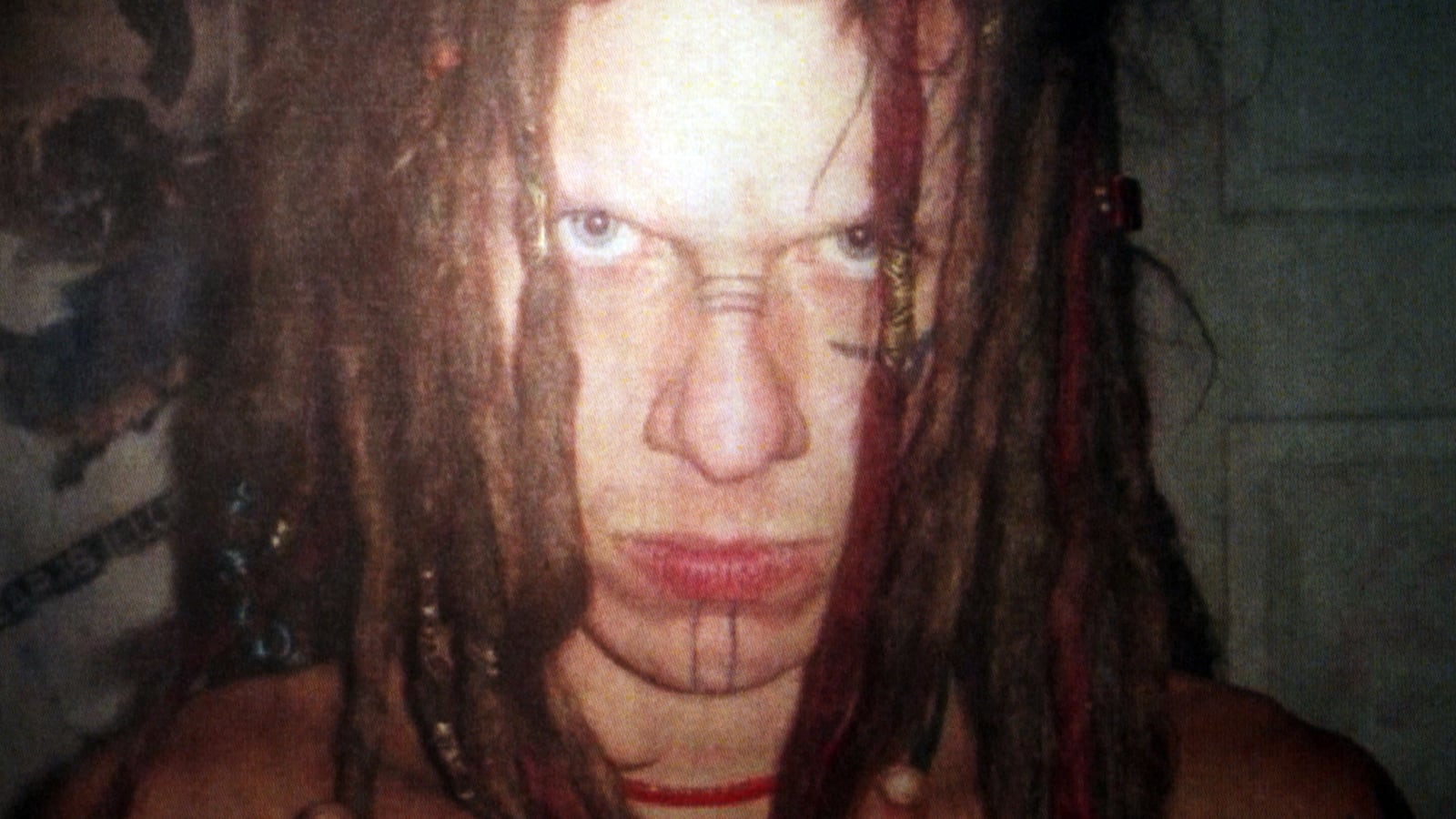

Pazuzu Algarad (real name: John Lawson) was a self-proclaimed Satanist who reveled in extremeness. With a moniker borrowed from The Exorcist, a face covered in tattoos and his teeth sharpened to fine points, Pazuzu spent his days and nights in his Clemmons, North Carolina, home cutting himself and his buddies, drinking the blood of birds, doing copious drugs, performing ritual sacrifices of rabbits, staging nude orgies, and letting people do whatever they pleased to his abode—including popping a squat in the corner of a room, and then leaving the mess to be eaten by one of his many dogs.

“You know, all around having a good time,” as one former friend puts it.

Pazuzu was, it’s safe to say, an unhinged lunatic. But when he began boasting that he had committed murders, and had stored a body in his basement, covered in cat litter and bleach to hide the stench—a tactic that didn’t work, as most attest to the house reeking of filth and death—no one initially took him seriously. Including the cops.

That turned out to be a terrible mistake, as recounted by The Devil You Know, a five-part true-crime series premiering on Viceland Aug. 27. Its story is an inherently sensationalistic one filled with gory tales about Pazuzu’s heavy metal-scored psychosis, which drove him to recruit willing acolytes (including female lovers he donned “fiancées”) into his “fake Charles Manson” cult, and compelled him, post-9/11, to wear Islamic garb and claim Iraqi descent. “He wanted to be the bad guy,” says a former high school classmate, and in that regard, he succeeded, transforming himself from a miserable kid into a nightmarish adult who constructed a mini kingdom of anything-goes mayhem at 2749 Knob Hill Drive, with him as its charismatic king.

Writer/director/producer Patricia E. Gillespie’s miniseries doesn’t skimp on gruesome details—not that doing so would be possible, given how far Pazuzu chose to go in every facet of his life. The Devil You Know, however, wants to be about more than just a shocking case of degradation and murder. Its aim is to cast Pazuzu’s saga as emblematic of larger cultural forces at play in America: the tension between the haves and have-nots; the way mainstream society ignores those falling through the cracks due to economic hardship; and the failings of law enforcement to treat everyone in an equal manner. It’s a noble endeavor, except for the fact that Pazuzu’s case can’t shoulder such weighty significance—not to mention that it’s carried out in a manner that’s more aggravating than enlightening.

Before it begins trying to derive Meaningful Lessons from its material, The Devil You Know proves a riveting case study of a unique madman. Residing with his mother in Clemmons (a suburb of Winston-Salem), Pazuzu lived and breathed his depraved ethos, which was influenced by a combination of horror movies, ‘80s black metal, and Anton LaVey, founder of the Church of Satan. In copious old photographs, Pazuzu appears to be just as scary as his reputation suggested—minus the split tongue that rumors said he gave himself. He routinely bragged about killing people, and in 2010, he and cohort Nicholas Rizzi were charged in connection with the shooting death of an African-American man, Joseph Emmrick Chandler, near the Yadkin River.

Amazingly, Pazuzu didn’t serve any time for Chandler’s death—this despite it appearing like an obvious assassination. More stunning still, by that point, cops had already begun receiving reports about bodies buried in Pazuzu’s backyard. After a first search of the home turned up nothing—a next-to-inconceivable development, given the hoarder-style insanity of the place—Pazuzu’s friend, Iraq war vet Matt Flowers, reported his own suspicions to the cops. A second, more thorough examination of the property followed, and led to the discovery of two bodies: Tommy Dean Welch and Josh Wetzler, the latter of whom had been missing, much to the concern of former girlfriend Stacey Carter (with whom he’d had a young son), for five years.

Pazuzu had killed and buried these men with the help of two fiancées, Amber Burch and Krystal Matlock, and he had dispatched them in the presence of his mother Cynthia, with whom he lived. Those facts, coupled with Pazuzu’s devil worship, attracted national media attention, and The Devil You Know benefits from the participation of many key figures, as well as considerable archival news reports and police footage of the inside of Pazuzu’s house, which lives up to stomach-churning expectations. While there’s an overreliance on soundbite-y comments from talking heads, and its timeline of events isn’t always totally lucid, The Devil You Know conveys the monstrousness of its central figure, and the way he used his maniacal charm to prey upon outcasts looking for both acceptance and permission to lash out at a world that had abandoned them.

Pazuzu Algarad, subject of The Devil You Know.

ViceIn later installments, Gillespie’s show digs into Pazuzu’s backstory, explaining how his crazed behavior was a byproduct of trauma from childhood divorce, severe mental-health problems, and a milieu that—boasting few employment opportunities—left many “bored” and at loose ends. Furthermore, it suggests that local police took far too long to step in and stop Pazuzu, even after receiving multiple tip-offs about his conduct, thanks to good old-fashioned negligence.

Where The Devil You Know stumbles, though, is in trying to go beyond that, via portraits of local blogger Chad Nance and his quest to investigate the Pazuzu case, and Pazuzu compatriots and heroin addicts Nate Anderson and Jenna Woodring. The former spends an inordinate amount of time trying to make Pazuzu an emblematic victim of systemic American failures, which comes across as overreach. Nance also says that he’s being denied “the truth” about what happened to Pazuzu—an assertion that doesn’t jibe with the reasonably comprehensive evidence presented here. His sleuthing-narrator participation contributes to a conspiracy-theory vibe that feels unjustified, especially in light of the fact that justice was, in most respects, eventually served.

Nate and Jenna’s plight, on the other hand, does indicate that parental enabling and neglect is a prime factor in kids’ drugs-and-anarchy behavior. Yet in the end, the couple’s attempts to find smack by any means necessary (including prostitution), along with Matt’s drinking-and-destitution circumstances, receive an undue amount of Intervention-esque attention. Like Chad, they prove increasingly irksome distractions for a series that’s most gripping—and terrifying—when it’s not trying so hard to inflate its story’s importance.