Long before a guilty verdict was delivered in the trial of James “Whitey” Bulger, the once-fearsome mob boss had taken on the demeanor of a defeated man. Many observers noted that, as the trial ambled through its final days, Bulger appeared to be shrinking. He and his attorneys, J.W. Carney and Hank Brennan, seemed to become frustrated in their inability to make the case they had hoped to make, and in the end, Bulger quit. He declined to take the stand in his own defense and sat glum for the remainder of the trial, with nary a “fuck you” or “you suck” remaining in his verbal arsenal.

He was found guilty on an array of criminal counts, including racketeering, extortion, money laundering, gun charges, and 11 acts of murder. Another eight murder counts against Bulger were deemed to be “not proven” by the jury of eight men and four women.

As the verdict was read by the head court clerk, at 1:50 pm on Tuesday afternoon, Bulger sat mute, staring straight ahead. For a formerly untouchable gangster whose criminal reign lasted more than 20 years and whose tentacles of power reached into politics through his brother, longtime Massachusetts state Senate president William Bulger, and deep into law enforcement through corrupt associates at virtually every level of the criminal justice system, the verdict was remarkably predictable, even mundane.

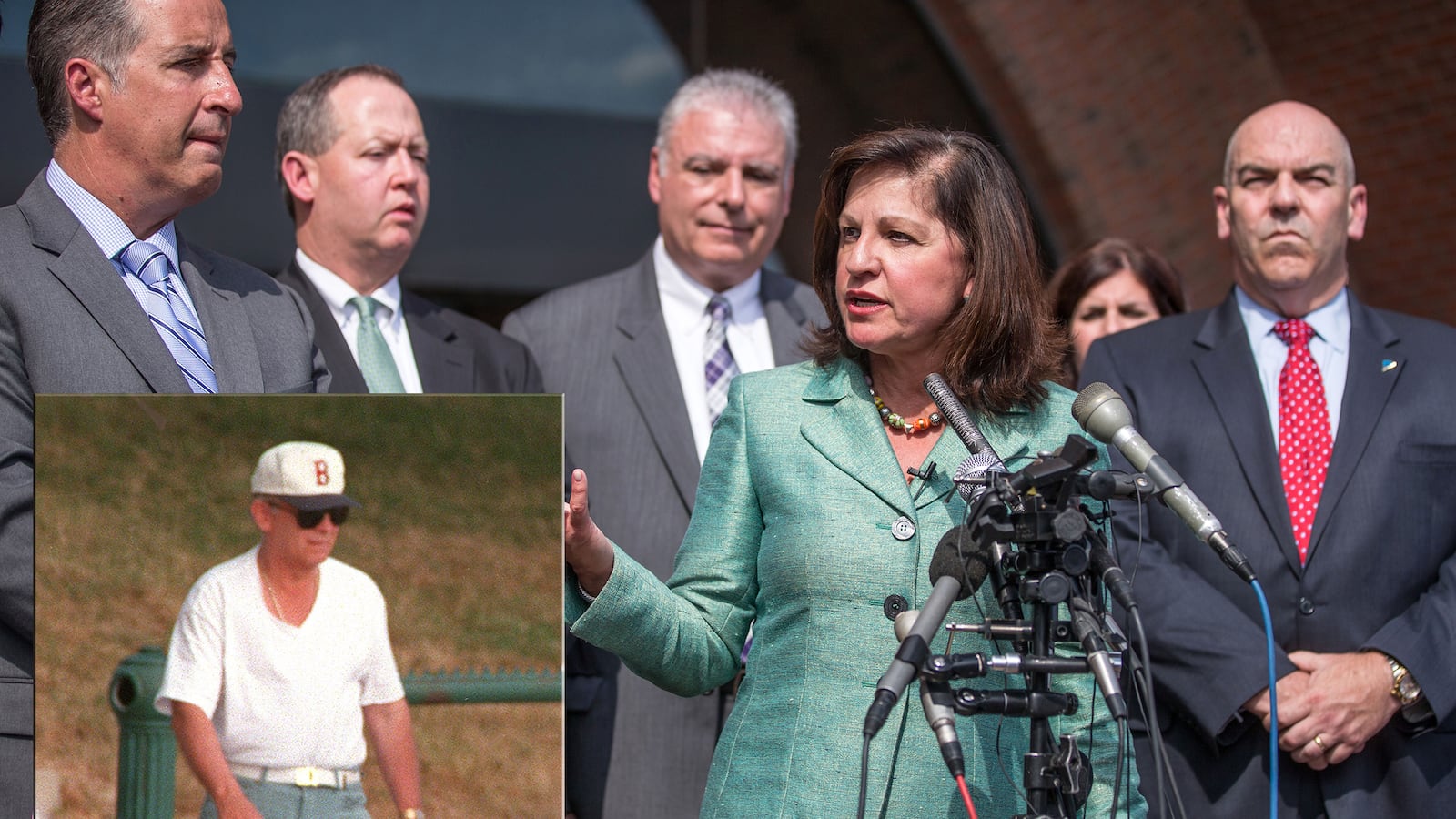

Outside the courtroom after the trial, speaking to the press, the lawyers sought to put a positive spin on a defense strategy that had been doomed almost from the start. “Jay Carney and I showed up in June,” said Brennan. “After looking at this case and working on it for some time, we thought we were going to expose a little bit of government corruption. Little did we think that the government would expose more corruption than we ever could have.”

The statement by Brennan was a non sequitur. In fact, the level of corruption exposed in the trial rarely went beyond what was already known about the Bulger case from previous hearings, trials, and a bookshelf full of tomes on the “unholy alliance” of the Bulger years written by journalists, federal agents, enemies, and former associates of the infamous Whitey.

The prosecution team of Fred Wyshak and Brian Kelly has presided over every Bulger-related trial since Whitey first went on the lam in December 1994. They prosecuted Bulger’s corrupt FBI handler John Connolly on two occasions, with both trials ending in conviction. At both these proceedings Wyshak and Kelly established the “rogue agent” theory that Connolly, acting in consort with his supervisor John Morris and others from the Boston-organized crime unit, was operating as a corrupt virus within the system. The idea that the system itself was corrupt is a concept that Wyshak and Kelly have been seeking to discredit and contain ever since the legendary Wolf hearings in the late-1990s threatened to bring down the entire criminal-justice system in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

In this regard, the current Bulger trial was Wyshak and Kelly’s pièce de résistance.

Aided considerably by Judge Denise Casper, who denied many witnesses proposed by the defense and severely restricted the scope of the trial, Bulger’s fate was sealed before he ever left Plymouth County Correctional Facility, where he was held on 24-hour lockdown, in isolation, with a daily regimen of strip searches and few visitors other than his sycophantic younger brother Jackie Bulger.

Any way you slice it, the evidence was overwhelming. Led by the three main prosecution witnesses—John Martorano, Kevin Weeks, and Steve Flemmi—former gangster associates of Bulger’s who comprised a deadly confederacy of rats, the testimony pertaining to Bulger’s many crimes was gruesome and intimate. The witnesses told tales of how the mob boss terrorized and extorted people by sticking guns in their mouths and machine guns in their groins, how he threatened to cut off their heads. They described how Whitey blew people’s brains out at close range and strangled women to death, then would lie down after the killings as a kind of sexual release. One witness, Steve Flemmi, Bulger’s longtime partner, bitterly described how Whitey used to sit and watch as others were made to dig the graves for their many murder victims. “That’s the way he was,” said Flemmi.

Judging by the verdict, the jury seems to have been appropriately skeptical of testimony delivered by men whose criminal careers were equally as vile as Bulger (one witness, John Martorano, admitted to 20 murders) and who had made plea-bargain deals with the government in exchange for taking the stand. Of the 19 murders Bulger had been charged with, the jury voted “not proven” on any that involved uncorroborated testimony of one witness. In other words, they were unwilling to take the word of any one rat unless there was other evidence to back it up. Along with the rats, there was testimony by extortion victims, family members of murder victims, cops and agents, bookmakers, drug dealers, etc.—virtually a full casting call of the Boston underworld over the last 40 years.

In the face of these insurmountable odds, Carney and Brennan adopted a seemingly novel defense. They conceded that Bulger had been a highly successful racketeer in Boston for decades, that he engaged in illegal gambling, bookmaking, loan sharking, extortion, and drug dealing. But, they said, their client had done so in partnership with a corrupt criminal-justice system. This system facilitated his life of crime and protected him from prosecution. Never once did the defense lawyers say, “therefore you must find my client not guilty.” Rather, their argument seemed to be geared toward a kind of jury nullification strategy, where the jury would concede that Bulger had done the crimes of which he was accused, but if it were to find Bulger guilty it would have to find the entire criminal-justice system guilty.

It was a dubious strategy on many levels, not the least of which was the fact they were denied the opportunity to call witnesses and present evidence that would make such a defense even remotely palatable. In the end, they were left pissing in the wind.

Which raises the question: whatever happened to Whitey’s LSD defense?

For those immersed in the saga of Whitey Bulger, one of the most fascinating biographical details was that back in the 1960s, while Bulger was being held on bank robbery charges at a federal prison in Atlanta, he willingly became a lab rat in a highly covert CIA program called MKULTRA. The purpose of the program was to test the effects of prolonged LSD use on human subjects. Prison inmates were given the option of submitting to the program in exchange for reduced time on their sentences.

Bulger agreed to take part in MKULTRA. He was injected with lysergic acid diethylamide, or LSD-25, nearly every day over a period of 15 months.

The results of the program were often devastating for those who submitted to testing. Some had their brains fried, or they developed personality disorders or committed suicide. In later years, Whitey complained of insomnia, violent nightmares, and severe headaches as a result of his months of acid use. He never again did any kind of hallucinogenic drugs.

Kevin Weeks and Pat Nee, two of Bulger’s associates, both told me in interviews that Bulger had always intended on using his involvement in MKULTRA as a defense if he were ever arrested and charged. In 1979, when the book The Search for the Manchurian Candidate: The CIA and Mind Control by John Marks was published, Bulger read it and was enraged to learn how the covert program had destroyed many lives. According to Weeks, Bulger had even taken preliminary steps to track down the overseer of the program, Dr. Carl Pfeiffer, a diabolical government pharmacologist, and assassinate him.

At the Bulger trial, there was not a single mention of his involvement with MKULTRA. One person who believes it would have made a juicy defense strategy is Anthony Cardinale, a prominent criminal-defense attorney who has represented high-profile mobsters in Boston and New York.

After the defense rested its case but before the verdict was delivered, I sat down with Cardinale at Café Pompeii on Hanover Street in Boston’s Italian North End. Cardinale was highly critical of the defense strategy; he believes they missed a golden opportunity.

“If I defended him,” boasted Cardinale, “I would have got him off. It’s a simple defense. Two parts. A: nearly two years of LSD testing fried his brain. You bring in expert witnesses, psychiatrists, and others who detail the history of how people who took part in this secret CIA program committed suicide or became institutionalized. I’d have had Bulger sit there doodling and drooling. He’s a victim, driven insane by his own government.

“Part B: he returns from prison in the early 1970s and the FBI gets a hold of him. They recruit him as an informant and enable him to the point where he delusionally believes there’s no difference between right and wrong, that he can kill. He believes that it’s OK to do that because the FBI enabled him to the point he insanely believes he had the right to kill people.

“I’m telling you, I could have had a jury feeling sorry for Whitey Bulger. ‘He’s a victim, ladies and gentlemen, and they—the government—are the reason he did all this. He truly believed he could get away with it. He did not know the difference between right and wrong. They put all this in his head. They damaged and manipulated him to the point they turned him into a psychotic killer.”

We will never know if the LSD insanity defense might have worked. What we do know is that the strategy chosen by Bulger’s defense lawyers all but guarantees that the aging mobster will die in prison. By the time he is scheduled to be sentenced, on November 13, he will be 84 years old. Bulger’s lawyers say that he plans to appeal his conviction.