There’s always a little bit of a connection between Oklahoma City and me. When the basketball team, the Oklahoma City Thunder, wins, I get, like, 50 texts.

I’m currently in Brighton, England, but on Monday, I was at a hotel right in the middle of London on Camden Street. We were playing a show here and I had the flu, so I had been sleeping all day Monday. My phone was lying there on the bed and I started getting hundreds of texts. After I woke up from whatever cold medicine I was on, it was around 10 p.m. in London, so 4 p.m. in Oklahoma City. I turned on the news and watched. As the night went on, you don’t know if you’re going to hear from someone who says, “Oh my god” this-and-that, and you do your best to check in on people as quickly as you can. That’s the marvel of cellphones, I guess.

In fact, the top news story over here in London was the Oklahoma City tornado. Reports said up to 75 people were dead because of a storm—and I say storm because all the other top news stories from around the world involved a lot of people dead, but from bombs and people hating each other. The only slight comfort is that these were just good people trying to go to school and go to work, and the universe comes down on them. All the other news stories were this horrible but petty man-versus-man thing. Even though the city suffered a tragedy, I’m still standing tall and thinking, “Yeah. That’s our people.”

My sister lives in Moore, close enough to Plaza Towers Elementary School to think, “Oh my god, there’s kids just down the road from me who are trapped in there.” Her own daughter was not at that school but a nearby school, and it went on lockdown. My sister, her husband, mother-in-law, and pets all jumped into their shelter. You can try to imagine what they went through: Their daughter’s at a school, they’re in their tornado shelter, and you know the tornado’s there and you don’t know what’s going to happen. And then you come out of the shelter, and you’re still separated. They’re all OK and their home didn’t suffer any damage. Thankfully, there’s nobody that I’m deeply connected with who’s going through a lot of pain right now.

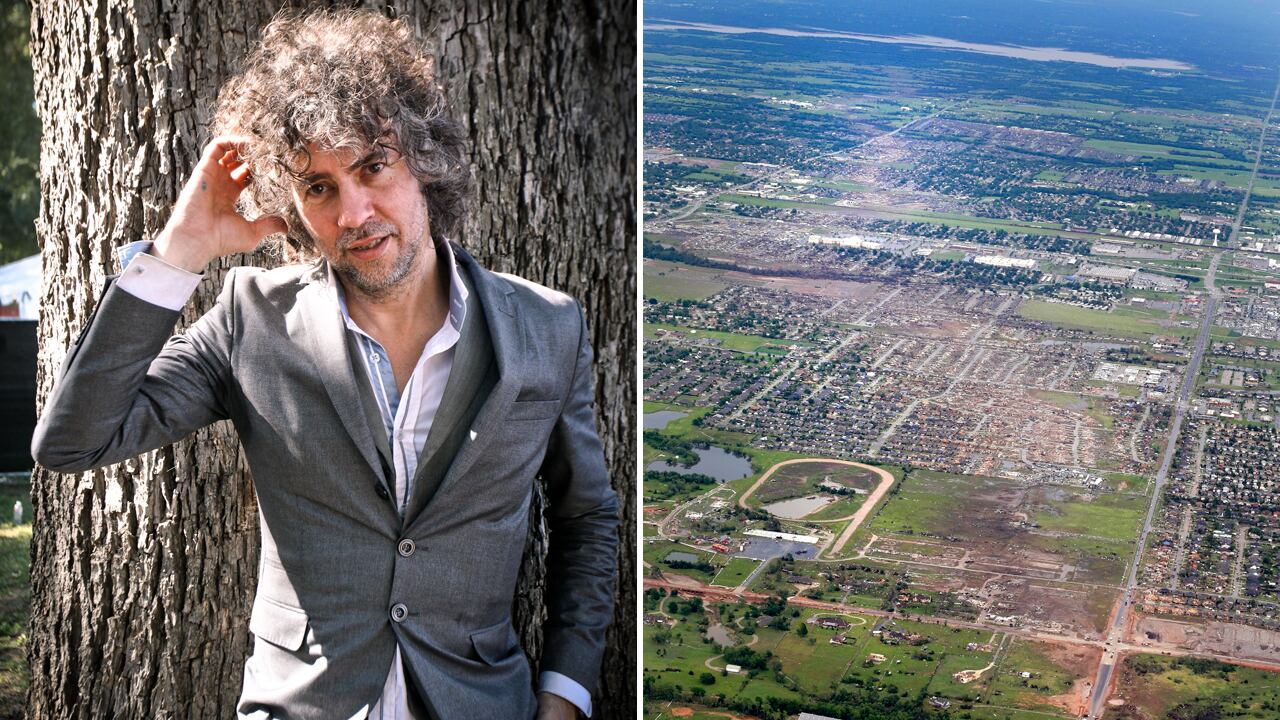

I live in Oklahoma City and Plaza Towers Elementary School is in Moore, so it’s close. I know where the damage is. It’s on the highway between Oklahoma City and Norman, Oklahoma, which we go to a lot—Moore is right in between there. You look over there, and things that you’ve seen for years are now just a pile of rubble.

Some of my really good friends also grew up in Moore. There’s a little center of town that’s based along the highway there that’s taken a beating over the years, but in the past five or six years, they’ve really taken to the highway part of it. I heard that the Warren Theater is one of the places where many of the victims and their families have taken shelter. It’s one of these giant multiplexes where you can drink beer and have dinner while you watch the newest 3-D movie. It’s quite full all the time. You drive by there and can’t believe 600 people are there on a Monday night watching a movie.

The Flaming Lips’ only memory of Moore, and this doesn’t speak for the city, is when we had some of our guitars and things stolen in Moore and we then noticed how many pawn shops you could go to there. I do know one joke. They say, “Of all the cities between Washington, D.C., and New York City, there’s Moore between Oklahoma City and Norman.”

The storm that went through Oklahoma City in 1999, for what it’s worth, was pretty big news and we were again in England at the time. I think more people died in that one. I’ve lived in Oklahoma City since 1961, and you’ve had a gradual sense of this tornado technology. When we were younger, people would say “tornado warning” and everyone would go underground within a 100-mile radius because you had no idea where the fuck it was. The technology has gotten to where people track it and know where it is. Not to be casual about it, but you can be on your way to a hardware store and a tornado could be hitting on the other side of town and you can think, “No big deal.” But once it hits and you know people are involved, then you know it’s a big deal and that there will be a great deal of commotion and people will need help. It’s an interesting thing that Mother Nature does.

When we were younger, you’d take tornadoes seriously because it’s this giant force. You would hardly have time to get going. The tornado sirens would go and then my parents would huddle us all in our storm shelter in the middle of the house. You’d go in there for quite a long time, and then the storm would go. It would be scary. Then you’d drive around after and see the destruction. I don’t remember any tornadoes prior to 1999 taking too many lives. You’d drive around and see a car in a tree and go, “Wow,” but it wouldn’t occur to you that kids who went to school with you were no longer there. That didn’t happen in my experience. Now there are many more people living in the areas where tornadoes go. If a tornado goes off in the middle of the desert, no one really cares. That area is called Tornado Alley, and you can live there if you want, but the storm technology has allowed people to live there without much fear or regret. People think, “Well, this house is a good house, we can afford it, and even though it’s in an area that some people might think is dangerous, the weathermen will tell us what to do, and we’ll do it, and better to live here in a house that we like than somewhere else in a house that we don’t like.” The technology allows you to live in that area, and you can live there a long, long time and nothing can happen, and then one day, you’re at work, your kids are at school, and a storm comes. It’s a strange million-to-one risk. And I’d say the risk is worth taking. People just get so used to it.

But I never thought about leaving Oklahoma City. We formed the music group the Flaming Lips, and that’s where we lived. The thought of let’s move somewhere else and try to be a more successful group never occurred to us. That’s not the kind of group we were. I think the Flaming Lips being from Oklahoma City kind of made us cool, and it’s not something we’ve ever tried to shake off. Oklahoma City is a real “get up and go to work”–type of place, and I think a lot of people have attributed that to our group. And we’d go to places in England and Europe, and they’d all remark about how we’re all from Oklahoma City. It’s not something that we commanded, but it was great that people thought it was cool we were from there. And I’m into my family and I wanted to live with them. Before we knew it, we were able to get a house and a big place to rehearse there. As a group, we never even considered we’d leave. Our music was in our heads, and we were going to make it in our house.

I think the people of Oklahoma City are resilient, but I think it always happens in communities—people have the desire to help. They have a sense that even though you may not know each other, we’re all one. I saw this happen in Boston, too, because I have friends there. If you’re even a person sitting at home, you’re compelled to do something. People forget that you could donate $10 to the Red Cross, and that’s all you need to do. If you could do that, that’s a beautiful way to help.

But we can always help each other, and it shouldn’t always take a tragedy to make us realize this. If you can’t help the people of Moore, see how the people on your street are doing.

As told to Marlow Stern.