In godfatherly fashion, SEAL Team Six was gearing up to whack Osama Bin Laden at the moment Prince William and Kate Middleton took their vows at Westminster Abbey. The events weren’t connected, but given our culture’s wish to see things through a Hollywood lens, let’s picture President Obama stroking his dog, Bo, behind the Resolute desk and telling the Middletons to “consider this justice a gift on this, the day of your daughter’s wedding.”

Think mixing the government and gangland is farfetched? Going back a few wars, our leaders sent the mob after the Nazis, the subject of my new historical novel, The Devil Himself.

The collaboration between gangsters and Naval intelligence during World War II—which the government denied for nearly 40 years—began after the behemoth cruise ship Normandie caught fire and capsized at Pier 88 in Manhattan on the heels of Pearl Harbor.

The luxury liner was being retrofitted for U.S. troop deployment when it was destroyed in early February 1942. The Navy suspected Nazi sabotage. After all, German U-boats had killed more U.S. sailors in the north Atlantic than died at Pearl Harbor.

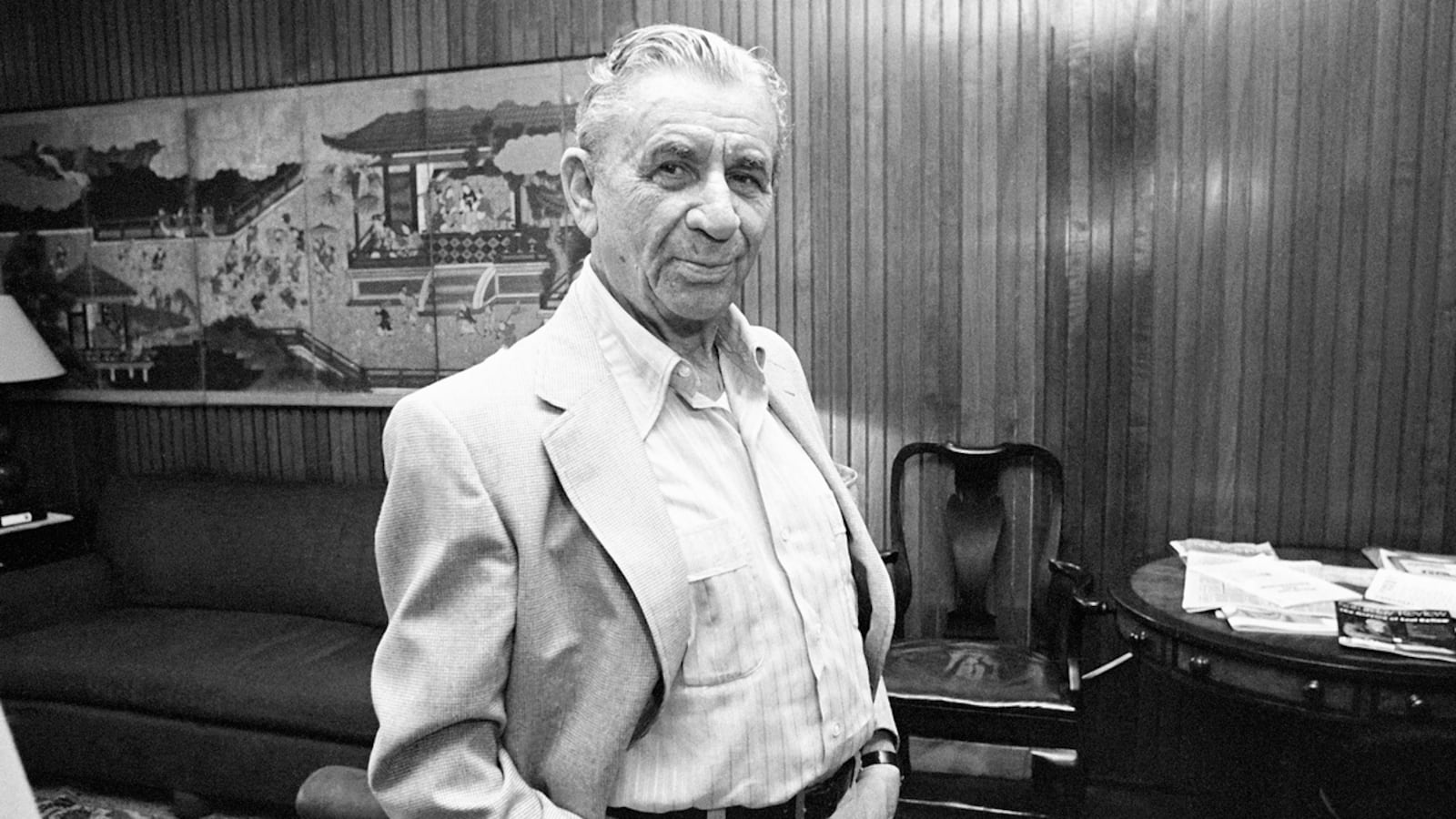

Naval officers were rebuffed by the longshoremen on the mob-controlled New York waterfront, men averse to snitching—for anybody. For help, the Navy turned to mobster Meyer Lansky who, it turns out, had a lot to say in later years about his World War II service, both to family, friends, and in notes he made in a personal journal from Woolworth’s.

Meyer and Teddy Lansky’s granddaughter, Cynthia Duncan, preserved Meyer’s possessions after his death in 1983, and we have been friends for many years. I have opaque memories of my own family elders, who were of Meyer’s generation and mindset. Accordingly, in The Devil Himself, I emphasized what drove a man cut from this rough cloth to join the American war effort.

Our government approached Meyer in part because it knew that he had been waging a campaign of intimidation against domestic Nazi sympathizers, mostly members of the German American Bund.

Horrified by what was happening to his fellow Eastern European Jews, Meyer tried to enlist in the Army, but was rejected because of his age (40) and his height (five-feet-four in socks).

For “Operation Underworld,” Meyer recruited his childhood friend, Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel and Murder, Incorporated’s Louis “Lepke” Buchalter. These Jewish racketeers quickly became the real “inglorious bastards,” using guns, knives and bats to break up Bund rallies and send a message to Nazi sympathizers. As Meyer wryly acknowledged in his notes, “We weren’t yeshiva boys."

In an amazing historical coincidence, President Roosevelt was close to Walter Winchell, the most influential journalist in America, while Winchell’s friend and neighbor in the Majestic House on Central Park West was Meyer Lansky. Winchell was an unapologetic propagandist for the Allied cause and collaborated with gangsters when it suited him. FDR didn’t exactly faint at the rough stuff.

When Nazi saboteurs slithered into the U.S. in the summer of 1942 with plans to blow up railways, chemical plants, and Jewish-owned department stores, mob-controlled union members dropped a dime on the operatives that had checked into Manhattan hotels. We’ll never know what the boys did to the Nazi sympathizers they didn't report to the FBI.

Meyer’s motivations were not entirely pure. In the 1940s, the Jewish rackets were waning in influence as the Italian Mafia expanded. Meyer needed to cement his reputation as an indispensable wizard in the new order.

He approached his Sicilian business partner, the imprisoned Charles “Lucky” Luciano, to lean on Italian racketeers to cooperate with the Navy. Luciano gave the order to his goombahs, who quietly visited him in prison. Luciano provided the Navy with contacts in Sicily to assist Allied invasion planners. In return, Luciano’s 30-50 year prison sentence was commuted. He was deported to Italy, and Meyer’s status as a macher and gambling czar was secure.

There has been much debate over the real value of the Navy-mob collaboration. Surely, the legend that Luciano stormed the shores of Sicily with General Patton to greet a liberated countryside is absurd. But the Lansky/Luciano program did, in fact, guide Allied forces to key Nazi command centers on that beleaguered island.

Domestic waterfront sabotage for the rest of the war was nonexistent. Surely, the newfound cooperation of dockside racketeers had a chilling effect on German espionage. Not even Nazis wanted to stare down Bugsy and Lepke.

My focus in The Devil Himself is Meyer’s existential drama—his urgent passion for assisting his adopted country, a narrative most conducive to historical fiction. Why would he and other mobsters work to defend a country whose government was devoted to putting them behind bars?

Meyer claimed two motives: proving that he was a real American and his sense of dread over the fate of his fellow Eastern European Jews.

It’s hard for our generation to fathom that being accepted as a “real American” was an issue for people who roamed the republic during our lifetimes, but it was. Moreover, the small percentage of Jewish immigrants with racket ties saw crime as a means to an end. No boy of Meyer’s was going to be a gonif, so he proudly sent his son Paul to West Point.

I see Meyer’s wartime service in a modest light befitting his personality: He wanted to serve his country and contributed in the best way he knew how. He neither singlehandedly saved America from the Nazis nor scammed the government with phantom services.

Conspiracy theories aside, the fire that destroyed the Normandie was probably an accident, the result of the military’s frantic mobilization, but it became the catalyst for a heightened campaign of counterespionage that forged a dicey alliance between gangsters and our nation’s defenders. How one feels about such arrangements depends on the usual politics.

Contrary to legend, Meyer did not leave a vast and hidden fortune to his fragmented family. His legacy lives on in the globe’s ubiquitous—and legal—gambling dens, a marketplace he predicted in his private papers, which are displayed at the Las Vegas Mob Experience Museum at the Tropicana Hotel.

Meyer knew he would never be hailed as a patriot, but this didn’t stop him from hocking anyone who would listen that sometimes, when we’re up against foreign hoodlums, we’ve got to make a deal with the devil himself to protect ourselves.