Barbie turns 55 today, and she doesn’t look so good.

Despite a flurry of PR in the constant quest to keep America’s original teenage fashion model doll relevant—including a controversial Sports Illustrated spread and a partnership with the Girl Scouts—Barbies aren’t flying off the shelves like they used to. Girls are ditching the teen dream, yes for iPads, but also for low-tech activity toys and for dolls with more interesting stories to tell.

While it’s tempting to credit feminists and academics with winning a long-waged war on the hyper-sexy doll’s promotion of an unhealthy body image and an outdated, milky white vision of beauty, the ultimate reason for her domestic demise might actually be due to the fate that often awaits some old ladies: Barbie got boring.

A study from Oregon State University released this week shows playing with a Barbie actually weakens a girl’s career ambition. Girls who were given Barbies to play with thought they could do fewer “boy jobs,” than girls who played with Mrs. Potato Head—results that held whether they played with a fashion Barbie or her stethoscoped counterpart.

Also this week, two advocacy groups blasted the Girl Scouts for partnering with Barbie on a career choice booklet and a pink patch that sports a cloyingly stupid “Be Anything, Do Everything" slogan and a Barbie logo. "Holding Barbie, the quintessential fashion doll, up as a role model for Girl Scouts simultaneously sexualizes young girls, idealizes an impossible body type, and undermines the Girl Scouts' vital mission," said Susan Linn, director of Campaign for a Commercial-Free Childhood, one of the groups leading the charge.

Barbie isn’t immune to bad press and in 2013, it showed. Though she still dominates a steady $2.7 billion doll market, she peaked in 2002 and worldwide year over year sales dropped a whooping 13 percent over the most recent holiday quarter, six percent over the entire year.

Her abysmal numbers are a continuing trend for a company that’s struggled to recover from a Barbie crash caused in part by the success of competing brands under the Mattel umbrella. This year’s young stars include the infinitely more interesting Monster High dolls, gothy figurines inspired by creatures in classic monster movies, and American Girl dolls, an expensive but experiential toy that made up 14 percent of Mattel’s total sales in 2013 and continues to climb.

“The reality is we just didn't sell enough Barbie dolls,” Mattel CEO Bryan Stockton said in the most recent earning calls to explain another disappointing quarter.

But it wasn’t always that way. In the year after her release at the 1959 International Toy Fair, Mattel sold over 350,000 of the $3 mini-mannequins. Little girls threw aside their pudgy doll babies and begged their parents for the first American doll with a “teen-age” hourglass figure. Mattel successfully marketed them with jingles copping to the aspirational nature of their use. In the first commercial a woman purrs, “Someday, I’m gonna be ‘xactly like you / Til then I know just what I’ll do / Barbie, beautiful Barbie, I'll make believe that I am you.”

Over one billion Barbies have been sold worldwide since a 1964 article in The Saturday Evening Post called her “the hottest toy to come along since the balloon.”

She’s gone through several cosmetic changes over the years: eyelashes, a rotating waist, and a 90’s redesign that shrunk her breasts and widened her midsection. Perhaps the most feminist of them all came in 1971 when Malibu Barbie became the first of her kind to look straight ahead, instead of wearing a demure side-glance.

“We’re always challenging ourselves to think differently about Barbie and how we can continue to keep her relevant,” Lisa McKnight, Mattel senior vice president of marketing told The New York Times in February.

If these slight changes have been the secret to Barbie’s longtime success, why aren’t they working now? Why don’t little girls want to play with her anymore?

It could be that 55 years of criticism have finally caught up to her.

The impact of Barbie on the social and emotional development of girls was questioned from the start. At best, she’s been called confusing, and at worst, a menace to society.

Barbie has always been most reviled for her unattainable beauty and oozing sexuality. As a human she would be practically anatomically impossible. Researchers liberally estimate the chance of having a Barbie body in real life to be about 1 in 100,000. But public discomfort with her unrealistic proportions is really just the beginning of Barbie’s problems.

In 1968's Desexualization in American Life, Charles Winick, a sociology professor at CUNY, railed against the "sexy automatized doll" for introducing "precocious sexuality, voyeurism, fantasies of seduction and conspicuous consumption," to girls in their latency years. New York Times Book critic Eliot Fremont-Smith agreed in his review, calling Barbie, “singularly offensive.”

Mattel got in more hot water with the 1992 release of Teen Talk Barbie. With one press of her button, formerly silent Barbie blurts out, “Math class is tough!” After a censuring from the American Association of University Women for perpetuating negative stereotypes, the offending statement was removed from Barbie’s repertoire (though shopping and the dreaminess of Ken remained). But not before a group calling itself the Barbie Liberation Organization brought attention to the sexism behind the toys by switching what they claimed to be hundreds of Barbie voice boxes with G.I. Joes (Hasbro). “Dead men tell no lies!” the new badass Barbie growled.

Even the man who sculpted the original Barbie, Bill Barton, told newspapers that he had second thoughts about her curvaceous form. “Perhaps, when they were teens or approaching their teens, they looked in the mirror and said, ‘I’ve got zits. I’m fat. Barbie I’m not.’ Maybe it caused a false impression of what they wanted to look like.”

These concerns are backed by years of research fueled by academic fascination with the impact of the flirtatious figure on its young market. One notable study from 2006 found that meeting Barbie at an early age can damage a girl’s body image. In the experiment, young girls who were exposed to Barbie as opposed to “average” sized dolls or no dolls, agreed less with statements like “I’m pretty happy about the way I look.” And when asked to draw an ideal body size, more Barbie girls drew smaller shapes than ones they drew to illustrate their own, reflecting a negative body image.

Not so fast, Barbie backers argue. A working girl, with nearly 150 careers, Barbie is in fact, a pioneer with a “We Girls Can Do Anything” attitude (an actual slogan in the 80’s). She’s clocked in as a “career girl”, astronaut, presidential candidate, and at least eight different incarnations of a small child doctor or veterinarian.

Evidence to the harm the little model can do notwithstanding, how do you stop a problem like Barbie? Progressive parents have tried and failed to ban Barbie in their homes. Even Gloria Steinem told Newsweek, “You can’t forbid it, because that just makes us want it more.”

And you can’t escape the blonde hordes if you tried. By Mattel’s estimation, 90 percent of girls ages three to ten own at least one Barbie, which means any hopes of keeping little paws off Barbie’s curves takes a watchful eye.

On parenting listservs and mommy blogs, mindful moms and dads, while still concerned about the eventual effects of Barbie, report biting their tongues, and hoping Barbie will just go away. If sales are any indicator, the plan might just be working.

Heather Hunt, 38, who attends law school while raising her three-year-old, Ursula, has taken this more relaxed approach and says the interest in Barbie has waned. Though Hunt wasn't allowed to play with Barbie until she turned six (it was an age-appropriateness thing), she didn’t make a big deal about it when Ursula received her first Barbie as a gift last year, or the two more that followed.

“She undresses them because she likes boobies, but that's the extent of it,” Hunt says. More often, “she does things like make believe a pillow case is her batman cape. I think that she doesn’t know what to do with Barbie, so they are kind of boring.”

Still, Hunt wonders about the unrealistic model of beauty it might set. “I just want her to learn that there is more to being beautiful than a nice rack and blond hair,” she says.

Hunt’s not alone. And with each anti-Barbie wave, in rides a savior/entrepreneur promising to change the way our children play.

This week’s offering comes out of Pittsburgh, from artist Nickolay Lamm, who gives us Lammily, the normal-sized girl who teaches us (according to his tagline) that “average is beautiful.” The minimally made-up brunette—pretty, but plain, with clothes that say more homeschool than homecoming queen—is based on proportions of the average 19-year-old American woman, as measured by the Centers for Disease Control. Lammily is striking in her ordinariness. She’s generic, but that’s kind of the whole point.

Lammily hasn’t actually been made yet, but the $95,000 crowdfunding request to make her a real doll was fully funded in less than 24 hours. By Saturday evening, 9,700 backers had donated a total of $337,135 for a chance to own one of the real dolls.

Lamm says he only expects demand to grow. “People are excited that there is finally an alternative. I think this is what they've been waiting for, for many years.”

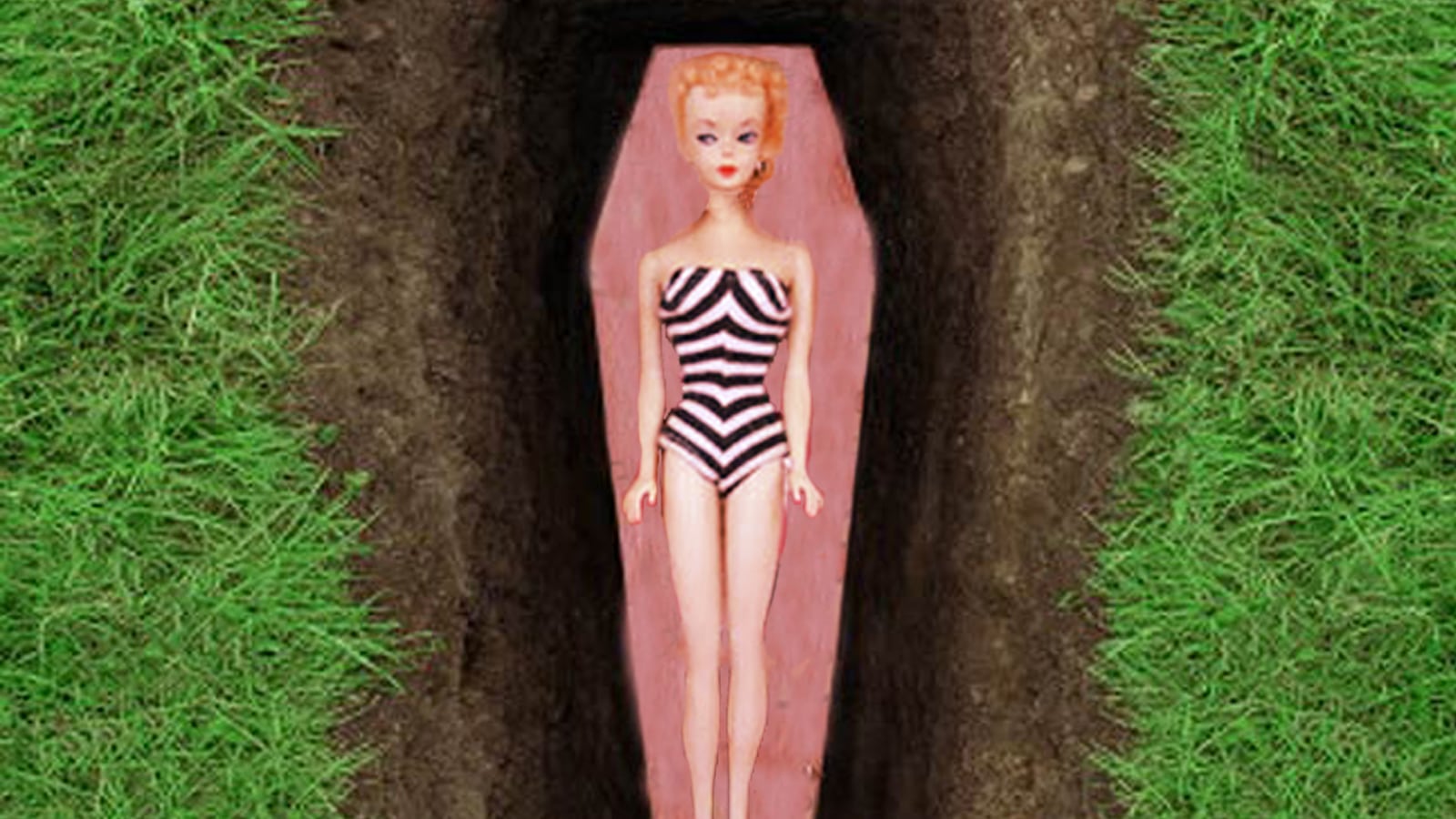

But he’s far from the first to market a more realistic version of the plastic doll. Somewhere a graveyard exists for all the alt-Barbies past. There was the politically correct "Happy to Be Me" doll in the 90’s, the sporty multi-racial Get Real Girls Inc. dolls, and The Only Hearts Club dolls (“really cool girls, just like you!).

Whether it’s Lammily or another, a new plastic figurine probably won’t stop half of the doll dollars from going straight to Barbie any time soon. Still, more choices have weakened her market share and will likely continue to do so.

But the biggest threat of all to the reining plastic princess looks to be girls themselves who want more from their toys than Barbie is able to give.