I’m not sure exactly where I got it—I think it might have been at an antiques barn in Hawley, Pennsylvania. I do know that I didn’t pay more than three or four bucks for it. It’s a little booklet, about 2 ½ inches by 5 inches, landscape-oriented and printed in garish colors; the process they used for Terry and the Pirates and Flash Gordon comics and such.

How to Make Old Kentucky Famed Drinks, it’s called, in some variant of English. The cover, which shows a tipsy, Col. Sanders doppelgänger and a Whitey McWhite management-trainee in a tux clinking Mint Juleps, ends in a tab with a big hole punched in the middle so you can hang the thing from the neck of a liquor bottle. Well, to be specific, from a bottle of Brown-Forman Kentucky Whisky, whether that’s Old Forester or Old Forman, the two brands the company owned back in 1934 when they published the booklet. (The company wouldn’t buy best-seller Jack Daniel’s for another 22 years.)

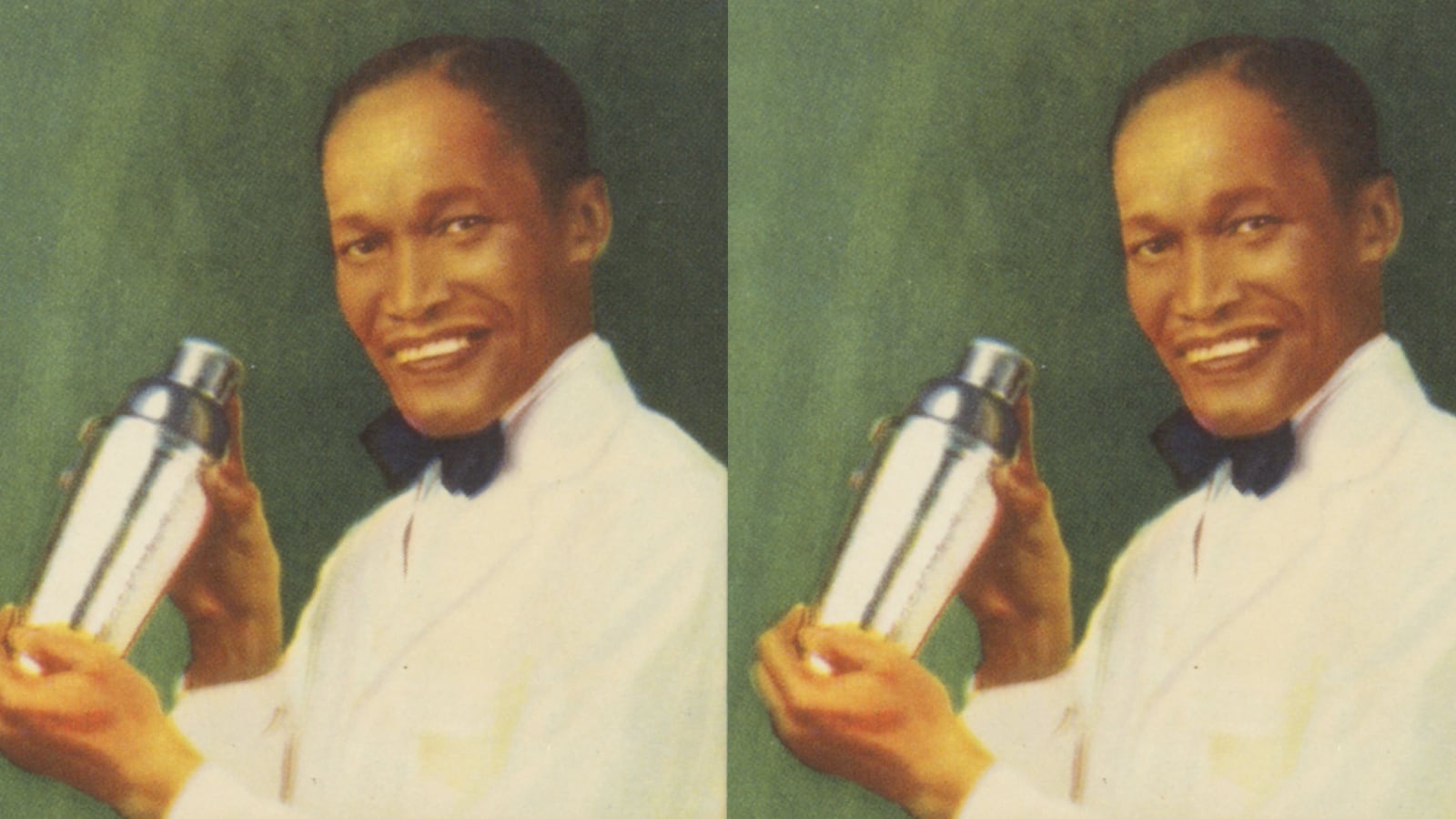

A couple of pages into this piece of vintage liquor-industry ephemera, there’s a photo of a man—a Black man—wielding a silver three-piece cocktail shaker. He’s sporting a clean white jacket and a black bowtie and smiling, maybe a little guardedly. “Prince—Head Bartender, Wynn-Stay Club, Louisville,” the caption reads. On the facing page is “Prince’s own recipe” for the Wynn-Stay Club Whisky Sour, and the following page has the Wynn-Stay Club Whisky Cocktail. And that’s all the information we get about Prince or the Wynn-Stay. No bio, no colorful pull-quote, no club history, not even the man’s last name.

Ok.

Prince Herbert Martin was born in Franklin, Kentucky, on Valentine’s Day, 1895. His father, Felix, was a day laborer and then a house servant, doing well enough at it to raise six children. Some time between Prince’s tenth and 14 birthday his mother died, and soon after he began to get in trouble. In July, 1909, the 14 year old pried open the screen on a local doctor’s window, snuck inside the house and stole $7.65.

He got caught. When Martin was sent to reform school, it was for house-breaking and “incorrigibility,” so this does not appear to have been the first time. He spent at least a year at the Kentucky House of Reform at Greendale, just outside of Lexington. There, he most likely worked on the farm the institution maintained; it’s unlikely that the small, slightly-built boy would have been sent to the rock quarry that it also maintained. Did he avoid the whippings, the leg-chains with 35-pound iron balls or being thrown into “the hole,” all things that Greendale was known for? We don’t know, but he certainly didn’t avoid the particularly squalid housing reserved for Black children (the institution was, of course, segregated). In any case, Martin was probably out by 1913, when he turned 18.

We next see Martin in 1917, when he registered for the draft in Franklin. That same year, he moved to Louisville and got a job as a bellman at the Louisville Country Club.

By 1920, Prince Martin had moved on to the Officer’s Club at Camp (later Fort) Knox, Kentucky’s biggest Army base, where he worked a “checker”—the person who made sure that what was on the waiters’ trays tallied with what was listed on their checks; a position of some responsibility.

Along the way, Martin must have worked a few other positions, too, because in October, 1922, when 75 of the “young college men” of Louisville (as the Louisville Courier-Journal characterized them) got sick of tracking down speakeasies and drinking with riff-raff (okay, here it’s me doing the characterizing) joined together to found the Wynn-Stay Club, Martin was their bartender, caterer, steward and, in fact, sole employee. The Courier-Journal’s piece on the Club’s founding even has a picture of him (unidentified) standing at the back of the ornate club room, surveying it in a proprietary sort of way. (Oh yeah; “Wynn-Stay”? The name of the seat of the Baronets Williams-Wynn in Denbighshire, North Wales. Why? No idea.)

Back in 1922, “college man” meant something rather different from what it means today. College men were fancy; a little bit rich and maybe just a little bit dumb, the way anybody who never really has to scuffle and scratch out a living is a little bit dumb. Unflexed muscles. But no matter. For the next 20 years, Martin mixed their drinks and led their staff, once they got established enough to have one.

By the early 1930s, Prince Martin had clearly become one of Louisville’s reigning mixologists, as our little booklet testifies. (The only other bartender to be included in the pamphlet’s pages was Martin Cuneo of the august Pendennis Club; but let’s save him for another column.) But our man wasn’t content to lurk behind the bar and watch the college men liquorate. As the Courier-Journal put it, by the end of the decade Martin had made his services as caterer and bartender “a ‘must’ at practically every wedding, reception, cocktail party and affair of the socially prominent in Louisville.” His customers ranged from Duchess Marie of Rumania (what she was doing in Louisville I do not know) to Theodore Roosevelt III, whose wedding he catered. That was in early 1940. Two years later, Roosevelt was in the Navy, and a few months later so was Martin.

In fact, Martin seemed to have a special connection to the Navy, or maybe it was just the Wynn-Stay that did: for the 1942 Kentucky Derby—“the first World War II Derby,” the C-J helpfully pointed out—the club hosted a bunch of Navy brass at its annual party, complete with “famed Julep-maker Prince” and his “fragrant drinks.” The paper’s coverage led off with a photo of Martin, looking not entirely gruntled, with a tray of Juleps and some assorted Commodores and whatnot gazing at the creations with appropriate reverence.

In any case, at the end of 1942 the 47-year-old Martin joined the Navy, of his own free will. “I have a home and a good wife,” he told a reporter, “but my country comes first, and so I volunteered.”

In 1942, volunteering for the Navy meant something very different for a Black American than it did for a white one. The Navy was the most segregated branch of the Armed Forces, and that was saying something. If you got land duty, it meant that you would spend the war picking things up—sometimes very dangerous things—and moving them from here to there, supervised by white officers that the Navy judged unfit for sea duty or anything else. If, like Martin, you got sea duty, that meant that you went into the “Messman Branch” as it was known when Martin enlisted, or the “Steward Branch,” as it was renamed in 1943.

Whatever they called it, it was meant as an insult—a branch of the Navy in which white men were not allowed to serve, reserved for African Americans and Asians (mostly Filipinos), with its own ranks, the highest of which was beneath the lowest white Petty Officer, and from which there was no promotion. The only work its members were allowed to do, no matter what their education or aptitude, was to serve meals and to clean up after white officers. Despite the concentrated outcry from the Black press and pressure from the White House, the Navy wouldn’t budge, claiming that it had to do things this way to keep discipline from breaking down. (What if a Black officer gave a white man an order? Couldn’t have that.)

This meant that there would be situations where, say, an A+ physics major from Tuskegee University, who if white would be serving as something like Chief Gunnery Officer, would be ladling out grits to so many coal-shovelers, or a lettered athlete from Morehouse would be standing with a pot of coffee in his hand gazing at the empty seats in the pilots’ mess with the knowledge that, though he would be perfect to fill one, he would never be allowed to do so. Putting aside the moral issues of justice and equity, the sheer waste and inefficiency built into racist systems such as this is always mind-boggling.

By the end of the war, at least, James V. Forrestal, the (civilian) Undersecretary of the Navy, a strong proponent of desegregation, had started cracking open the system; getting Black sailors into places where they could shoot at the enemy and into the schools where the technologies that would define naval warfare going forward were taught; this process accelerated after he became Secretary of the Navy in May, 1944, and especially after he became Secretary of Defense in 1947. The armed forces were finally desegregated in July, 1949, two months after Forrestal’s stress-induced suicide.

When Prince Martin got out of the Navy, in early 1946, he returned to Louisville and took a job as maitre d’ at the Old House, a new and very fancy restaurant in downtown Louisville. Unlike many veterans of the Steward Branch, Martin was intensely proud of his service; indeed, at the Old House he posted a large, autographed photo of his old officer on the wall, along with letters conveying his “high regard and a ‘well done’” for Martin’s service.

In fact, Martin’s position was the opposite of our hypothetical Morehouse man’s. When he enlisted, he entered the Messman Branch as a “Chief Officer’s Steward,” the third-highest rank in the branch, and was quickly promoted to Chief Steward, the highest. Martin had come into the branch not as someone whose potential was being ignored, but rather as one of the country’s top experts in the very thing the branch was supposed to be doing. What’s more, he didn’t spend the war bussing tables or tonging over pork-chops to young college men in officers’ uniforms. He only looked after one officer, and the last time that officer had been in Naval uniform was during World War I. Martin was in fact James Forrestal’s “special attaché”: his personal steward; his Jeeves. Indeed, it seems likely that he had been recruited specially for that position.

As such, we have to assume that Martin accompanied the Undersecretary on his tours of the combat zones of the South Pacific; that he, too, was at Kwajalein and Iwo Jima.

When ships are in war zones, everybody on board runs the same risks. Being Black didn’t prevent Cook Third Class Dorie Miller from going down with the escort carrier Liscome Bay when it was torpedoed in 1943. But neither had it prevented him from saving the lives of several of his shipmates, including the Captain, when the battleship West Virginia was sunk at Pearl Harbor two years before, or from standing on the bridge of the sinking ship and wielding an antiaircraft machine gun, for which he had no training (or, according to the Navy, aptitude), to shoot down a pair of Japanese bombers. Miller earned the Navy Cross that day, the first Black sailor to be awarded one.

Prince Martin’s service wasn’t so dramatic, but it was still worthy, although if he could cater Teddy Roosevelt III’s wedding he could also manage the food service on a battleship, and if he could do that he could just as well run the gunnery department. But nonetheless, still worthy. There is a folder of letters between him and Forrestal among the latter’s papers, held at Princeton University. The archives are closed due to covid, but I would love to see what they say; to see if they show that his daily contact and conversations with Martin helped Forrestal in his drive to desegregate the Navy. (You know they talked—Martin was a master bartender, and that’s what bartenders do.)

Who knows, maybe Martin was Forrestal’s secret weapon in his struggle to drag the Navy into the nuclear age: Martin knew those people, the ones holding things back; he had spent 20 years cooling them off. Did he step into Forrestal’s Washington office with a strategic tray of Juleps every now and then?

Even more, though, I would love to consult the Prince Herbert Martin Papers; to pore over his recipes and reminiscences; see what he saw and meet whom he met.

Unfortunately, Princeton doesn’t have those, and neither does the University of Kentucky or, as far as I know, anyone else. All we really have is a small handful of newspaper articles, three or four photographs where Martin looks like if you started him talking he just might tell you everything he knows (as musician Sonny Boy Williamson used to say), and that Brown-Forman neck-hanger. Bartenders’ lives—even white bartenders’ lives—tend to be lived in real time, not on the page.

We more or less lose track of Martin after 1949 until 1965, when he was admitted to the local VA hospital for esophageal cancer and died three days later. He was still a “waiter” at his death, which is how he had always listed his occupation, and was living with his wife in the same little house he’d been in since 1950 or so, on the west side of town where his back window would have had a nice view of the huge Old Forester bottle that serves as the Brown-Forman distillery’s water tower. His grave, in Louisville’s Eastern Cemetery, is marked with a serviceman’s cross.

INGREDIENTS

- 2 oz Good bourbon, such as Old Forester Bonded

- .5 oz Lemon juice

- 1 tsp Sugar

- 2 dashes Orange bitters

- Lemon peel twist

- Glass: Rocks

- Garnish: Cherry

DIRECTIONS

In a rocks glass, stir the sugar into the lemon juice. Fill the glass with cracked ice, add the whiskey and bitters, and stir well. Twist the lemon peel over the top, rub it around the rim of the glass and then discard it. Garnish with a cherry if you like cherries.

INGREDIENTS

- 1.5 oz Good bourbon, such as Old Forester Bonded

- .75 oz Sweet vermouth

- .5 oz Lemon juice

- .25 oz Grenadine

- 2 dashes Orange bitters

- Glass: Cocktail

- Garnish: Cherry

DIRECTIONS

Add all the ingredients to a shaker and fill with ice. Shake, and strain into a chilled cocktail glass. Garnish with a cherry if you like cherries.