During the 1960s, Maurice Bishop was the alias used by an infamous CIA officer in Mexico City, whom conspiracy theorists believe met Lee Harvey Oswald shortly before President John F. Kennedy was murdered in 1963. The alleged meeting is cited as clear evidence that CIA officers were somehow involved in Kennedy’s assassination.

I knew Maurice Bishop, whose real name was David Atlee Phillips. A long time ago, he got me into the agency. I know for certain that the CIA did not kill President Kennedy. Yet Castro’s Secrets: The CIA and Cuba’s Intelligence Machine, a recent book by former CIA analyst Brian Lattell, has taught me many things I did not know about our shadow war against the tiny, communist nation. And it has provided context and overwhelming evidence for many of our intelligence failures vis-à-vis our Cuban counterparts. Namely, that the claims against Phillips and the CIA are the products of a decades-old Cuban disinformation campaign, and that over the past 50 years, Castro has shown himself to be among the greatest spymasters in modern history.

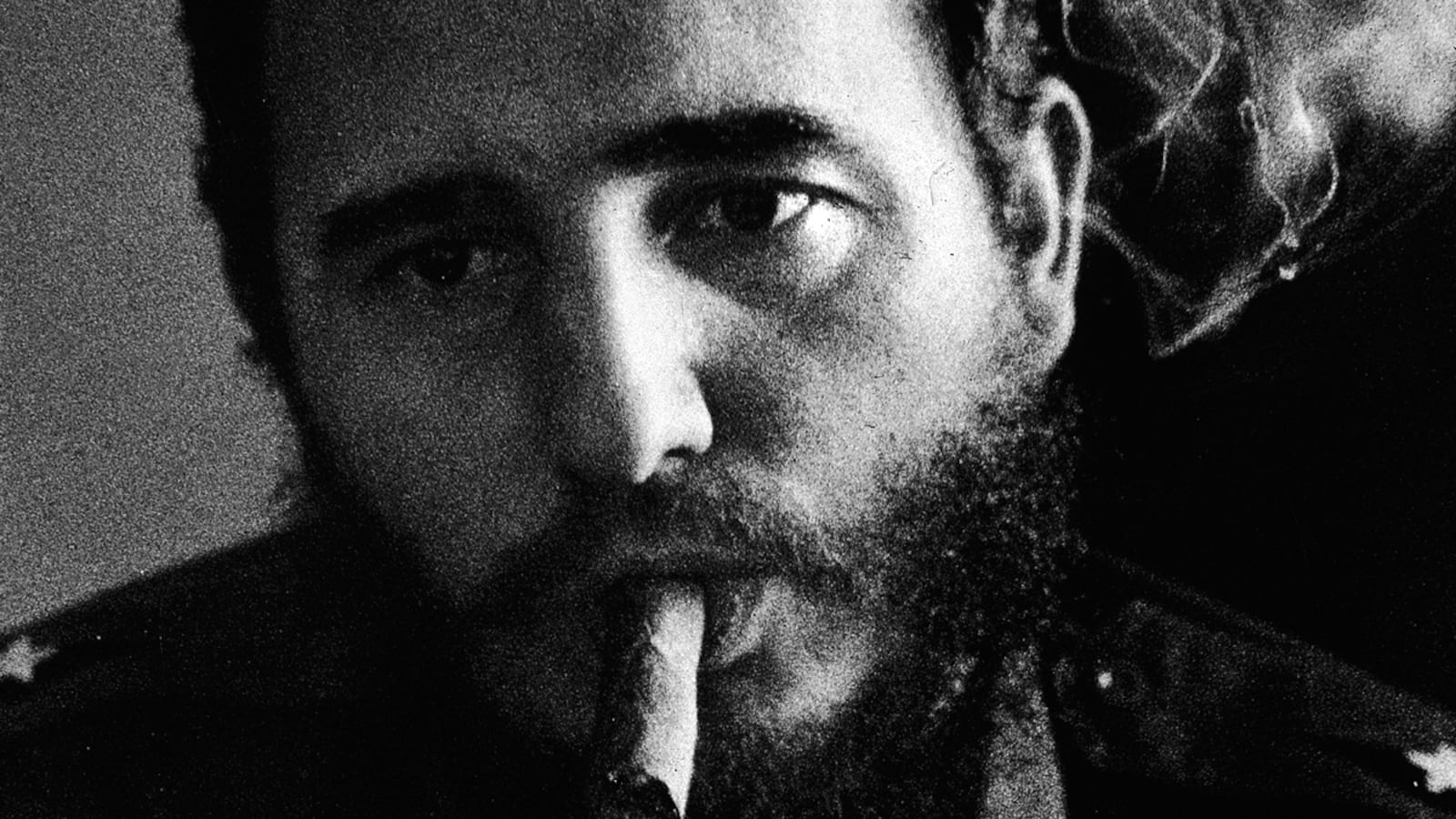

Castro’s Secrets begins like a slow murder mystery then builds damning fact after damning fact into a conclusive, ground-breaking portrait, based on firsthand sources, of how the Cuban strongman—in all his evil brilliance—frequently ran circles around the CIA. Readers who start Lattell’s book with the now widespread image of Castro as a slightly avuncular, foolish caudillo will likely finish it wishing that President Kennedy had followed through during the Bay of Pigs and rid us of this sociopath and his murderous, corrupt regime.

Lattell has the background to write about Castro with authority: he began tracking the Castro brothers for the agency back in the 1960s, finished his career as the U.S. intelligence community’s most senior analyst for Cuban affairs, and now is a senior research associate at the Institute for Cuban and Cuban-American Relations.

The most interesting parts of his narrative revolve around how much Castro knew about the plot to kill Kennedy, and a parallel attempt, on the part of the CIA, to assassinate the Cuban dictator. Lattell delves into this cloak-and-dagger tale through the story of Comandante Rolando Cubela, a senior Cuban military officer who defected to the United States. Yet Lattell alleges that Cubela, a hero of the revolution against Batista, was actually one of Castro’s supreme triumphs, a double agent run so well run that any intelligence officer would admire it.

During the 1960s, the agency knew Cubela by the pseudonym AMLASH, and made him the centerpiece of its supreme assassination plot against Castro. According to Lattell, the CIA trained Cubela to use a special pistol with which to kill Castro from close range. He was then to assume control of the country. The plan had the full backing of the president and was likely set to begin in December 1963, just a month after Kennedy was shot. But Cubela always avoided taking the pistol.

Lattell offers new evidence alleging that Castro personally ran Cubela against the CIA from the start, dangling him in front of the agency in 1961 in Mexico City where Phillips, my eventual mentor, was stationed. Castro even tipped the agency off that he knew all the details, in an effort to convince Americans to back away from their plans. In October 1963, just days after Cubela and his CIA handlers finalized the assassination plot against Castro, the Cuban leader reportedly told a U.S. congressman in Havana: “We don’t trust President Kennedy. We know of the plans the CIA is carrying out.”

Castro also gave multiple public warnings that there would be grave consequences if the Americans continued with their plans: “U.S. leaders should think that if they are aiding terrorist plans to eliminate Cuban leaders, they themselves will not be safe,” he said in early September 1963.

While conspiracy theorists harp on an alleged meeting between Oswald and Phillips, Lattell shows that Castro actually had advance knowledge of Oswald’s desire to kill Kennedy; in fact, he was told of it less than 24 hours after Oswald declared his intentions to Cuban intelligence officers in Mexico City.

Lattell concludes that Castro did not direct Oswald to pull the trigger—only that he did nothing to stop him. But elsewhere in Latin America, he says that Fidel was intimately involved in assassination plots—from sustained efforts to kill Venezuelan President Rómulo Betancourt—Castro’s other bête noire after Kennedy—to the retribution assassinations of almost everyone involved in the killing of Castro’s own darling, Che Guevara.

No one in the CIA who noted Castro’s warnings appeared to take them seriously, or knew of the plot to kill him; apparently, the White House never became aware of the warnings, according to Lattell. Had the importance of Castro’s comments been recognized, a decent counter-intelligence officer should at least have thought twice about the AMLASH operation.

Despite its efforts to kill Castro, the agency never established a way to communicate with Cubela, on the ground in Havana. He frequently talked tough, but did nothing; he had no real links to any military units in Cuba; he continually raised his demands, in the end asking to meet with Attorney General Robert Kennedy before agreeing to take any action. And yet, Lattell says, the CIA pressed on. On Nov. 18, 1963, the agency briefed Kennedy on the AMLASH plans, and received the go-ahead. Three days later, Kennedy was dead. And the Cubela plot withered in the chaotic aftermath of the president’s death.

Years later, the CIA did learn what Castro knew about Oswald, but essentially did nothing with the information; it was apparently too incendiary. As Lattell writes: “Even tentative evidence of a Cuban hand in Kennedy’s death could have sparked a clamoring for punitive action...[so the] story was squirreled away.”

It is possible that the information was considered so extraordinary that lower-level officers didn’t believe it—an institutional blunder that prevented anyone with authority or the proper perspective to pass it on to policymakers; this, too, is typical, as my colleagues and I learned to our chagrin after the September 11 attacks on the World Trade Center.

One of the successes of Castro’s Secrets is that it offers readers a view of both sides of the shadow war. As Jackie Gleason beamed his escapism from Miami Beach to a public focused on the good life, the CIA ran desperate, suicidal raids against Castro, conducted more often than not to show President Kennedy that the agency was doing something than out of any real expectation their plans would work.

There are familiar tales of half-baked assassination attempts and exploding cigars. But as Lattell recounts them, he takes readers past what was previously known and shows that the Kennedy brothers were as single-minded in their efforts to eliminate Castro as he was ruthless and devious.

The Kennedy’s had good reason. During the Cuban missile crisis, Castro was eager for a fight with the U.S., according to Lattell. Though Castro has spent roughly 50 years obfuscating his role—yet another of his disinformation triumphs—Lattell offers convincing evidence that, at the supreme moment of tension during the crisis, it was Castro who ordered the downing of an American U-2 spy plane, not an overly excited local commander.

Likewise, Lattell says, it was Castro who urged Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev to launch a nuclear war against the U.S. in response to the deteriorating situation that the Cuban dictator had engineered. “Castro suggested that in order to prevent our nuclear missiles from being destroyed, we should launch a preemptive strike against the United States,” Lattell writes, quoting Khrushchev’s memoirs, which are backed up by quotes from Cuban defectors and other Russian officials.

One shares the horrified reactions of successive Soviet officials to the man they called their “excitable,” communist ally, who was apparently willing to see us all killed to serve his ego. Only a megalomaniac would vehemently argue for Armageddon so that he could survive in a bunker, the revolutionary hero presiding over an irradiated hemisphere. But then, in Lattell’s account, this is Castro through and through: a sociopath from early manhood, who in the barrios of Havana after World War II, gunned down rivals, shooting them in the back from a distance.

For all his determination, Kennedy failed to kill Castro, not just because the determined loser Oswald shot him, inflecting history, but because before his death, Kennedy’s plans against Castro were based on the overly optimistic assessments of our intelligence community. Yet, the cynicism, delusions, and wishful thinking—all presented as sensible—that plagued the CIA efforts to eliminate Castro were characteristic of several agency operations during my own career decades later (one only has to remember the contra war in Nicaragua in the 1980s and so many of the Bush administration’s actions during the war on terror).

Yet I sympathize with my predecessors: for I experienced the intense pressures from policymakers to solve the problem, when my colleagues and I knew full well that we could offer little but puffed up hopes and demonstrations of aggressive action, while having to downplay our pessimism.

During the mid-1980s, I was spared the misfortune of working Cuban operations. But by the late 1980s, it seems the CIA fared much better in its battles with Castro. The tables had turned. And in the end, it seems that Phillips, my old mentor, maligned as he has been by Cuban disinformation, will have the last laugh. For after reading Castro’s Secrets, no one will be able to think of Fidel as anything but what Lattell shows him to be: a murderer, sociopath, and deluded egomaniac.