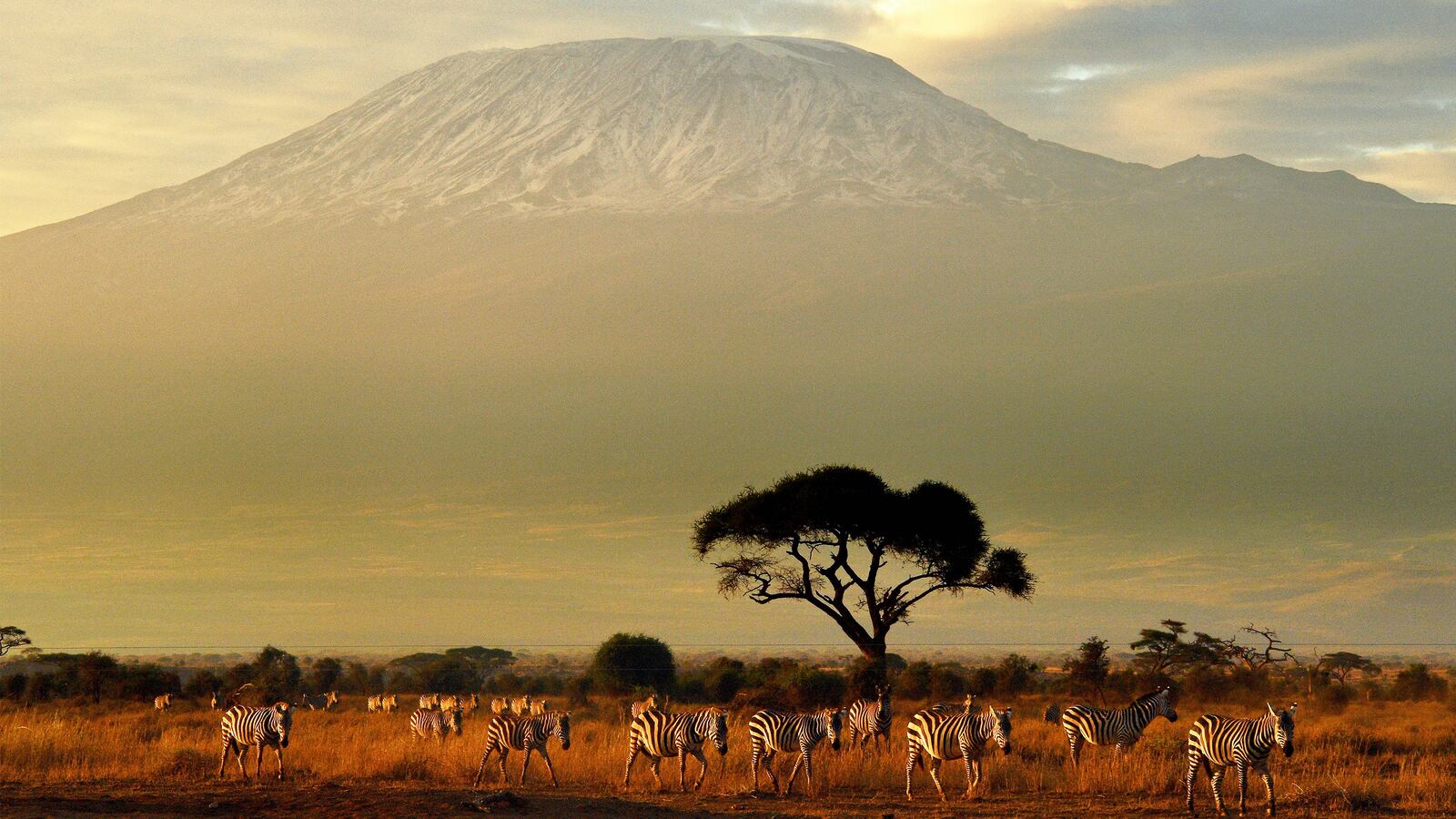

The first time I almost died I was six months old. We had just moved to Kenya and were living in a small green house far out in the middle of the grasslands in Amboseli National Park, close enough to the border with Tanzania to see Mount Kilimanjaro. My mother put me down to sleep in my crib with a candle burning on the windowsill since I screamed if the room was completely dark. As the story goes, when she came back a little while later to see if I had fallen asleep, she found me no longer alone in my room but suddenly in the company of a very large, very angry black mamba.

My mother froze. There wasn’t anything she could do. She couldn’t run into the room without scaring the snake into biting me, so she stood in the doorway, hoping the snake would decide that the flailing baby was too disruptive and leave on its own, which it eventually did, but only after I made an especially loud “coo!” and attempted to grab it by the neck.

I don’t remember the incident with the snake, of course, nor do I remember the second time I almost died, a few months later when my parents sat me down to play in the grass in front of our house only to see me immediately swarmed by siafus, or safari ants.

“So what did you do?” I asked, years later when I first heard the story. Siafu bites are very painful, and our Maasai housekeeper Masaku used to tell me how siafus could kill and eat small animals and had jaws so strong that the Maasai sometimes used them for stitches when they had an injury. I couldn’t imagine a baby surviving being swarmed by them. Mom looked uncomfortable.

“Well, we got them off you, of course,” she said. “Dad brushed most of them off and then we got the rest of them to let go of you by dunking you in the rain barrel behind the house.”

“You dunked me in a rain barrel?” I yelled.

“Of course we did! I mean, it was no big deal,” Mom said. “Obviously you were fine. It was a lot less scary than the first time you met a baboon.”

Wild Life: Dispatches from a Childhood of Baboons and Button-Downs

That one I do remember. I must have been three or so and was again playing outside the house in Kenya. I’d walked a short way down the dusty road that led away from our house and toward the nearby Maasai village, following elephant tracks. I wasn’t paying attention to anything around me, just kicking one of the round balls of elephant poop that the other village children and I often used as soccer balls. I squatted down in the road to pick it up when I heard a rustle in the grass behind me and turned around to find a gigantic monkey standing over me.

Even as a small child I knew it was a baboon. The monkeys Mom and Dad studied were much smaller and had black spots on their faces; they were called vervet monkeys, though I’d always called them “fever monkeys” since it was easier to say. The vervets rarely came close to our house, but the baboons were often nearby; Masaku told me these nyani were garbage animals that came into his village to look for food. It was the job of the little boys in the village to chase them away from the cows and goats since, though the nyani were monkeys, they were skilled hunters and often killed baby goats and ate them. I knew this particular baboon was a male because his snout was wider and heavier than the females’ and Dad said the male baboons were about the size of a Saint Bernard, whatever that was.

I dropped my ball of elephant poop and stared up at the baboon, which didn’t seem all that scary. I smiled at it. Mom always told me that animals aren’t dangerous by nature; they’re dangerous if you startle them, and if you don’t then you’re just another animal to them. Then the baboon grunted and took a few steps closer to me. “Keena,” I heard Dad say quietly from the front steps of the house where he’d been watching me play. “I need you to do something for me.”

“Okay!” I said brightly, still looking at the baboon.

“I need you to walk backward to me. Do you think you can do that?”

“Yes, Daddy!” I said. I waved to the baboon and began walking backward through the soft sand in the road. As I retreated, the baboon immediately sat down and snatched up my soccer ball, happily picking through it for partially digested seeds and fruits. Fresh elephant poop is one of their favorite foods.

It didn’t occur to me that the baboon was any danger to me. Dad seemed relieved when he finally picked me up, but didn’t raise his voice or shout in any way that made me think he’d been worried for my safety. Baboons were familiar, and just as much a part of my daily life as the Maasai warriors who trooped down the road singing songs in their bright red shukas or the herds of elephants, buffalo, and zebras that roamed through the grassland around our house, which Dad drove me out to see in our Land Rover if I’d been good.

We’d been living in Kenya for almost two years by then, all in the little green house in the grasslands under the mountain. I knew that Kenya was in Africa, and Africa was a long way away from another place called America, where Mom and Dad said we had another home that I didn’t remember. “Home” to me meant soft wind and waving grass, the smell of zebras and the whooping of hyenas as the sun set over the plains. Home was our housekeeper Masaku letting me tenderize meat with an empty wine bottle before dinner and shaking out my shoes before putting them on in case scorpions or spiders were inside. Home was spending my days wrenching the lug nuts on and off the wheels of our truck and going on game drives with Dad to look at buffalo and watch quietly as they moved through the grasslands like ships on the sea.

From Wild Life: Dispatches from a Childhood of Baboons and Button-Downs by Keena Roberts Copyright © 2019 by the author and reprinted with permission of Grand Central Publishing. All rights reserved.