In 1968, art had no problem being big, bold, and sprawling. Jimi Hendrix and the Beatles unleashed gargantuan double album sets that seemed expressly primed for the blowing of minds, and if they didn’t get the synapses firing enough, there was Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey to finish the job. But what we might overlook now, at the distance of some 50 years later, is what is conceivably that year’s best book, a slim volume that is bound to rip the roof off of any head and pour in a whole lot of goodness.

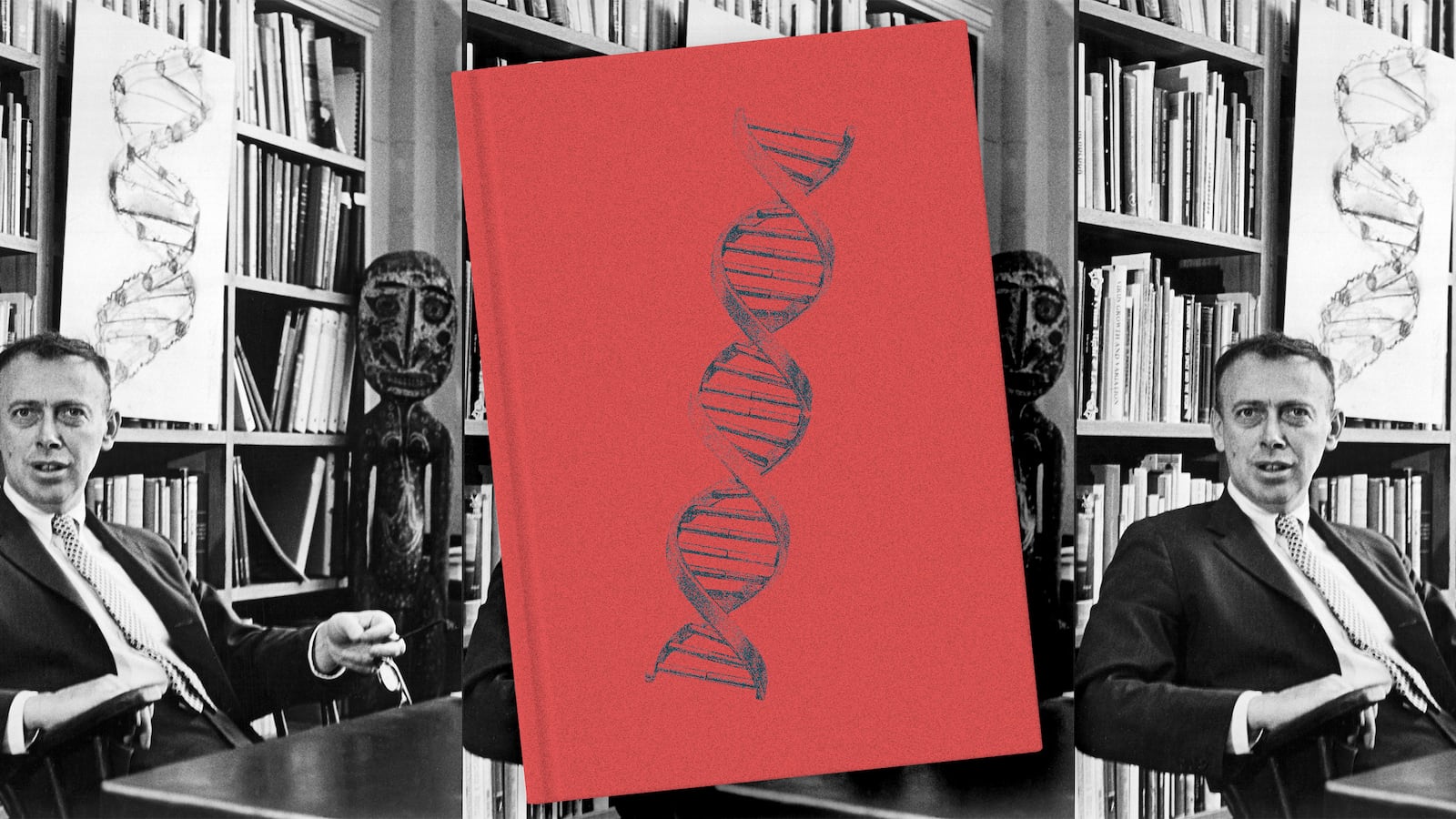

And why is that? Because we’re talking about a book that, oh, I don’t know, explains why we look like we do, why we sound like we do, have the mannerisms we do, possess the health predispositions we come with. Nuts, right? The book in question is The Double Helix: A Personal Account of the Discovery of the Structure of DNA, by James Watson.

There’s a good chance that the last time you heard Watson’s name you were in an eighth grade science class. There was that other fellow—Francis Crick—and the two of them, with a huge assist from Rosalind Franklin, figured out that what makes us us has to do with what’s essentially the root of all chromosomes, this cool looking doodad shaped like two interwoven staircases. You likely discharged the pair of scientists from your mind after a pop quiz or two and had no idea that Watson could write the hell out of a science book.

There can be some hesitation when someone suggests a book that’s far afield from what they normally read. And if it’s science and math? Oh dear. Problems. But what’s fascinating—well, there is a lot that’s fascinating in it—about The Double Helix in particular is what an appropriately human story it is. It reads like a potboiling thriller, a legit page-turner, and we keep reading not just to see how this cognition-altering theory and discovery will play out, but also because science is sometimes no more technical than when you’re helping your kids assemble their bikes.

“I have never seen Francis Crick in a modest mood,” Watson begins, with what is science’s analogue for “Call me Ishmael.” We’re starting mid-scene, with Watson, an American, in England, on account of a grant, something he’s always going to be in search of across these pages so that he can figure out what he wants to do with his scientific life. For, you see, Watson isn’t exactly lighting it up in any field. He’s directionless, which means that when he wants to try a new pursuit, he has to read like crazy to try to get up to speed. Same thing with your life when you’ve had to pivot in business, romance, school.

Meanwhile, there is Crick, the resident nutter at Cambridge University where the two are working together. He is loud and passionate, the kind of guy who when you’re at dinner gets so carried away he might start to cry over something he’s expressed, or pound the table and send the bread crumbs flying as the other guests shoot worried looks in his direction. And he gets pretty juiced when he hits upon a theory that no one else ever has, no matter how ridiculous, and bends any ear he can find for a few hours, before his theory is ultimately disproven and he sets off in search of a new one. And what Crick loves more than anything is figuring out the structures of proteins, what Watson terms “the most complicated of all molecules.”

The book reads like a journal. There’s sadness over the ennui in Watson’s life, the lack of purpose. He’s always worried that he’ll not be up to snuff. He’s sort of friends with Crick, but that’s a challenging prospect. He enjoys England, but it feels like a hideout for him, a way to stay in bed a bit longer rather than face the day, if you will.

We get accounts of the Christmas holiday, beers down at the local, bosses who get pissed and huffy when Watson and Crick start putting forward the latter’s crazy theories. Then we have Rosalind Franklin, who definitely has her stuff together. Watson thinks the world of her mind, and he also thinks she’s kind of hot, while Crick seems somewhat scared of her. But they ultimately need her help, and if you want, you can visit many sources that get into how she might have been squeezed from glory.

This is somewhat like the nonfiction version of the novel Flatland. Or, hell, if you want, the movie Tron. It utterly depends on science, on math, on insider baseball language to some degree, but once the plot is cranking, it never feels like school, and even the lay person can follow along when it gets a trifle tech-y. Because you realize that even Watson, the scientist, is coming to all of this as an outsider, which is heartening, in a way.

They’re trying to solve a puzzle, to figure out a shape, and once they know what the shape is, human understanding is going to be forever altered. One of the bosses gets a ringing ear thanks to Crick’s ceaseless volume, but Crick is the energy driving this operation. He goes home, has his evening meal, sits in his chair trying to watch TV, gets bored, starts brainstorming, and comes charging hard into the office the next day. The duo spends a lot of time fiddling with models, which will please anyone who thinks science is necessarily beyond them. Crick and Watson can be like kids monkeying with Lincoln Logs.

One afternoon Watson is drawing fused rings of adenine on paper when he notices something. The residue of the adenine would form hydrogen bonds, two per residue, that would relate to it by a 180-degree rotation. That would mean two chains, interwoven, held together by hydrogen bonds. Which could be the same premise behind the shape of DNA.

“For over two hours I happily lay awake with pairs of adenine residues whirling in front of my eyes,” he writes. “Only for brief moments did the fear shoot through me that an idea this good could be wrong.”

But it wasn’t. You’d be hard-pressed to come up with a bigger scientific idea in history, and you have to love a story where people full of enthusiasm and doubt—not geniuses for the ages, just very intelligent people working hard—went after something they deemed important, and through smarts and luck figured it out.

The narrative covers the years 1951-53, which puts Watson in his mid-twenties, Crick in his late thirties, but of course this was the moment that would define the lives of both. Everyone since the start of time understood that they would look something like the people who bore them, but the specifics of why—what you might call the shape of why—had eluded everyone that had come before.

It’s pretty damn cool that half a century later we can get lost in a work of literature, sometimes forgetting, despite the enormous stakes, that this is hardcore science. You damn near get paper cuts turning those pages, because while we know whodunit going in, so to speak, the structure of what’s centrally a science-based locked room mystery is beyond piquant: it’s thrilling, it’s human, it’s sprawlingly significant, and it’s the very locus of life. Watson is too under control and self-contained in these pages to say it, but after you read them, you all but hear Crick’s voice in your head demanding, “Beat that!”