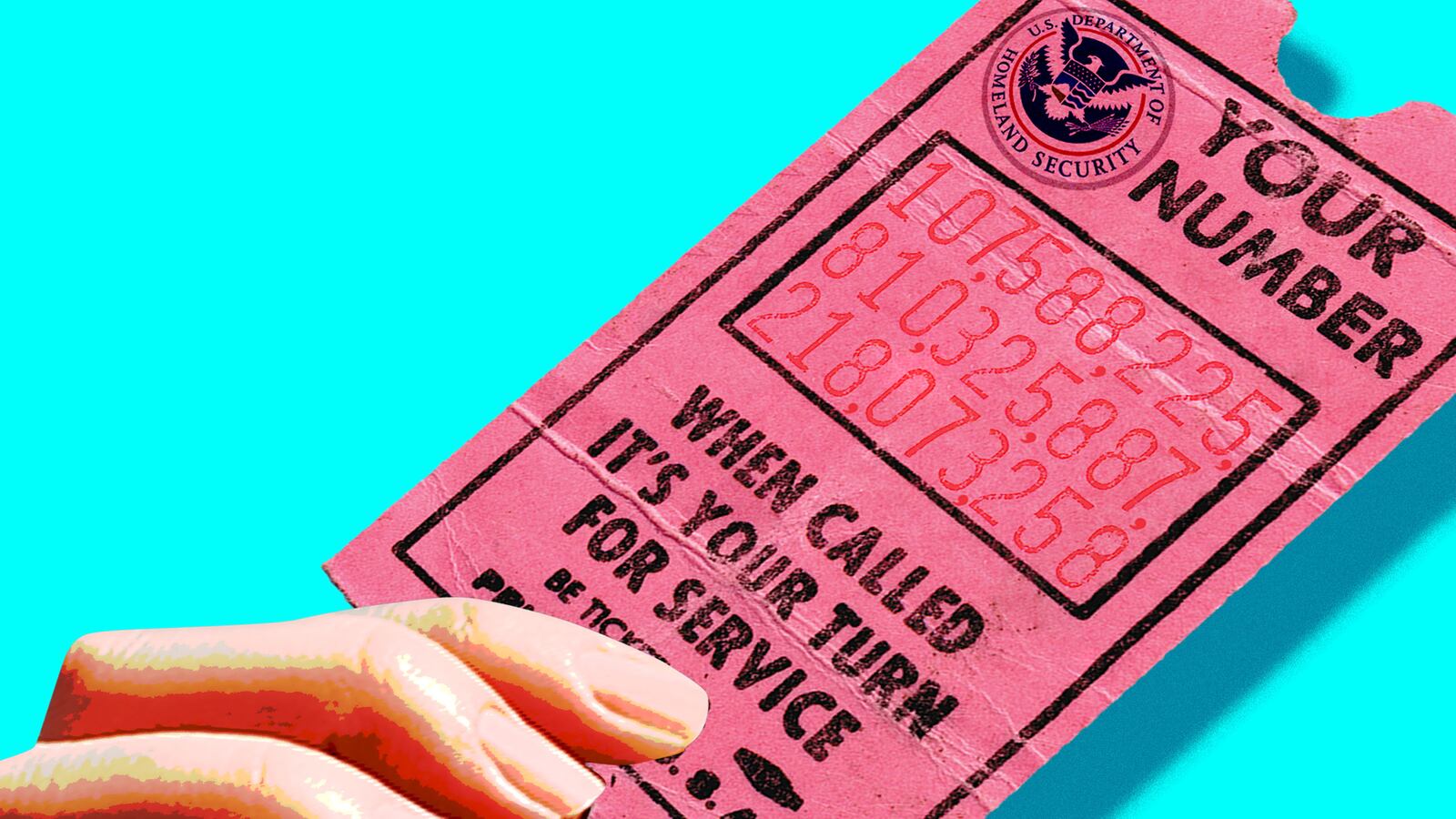

As reports of Olivas’s death spread on social media this week, dozens of comments began to appear online. Those left in Spanish overwhelmingly lamented his passing. But in English, response to the news was mixed, with many variations on the theme, “Why didn’t he just get in line and cross the border legally like everyone else?”

“My dad’s immigration process took 14 years,” one California resident I spoke to said on Thursday. “Y'all literally don’t know what you’re talking about when you say just become a citizen.”

***

News of Donald Trump’s proposed plans to increase deportations spread throughout the United States, leaving thousands on edge, regardless of their legal status. Memos released last week outline the Department of Homeland Security’s plans to enforce President Donald Trump’s executive order to deport as many undocumented immigrants as possible. The result has been a wave of fear.

For Trump, illegal immigration “presents a clear and present danger to the interests of the United States” and is therefore a number one priority now as it was during the campaign. His Jan. 25 executive order calls for increased measures to keep “those who illegally enter” and those who he deems “a significant threat to national security and public safety” out, and would focus on those he claims “seek to harm Americans through acts of terror or criminal conduct.”

The new guidelines will expand the use of “expedited removal” deportation procedures —previously reserved for those detained within 100 miles of the border, like Olivas. Now it will apply nationwide, which means that now immigrants can be removed without going before a judge or being allowed a court hearing.

The memos point out those who will be targeted first will be immigrants previously convicted of or charged with a crime. But, it would also include those who have not been, yet could be, like those who have knowingly misrepresented themselves—immigrants who use others’ social security numbers to seek employment. Caught up in the broad sweep would be any undocumented immigrant who has received public benefits, and more broadly still, anyone who “in the judgment of an immigration officer, otherwise pose[s] a risk to public safety or national security.”

On this last point, the plan is to deputize local and state law enforcement officials, allowing them to serve in the spirit of immigration enforcers nationwide.

Fears have peaked as word of broad and unreasonable searches and detentions have been reported, like that of a Salvadorian woman in Texas, who while awaiting emergency brain surgery to remove a tumor was forcibly relocated by federal agents to a detention center on Wednesday. Or the dozens of passengers on a domestic flight to New York on Wednesday whose documents were reviewed by Customs and Border Protection (CBP) agents while they searched for an immigrant who did not board the plane but had been scheduled for deportation on criminal grounds.

In the wake of the crackdown, several agencies have already stepped up to express their discontent, clarify their role, or outright refuse to comply with federal laws.

The Boston transit police tweeted on Thursday, “Transit police officers do NOT enforce Federal Immigration laws. We are here to serve everyone,” adding that they will continue to participate in counterterrorism efforts. The city of New York, a “sanctuary city,” tweeted the following reminder: “NYPD will not ask about the immigration status of New Yorkers seeking help or reporting a crime. Period.”

But rebelling against Trump’s orders will be costly business, and subject so-called sanctuary cities to massive cuts in federally allocated funds. New York Mayor Bill de Blasio said in January that his city would be putting $250 million a year away in reserves, citing the “huge amount of uncertainty” the city will be facing. But New York is not alone in its dissent. Chicago, Los Angeles, Detroit, San Francisco, Boston, and Washington, D.C., are just a few of the cities whose funds will be at risk.

On Thursday, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson and Secretary of Homeland Security John Kelly traveled to Mexico City to meet with officials and discuss the changes to come.

Mexico’s foreign minister, Luis Videgaray, said during a joint press conference on Thursday alongside Tillerson, he was “grateful” for the visit, adding that it comes at a “complex moment for the relationship between the United States and Mexico” when Mexicans have grown “worried” and “irritated” at the recent changes in immigration policy.

“We have expressed our concern to Secretaries Tillerson and Kelly over the respect toward the rights of the Mexicans in the United States, in particular their human rights,” Videgaray said. He rejected the idea that one government—the U.S.—would be “making unilateral decisions” that would affect the other.

“We don’t have to” accept these decisions, he said. “It is not in the interest of Mexico.”

But Videgaray responded to the attacks against Mexican immigrants, by partially deflecting the blame further south, addressing the two countries’ “shared responsibility” to resolve the Central American migration that impacts them both—in particular migration stemming from Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador—and said that “steps in the right direction” were taken during Thursday’s meeting.

***

“Mexico has been a close neighbor,” Tillerson said, following Videgaray’s prepared response. “In a relationship filled with vibrant colors, two strong sovereign countries from time to time will have differences.”

Tillerson placed particular emphasis on the Unites States’ and Mexico’s “joint commitment to maintaining law and order along our shared border by stopping potential terrorists and dismantling the transnational criminal networks moving drugs and people into the United States.” He also spoke of the “importance of stopping the illegal firearms and bulk cash that is originating in the United States and flowing into Mexico,” an often disregarded point on the United States’ role in the violence affecting Mexico’s most embattled regions.

But while these important issues were discussed, both countries failed to speak about the comprehensive immigration reform that would be necessary to put an end to the illegal immigration that the U.S. has made its primary concern.

Under current policy, Mexican citizens may pursue one of three legal pathways to entry, each with high hurdles to overcome.

Migrants may be allowed in if a U.S. employer sponsors them, which would require them to have somehow lined up a job in the U.S.—and one for which they are uniquely qualified, which cannot be filled by someone already in the U.S. This policy, by design, bars immigrants who have not had educational and economic opportunities in their home country, and caps are placed on how many visas for skilled workers are granted each year.

Caps are also placed on how many immigrants are allowed in who are not closely related to a legal U.S. resident—only children, spouses, and parents are exempt. But even when closely related, immigrants may not come in if their sponsor family in the U.S. still earns an income that is below the poverty line.

The poor and the undereducated are overwhelmingly left without legal migration opportunities by this policy, by design.

The best shot that migrants fleeing lack of opportunity, poverty, and violence in their home countries have is to apply for humanitarian asylum, like Olivas did on Monday, the day before his suicide.

But, like Olivas, many of those who seek asylum are denied entrance outright, and often even denied access to the authorities tasked with making the call.

***

Back in October, before President Trump took office, in an interview with The Daily Beast, Elida, a mother of eight children, described her attempt at seeking asylum in the U.S., after her husband was kidnapped by cartel members in the violence-afflicted state of Michoacan.

She was living in Tijuana then, in a migrant shelter for women in children, having arrived just days after cartel members shot down a government helicopter in her hometown, La Huacana. The cartel, she said, “were coming back for my daughter, so they could use her for themselves.”

“They see a little girl and say, ‘Come here chiquita, open your legs’,” she said. “Of course, we had to leave.”

But when she arrived at the U.S.-Mexico border in Tijuana, as perfect a candidate for asylum as there ever was, with no criminal record, a disappeared husband, nothing left to her name, and credible fear for her life, and the life of her daughter and remaining children, she was denied asylum, detained for three days, locked inside “the freezer”—an over air-conditioned detention cell—with her minor daughter, and sent back to Mexico, where volunteers gave her clothes and a bed to sleep in.

“I thought the americanos would help,” she said. “But instead they said that I’m now deported and can’t come back.”

Because she sought asylum, she has been flagged as a criminal, and blown her only chance at humanitarian asylum in the U.S.

“I didn’t jump over a fence or swim across a river,” she added. “I was just asking for help.”

Speaking last week to Tijuana-based immigration attorney Nicole Ramos—who was featured in a recent VICE News segment “Asylum Seekers Are Being Turned Away Illegally At U.S.-Mexico Border,” in which secretly recorded video showed a Central American migrant being denied access to asylum authorities at the border—Ramos explained to me that she almost always faces trouble with U.S. authorities at the border, and is often forced to read them sections of federal code while demanding her clients’ rights.

Nicole shared stories of several recent interactions that she has had with border officials while accompanying clients—clients who have been turned away at the border, denied credible fear interviews, and directed back into Mexico to visit with Mexican officials.

One of her clients said that in the days following Trump’s order to enact a partial Muslim travel ban, a Mexican female asylum seeker was turned away at the border and reminded that there are people from “other countries where Christians are being persecuted and killed” seeking asylum.

“Those are the people that we’re taking in. Not you people,’” according to Ramos, who was repeating what CBP officers told her client, who was illegally denied access to an asylum interviewer. “I think that was directly related to the executive order—the travel ban. But they don’t have the authority to do that.”

“They are making judgment calls that are not within their authority, instead of redirecting these cases for asylum interviews. CBP is pretty aggravated with me, because I do a lot of these cases pro bono, so they aren’t used to people coming in knowing what their rights are,” she said. “They claim I’ve been coaching my clients to lie to the authorities.”

Ramos recalled recently being threatened by CBP authorities, in the days following Trump’s executive orders, with authorities claiming they will have her processed for removal. Ramos explained that roughly 20 asylum seekers come to her for consultation each month. “This number has picked up since the election, because people are concerned that the border is going to close for them,” she said.

“CBP states publicly that everyone is being processed in accordance with the law, and that no one is being denied a ‘credible fear’ interview and that everything is running smoothly, but that’s just not true,” she said. “When I’ve brought people they have tried to turn them away, even in the presence of an attorney.”

Other asylum seekers have been processed by officials who’ve improperly filled out their processing forms, claiming that they claim no credible fear if they are returned to their home countries, she noted.

***

The day we spoke, Ramos had just returned from the border, where she accompanied two unaccompanied Colombian minors, who should be entitled to special protections under the Trafficking Victims Protection Act. There, she was told that the children had to go meet with Mexican authorities first.

“What happens if you present a minor to Mexican authorities is you run the risk of them being placed [in child welfare protective custody in Mexico] and then potentially being deported,” Ramos said, adding that she refused to turn in the children, and demanded to speak to a supervisor.

“The pattern of basically telling asylum seekers to kick rocks has been ongoing, and they’ve become more aggressive in turning asylum seekers away in recent months,” Ramos said, adding that many of her clients—like Central American migrants who are not necessarily in Mexico legally—are put at risk by being blocked at the border and told to visit with Mexican immigration authorities first, at an office conveniently located right next to the Mexican immigration detention center.

“I think that the changing climate politically is emboldening these officers to take specific actions and to do things that they maybe used to do less blatantly,” she said, adding that Trump’s stance on immigration “gives border authorities more freedom to practice their racism more openly.”

“Since January I’ve had three Mexican asylum seekers turned away and told categorically ‘Mexicans do not qualify for asylum at this point in time,’” Ramos noted.

So, the current, unreformed immigration policy denies those seeking entrance reasonable access to the mythical “line” they are supposed to get into, which would allow them to emigrate legally.

Worse, it does so on the grounds that they are too poor, too undereducated, and indeed “too Mexican” to deserve the opportunities that the government and right-wing pundits claim they would have access to, if only they would try pursuing entrance legally.

The U.S. government, under President Donald Trump, has made the focus of its administration the building of a monstrous wall. But, so far, it has not proposed a gateway to entrance.

But those among us who do not understand this discrepancy continue to demand “they should just get in line like everyone else,” without considering the fact that—for those most in need—once they reach the front of the line, all they will see is more of the same wall they convinced themselves not to jump over.