In the shameful time before the Emancipation Proclamation, P.T. Barnum took a first step toward becoming America’s premiere showman with the $1,000 purchase of an elderly African-American woman whose owner had been exhibiting her as the 161-year-old wet nurse of George Washington.

“The Greatest Natural and National Curiosity in the World!” Barnum’s posters proclaimed.

The accompanying ad copy said the woman was named Joice Heth, was “the slave of Augustine Washington, (the father of Gen. Washington,)” and “was the first person who put clothes on the unconscious infant, who, in after days, led our heroic fathers on to glory, to victory, and freedom.”

When the novelty wore off and ticket sales for the traveling curiosity declined, Barnum planted an anonymous letter in a Boston newspaper saying that it was all “a humbug,” but the truth was “vastly more interesting.”

“What purports to be a remarkably old woman is simply a curiously constructed automaton,” the letter said.

Ticket tales soared amidst a public debate whether the woman was what another planted letter termed “a fake or a fake fake.” Barnum made an added score after the woman died by selling 1,500 tickets to a public autopsy in a New York saloon.

Barnum’s subsequent ventures included Juba, an astonishingly talented dancer in the “break down” style, melding African dance with Irish step dancing. The problem was that Juba was black in a time when theaters would only permit white performers. Barnum fitted him with a bad wig and rubbed charcoal on his face and Juba became the first black man to appear as a white man in blackface.

Juba went off on his own after being written up by Charles Dickens in his chronicle of a New York visit. Barnum had a brush with bankruptcy and wrote a book of his own called The Art of Money Getting. He went on a lecture tour, advising others on how to make their fortune. His own fortune came after he mounted an “elephantine expedition” to Sir Lanka that brought back nine elephants.

The eventual result was what Barnum billed as “The Greatest Show on Earth.” Other showmen had even bigger herds, but nobody was better than Barnum at generating publicity and excitement. Barnum was assisted by Richard “Tody” Hamilton, who bragged he had “grabbed more space for nothing than anyone you know” and was described by The New York Times as “the greatest press agent who ever lived.” The Times noted that Hamilton had “never been known to tell a lie when the truth would do as well.” Hamilton made a point of never actually seeing a show he promoted.

“He would not allow his conception of it to be distracted by contact with the details,” the Times reported.

When Barnum’s health was faltering in early April of 1891, Hamilton contrived to revive him by spreading a bit of fake news, informing the press that the legendary showman had died. Barnum rebounded as he read his own obituaries the next morning, complete with pictures.

“It revived him after oxygen failed,” the Times reported. “His physicians agreed that the premature obituary had prolonged his life.”

Even so, the effect was transitory, and four days later, the newspaper prepared another round of obituaries after confirming that Barnum really had died. A rival had tauntingly noted some time before that Barnum had no heir. Barnum had countered that whereas the other showman was sure to slip into obscurity, The Greatest Show on Earth was sure to live on.

“Strength and profit for generations!” Barnum exclaimed.

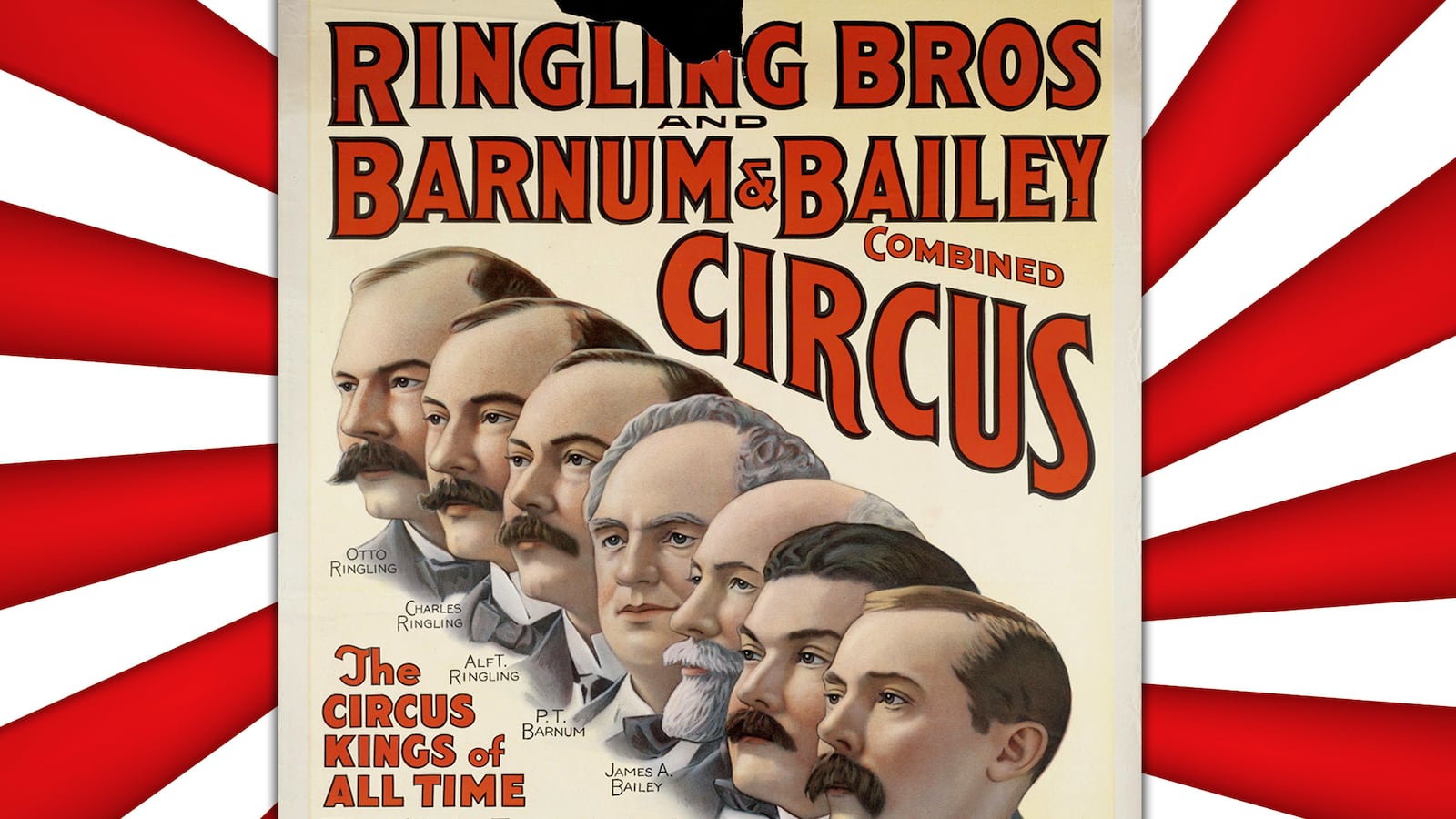

Indeed it did, and Barnum’s name along with it long after his demise. He had partnered with James Bailey, who continued to give Barnum top billing. The show was purchased by the Ringling Brothers after Bailey’s death, likely from a tiny insect bite on the nose that became infected, seen by some as karma for a control freak who had ordered the execution of at least seven elephants who failed to do as bid. The circus continued on as Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey’s Greatest Show on Earth.

But last week came word that this will be the show’s final season. The end was presaged in part in 1897, when the Ringling Brothers Circus – founded by five brothers of that name – became the first show to pair the Big Top with a “black tent” that used an Edison Vitascope to show moving images of boxing champion James “Gentleman Jim” Corbett in action, along with other films “more for the entertainment of the ladies.” Movies and television came to supplant circuses as sources of entertainment, but the Greatest Show survived and might have continued were it not for a dark truth that Barnum and Hamilton were no longer around to dispel.

Back when the cruel treatment of elephants first became a public issue, Barnum persuaded ASPCA founder Henry Bergh that the creatures’ thick skin prevented them from feeling pain when they were beaten and prodded with a “bull hook.” Never mind that the hooks could only work if they hurt. Never mind how gently elephants nuzzle each other, stroking their fellow creatures’ supposedly insensitive skin.

And anyway, Barnum made it known – falsely it would later prove - that he had a provision in his will to build a monument to Bergh.

The bull hooks got smaller over the years, but fact outlasted fiction and in 2015, the show announced that it would be phasing out elephants. They remained the heart of what makes a circus a circus and last week the Greatest Show on Earth announced that it will cease to be a show at all, giving its last performances in May.

The Barnum name will go with it, but the legacy of the showman who started out with the supposed wet nurse of our first president can be seen in the inauguration of our next president at the end of the week.

Where Barnum hawked The Art of Money Getting, Donald Trump hawked The Art of the Deal. And Trump has proven as adept as were Barnum and Hamilton when it comes to getting free media attention. Trump has also been equally ready to put forth a lie when the truth does not do as well.

No doubt Barnum would have smiled on witnessing Trump’s fake fake news.

And Trump’s series of rallies certainly had the feel of a traveling circus.

And what Trump does with Twitter is much like what Barnum did when papering towns with leaflets slamming the competition.

Yet, there can be no doubt that Barnum would have ultimately denounced Trump.

After touring with the fake 161-year-old wet nurse turned fake fake automaton and the black dancer in black face, Barnum also made a foray into politics, successfully running as a Republican for the Connecticut State Legislature in 1865.

“It always seemed to me that a man who ‘takes no interest in politics’ is unfit to live in a land where the government rests in the hands of people,” he later wrote.

Unlike many in elective office, the self-proclaimed “Prince of Humbug” set humbug aside in favor of not just the truth, but actual higher truths. The man who had once essentially purchased “George Washington’s nurse” became a leading voice in favor of black suffrage, declaring that “without regard to color or condition, all men are equally children of the common Father.”

“A human soul, ‘that God has created and Christ died for,’ is not to be trifled with,” Barnum proclaimed. “It may tenant the body of a Chinaman, a Turk, an Arab or a Hottentot—it is still an immortal spirit.”

In his own particular soul, Barnum was a showman and he may have surprised even himself when he proved to be before all else a devout believer in American democracy. He refrained from a showman’s tricks when he ran as the party of Lincoln’s local candidate for U.S. Congress. He lost to a cousin who would go on to become chairman of the Democratic National Committee and a U.S. Senator.

In the meantime, Barnum formed what would soon be billed as “The Greatest Show on Earth” and would continue until this year. We could have used the diversion as we now enter the era of Trump, who seems not to understand that humbug is fine for a show and money getting, but has no place at all when it comes to sacred business of The Greatest Democracy on Earth.