I was working late that cold December night on a report to be broadcast the following morning. As news director of a popular Long Island radio station, WLIR, I did a daily feature on whatever subjects might be of interest to our young, rock music-oriented audience. The topic that night was gun control, and I was editing the words of CNN commentator Dr. Michael Halberstam, who had spoken out forcefully the previous week in favor of stricter laws governing firearms. In an incident as ironic as it was tragic, Halberstam was fatally shot in his home by an intruder days after his commentary aired, and I was using the unfortunate coincidence to point out just how eerily prophetic the doctor’s dire warnings were.

As I was completing the report, one of the station’s student interns burst into the studio, red-faced and breathless. “They just said on TV someone was shot outside the Dakota building, and that it might be John Lennon,” he yelled. I raced to the newsroom, grabbed an AP wire with the same sketchy information, told the disc jockey to turn on the microphone in my news booth, and broadcast the bulletin.

Now on auto-pilot, I returned to the newsroom, desperately dialed the Dakota’s police precinct, and managed to get through to a sergeant who provided more details on the shooting, but could not confirm the fate or identity of the victim. He told me it would be OK to call back again shortly.

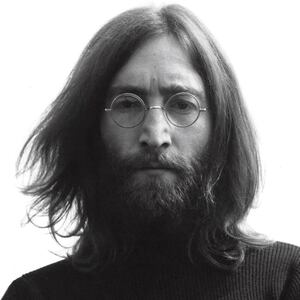

Fans mark the anniversary of musician John Lennon's death with a makeshift memorial at Strawberry Fields in Central Park December 8, 2003, in New York City.

Matthew Peyton/GettyI went on the air, telling our listeners what I knew. As the local, then national airwaves exploded with speculation, I again reached the same helpful sergeant, who said, on tape, that the victim was tentatively identified as Lennon, he was in serious condition, and the gunman had been apprehended. Off-air, however, he confirmed to me that it was the former Beatle.

At 11:32 p.m., about 40 minutes after the shooting, I broadcast the update. Fifteen minutes later, I called the sergeant back. This time he said, calmly but with some hesitation, “Well, they’re about to make the announcement, so I guess it’s OK to tell you now that it was Lennon, and that he’s dead."

I gasped, slammed the news booth door shut and gestured for the DJ, Bob Waugh, to stop the music and open my mic. I repeated what the cop had just told me, thereby becoming the first—according to many who were monitoring various radio and TV stations that night—to confirm the death of John Lennon.

In the chaos of the moment, I had not thought to record myself making the announcement. The following day, however, a listener called, said he’d recorded it off the air, and would send me a cassette. That never happened, and despite my best efforts, I never found a recording of it—until this year.

A decade ago, another WLIR colleague, Ben Manilla, had been given a CD containing some of his reports from 1980. Ben did not listen to the entire CD until several months ago—at which point he heard, at the very end, my report with an update on Lennon’s condition, followed by my announcement of his death. Ben immediately shared it with me, and hearing it nearly 40 years later literally sent a chill down my spine.

After the words left my mouth, I looked at the stunned face of my colleague, then realized that I literally could not speak. I think in that choking, adrenaline-filled moment, the enormity of what had just happened not only to Lennon, but to every member of my generation, suddenly dawned on me. My mind was jolted back to the morning in January 1964, when my radio clicked on and I heard the sweet sounds of “I Want to Hold Your Hand” for the first time. I was nearly 11 years old, and I clearly remember my instantaneous reaction: “I LOVE this, and my parents are gonna HATE it!” I recalled the raucous Ed Sullivan shows, my sister’s treasured Beatles trading-card collection, and the day I was crossing Broadway and bumped into a white stretch limo stuck in traffic, carrying John and Yoko. My friends and I waved excitedly to them, and they smiled and waved back.

But here I was now in a news booth, speechless after having just announced the death of an icon. Bob, in shock, mumbled a few words, then played whatever record was cued up on his turntable. About 10 minutes later, shortly after midnight, the announcement was made at Roosevelt Hospital, the official word crossed the AP, UPI and Reuters wires, and the world heard the astonishing news.

The rest of that long night is a blur. We aired Beatles and Lennon music nonstop, and hundreds of listeners called or came to the station to express and share their profound shock and grief. I conducted telephone interviews with anyone I could find who knew the man: musicians such as Billy Joel; pop culture historians; the director of the Sullivan programs; movie critic Rex Reed, who lived in the Dakota and described the Lennons as unfailingly “kind, thoughtful, and polite” neighbors; and Geraldo Rivera, whose friendship with the controversial couple led to their final live concert: a benefit for the developmentally disabled.

Around daybreak, I broadcast my unexpectedly timely report on gun control, and told the audience that what had occurred on West 72nd Street should be unacceptable in a civilized society. I noted that Lennon had spent the latter part of his life pointing out what was wrong with the world; the circumstances of his death sadly reinforced his message.

With all the accumulated wisdom of my 27 years, I also solemnly informed my listeners that no one would ever again be able to listen to Beatles music in the same way, with the same joy. The killer had stolen that from us, as he had robbed Lennon’s life from him. For a new generation of music lovers, and probably for most of my peers as well, my prediction has not held. But for me, it’s been true. In the 40 years since his murder, I have never once heard John Lennon’s voice without thinking of that awful night, and how a superbly talented man of peace was taken from us by a cruel and still incomprehensible act of violence.