Cults make prophetic promises they can almost never fulfill, which in turn leads them to revise those guarantees in order to keep their flock in line and their scams alive. In that regard, few have faced a bigger obstacle than the Remnant Fellowship Church, whose founder and leader Gwen Shamblin routinely preached that being faithful to God—primarily by maintaining a slim waistline and training children to be docile and subservient—resulted in glorious financial, familial, and spiritual rewards. That was all well and good during the prosperous Remnant Fellowship times, but it became an onerous problem on May 29, 2021, when a plane piloted by Shamblin’s husband Joe Lara crashed on its way to a Florida MAGA rally, instantly killing Shamblin and everyone else on board.

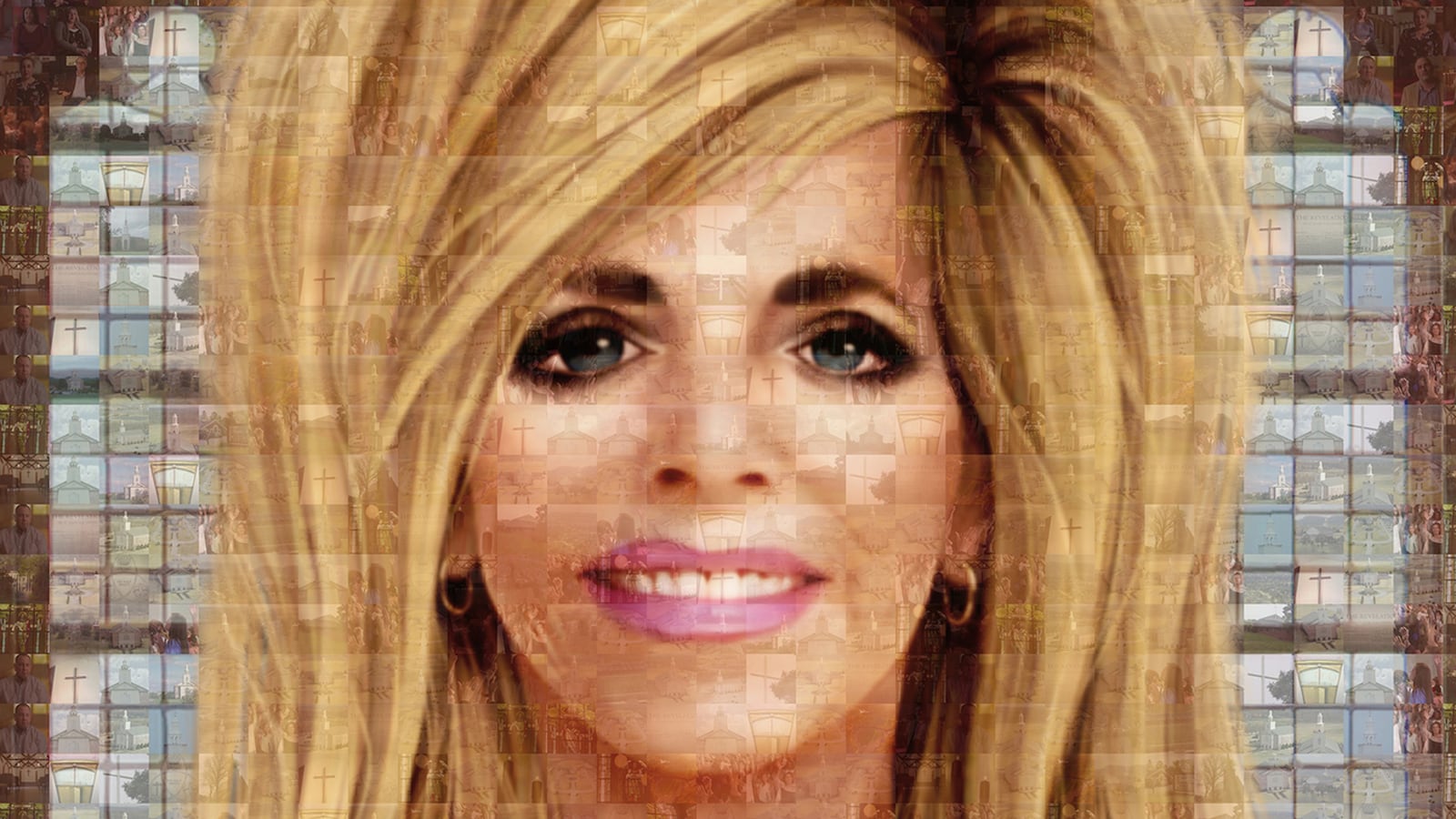

That tragedy served as a de facto cliffhanger for The Way Down: God, Greed, and the Cult of Gwen Shamblin, HBO Max’s docuseries from last September, and it’s where director Marina Zenovich picks up with The Way Down Part 2, a two-installment coda that investigates what this calamity has meant for the Remnant Fellowship Church and Shamblin’s attendant Weigh Down Workshop diet business. The latter was the vehicle that first brought fame and fortune to Shamblin herself, a nutritionist who argued that true believers should transfer their hunger for food into devotion to the Almighty. It was a program that contended that shedding pounds was an act of piousness, and via books, VHS tapes, and in-church classes, it made Shamblin a national sensation. Moreover, it allowed her to form the Remnant Fellowship Church, a Brentwood, Tennessee-based religious organization that Zenovich’s exposé revealed to be an insular Christian cult that punished the heavyset, isolated members from friends and relatives, brainwashed children into embracing its Holy Trinity-denying doctrine, oppressed women through misogynistic power structures, and urged parents to abuse and beat their children into obedient submission.

Notable for both her charismatic sermons and her ever-growing hair (which eventually topped out at a remarkable foot-high beehive), Shamblin promoted the notion that splendid things came to those who knelt before God, while bad things were the byproduct of unfaithfulness. Thus, her untimely demise—even more than the prior, sudden death of her granddaughter—was a monumental complication for the church. The Way Down’s second part is curious about how the organization’s leaders will explain this situation to their legions of members, and whether anyone will buy what they’re selling. Yet what it comes up with is more than a bit deflating. Waiting six months before delivering its final two installments was, apparently, not long enough, as director Zenovich offers few insights into the future of Remnant Fellowship Church, whose plans for reconfiguring its doctrine—and hierarchical structure—remain in flux, or at least still largely hidden from public view.

With no exciting bombshells about either the church’s subsequent phase or about the fate of Lara’s former partner Natasha Pavlovich and their daughter, The Way Down shifts its attention to the plane crash itself. Early indications are that Shamblin’s amateur-pilot husband Lara—a former actor who clearly married Shamblin less out of love or devoutness than out of a desire for a wealthy benefactor who’d grant him the high life (and country music career) he craved—was ill equipped to handle the type of plane, and low-visibility weather conditions, he faced on the day of the catastrophe. CGI recreations of the craft’s flight plan, set to Lara’s final radio transmissions, corroborate that theory, although as one official remarks, it’s certainly possible that a technical malfunction could have caused the fatal accident. As with Remnant Fellowship Church’s sustainability, it’s simply too early to tell.

Consequently, The Way Down’s return engagement feels decidedly premature. There are tantalizing intimations that Shamblin’s daughter Elizabeth—seen looking frighteningly skeletal in archival video clips—might not be the heir apparent everyone assumed she’d be, and there’s more predictable news that Elizabeth’s brother Michael (whose relationship with the church was always rocky) has divorced his wife and severed ties with his mom’s empire. For the most part, however, Zenovich seems to have jumped the gun on detailing what’s next for Shamblin’s cult and the many acolytes she nurtured along the way, providing scant revelations that might propel her story forward. These two supplementary episodes feel like addenda that, in most respects, end the saga on an indefinite note, unsure of what Remnant Fellowship Church will look like during its ensuing era—if, that is, it continues to exist at all.

Without much in the way of intriguing developments, The Way Down turns inward for its closing chapter, addressing the way in which Remnant Fellowship Church countered the negative publicity generated by the docuseries’ late-2021 premiere. Even there, though, Zenovich informs us about unsurprising measures taken by Shamblin’s successors—namely, correspondences to HBO that denied all the claims against them, and web sites set up to propagate their self-serving narratives. Naturally, Remnant Fellowship Church didn’t like being outed as a cult that counseled men to keep wives and daughters under their authoritarian thumb; that fully supported child-murdering members Joseph and Sonya Smith, who were convicted of killing their 8-year-old son Josef; and that was run like a money-making venture designed to line the pockets of Shamblin and Lara, who enjoyed the myriad fruits of their followers’ labor. But that was evident before, and The Way Down Part 2 adds little detail or nuance to such ideas.

Most surprising of all is that The Way Down’s second part features interviews with a handful of Remnant survivors who came forward after last fall’s premiere, but barely takes the time to flesh out their stories. Instead, these individuals put more effort into defending themselves against online claims that they’re gullible dupes than they do recounting their harrowing personal ordeals, which is frustrating both because their contentions are less than totally convincing (given the abject nonsense Shamblin peddled), and because they offer nothing that expands our understanding of Remnant Fellowship Church’s day-to-day operations. The most director Zenovich derives from these conversations is that Shamblin was reportedly homophobic as well—hardly the sort of eye-opener that justifies this disappointingly meager follow-up.