If there’s one constant in the lives of artists, it’s this: it’s damn hard to be a budding creative. From the Renaissance to the contemporary “isms”, art has evolved at the hands of young, brilliant minds struggling to express new ideas and experiment with cutting-edge techniques…all while finding a way to pay those pesky bills.

Even Michelangelo—one of the most important artists to touch chisel to marble or paint brush to ceiling—wasn’t immune to this predicament. But, he was a genius. So naturally, he came up with a genius scheme to help gain some monetary relief early in his career. In short, the great Michelangelo became a forger.

In 1496, Michelangelo Buonarroti was a 21-year-old Florentine transplant to Rome. His life had been thrown into turmoil over the previous four years after his patron, Lorenzo de Medici, succumbed to old age in 1492. With the death of the most powerful man in Florence, the city found itself victim to a tide of political unrest.

Having lost his patron and, for a time, his home city, which was no longer safe for Medici acolytes, Michelangelo found himself moving around Italy, fighting for recognition and attention from deep-pocketed buyers. It wasn’t just his lack of a household name that caused him to embody the role of “struggling artist.” In another historical constant that repeats century after century, most wealthy Italians were more interested in “antiques” and the “classics” than the newfangled creations of upstarts like Michelangelo.

In late 15th-century Italy, ancient Roman sculptures were the coveted status symbols of the day.

Facing these difficulties, Michelangelo set about sculpting the piece that would become known as “Sleeping Cupid.” He designed the new work as a copy of the Roman antiques that were in vogue at the time, possibly using a classic Cupid that resided in the Medici Gardens as his model.

In Giorgio Vasari’s momentous 1550 tome The Lives of Artists, the author recounts the story of the finished sculpture being shown to Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco, who observed, “If you were to bury it under ground and then sent it to Rome treated in such a manner as to make it look old, I am certain that it would pass for an antique, and you would thus obtain much more for it than by selling it here."

According to Vasari, accounts differ on what happened after this pronouncement. Some say Michelangelo took the advice to heart and aged his creation himself; others that he consigned the statue to the art dealer Baldassari del Milanese, who buried “Sleeping Cupid” in the acidic soil of his vineyard to force the premature aging. Regardless of who did the deed, Milanese sold the finished sculpture to Cardinal Raffaele Riario as an authentic ancient Roman sculpture. The con had succeeded.

Well, at least it did at first.

Riario soon developed doubts about his newest prized possession. Here, too, there are differing accounts as to how he made this duplicitous discovery and unmasked the culprit. A 2005 article in the Renaissance Quarterly contends that Riario became suspicious that his ancient work may have been a product of contemporary Florence, so he sent an agent to the northern city to investigate. “During their encounter, Michelangelo mentioned the Cupid among his recent works and furnished further proof of his artistic virtuosity by drawing a hand of exceptional grace,” Deborah Parker writes in the piece.

By contrast, a 1923 account in the Boston Daily Globe cites a story told by Rafael Sabatini in The Life of Cesare Borgia that places Michelangelo in Rome in 1498, two years after the creation of “Sleeping Cupid.”

Sabatini’s story contends that Michelangelo visited Riario’s home to offer his letter of recommendation upon arriving in the city. In an attempt to impress and intimidate the young artist, the cardinal proceeded to take him on a tour of his personal art gallery.

“If the cardinal meant to use the young Florentine cavalierly, his punishment was immediate and poetic, for amid the antiques Michelangelo beheld a sleeping Cupid which he instantly claimed as his own work,” Sabatini wrote in his 1912 book.

However, the con was discovered, and it wasn’t the only case of fraud perpetrated during the original transaction. Michelangelo soon learned that, while Milanese had given him 30 ducats as the purported sale price of “Sleeping Cupid,” Riario had actually paid the dealer 200 ducats for the piece. Michelangelo had been shorted 170 ducats.

But the joke was ultimately on Milanese, who was blamed for the nefarious deal and forced to pay the cardinal back. Michelangelo, on the other hand, kept his paltry earnings, gained an admirer and patron in Riario, and was rewarded for his efforts with a major career boost.

“Indeed, having successfully passed off his work as a Roman marble helped add luster to the start of a glistening career, by showing Michelangelo had the technical skill and creative genius to match his forebears,” Noah Charney writes in The Art of Forgery.

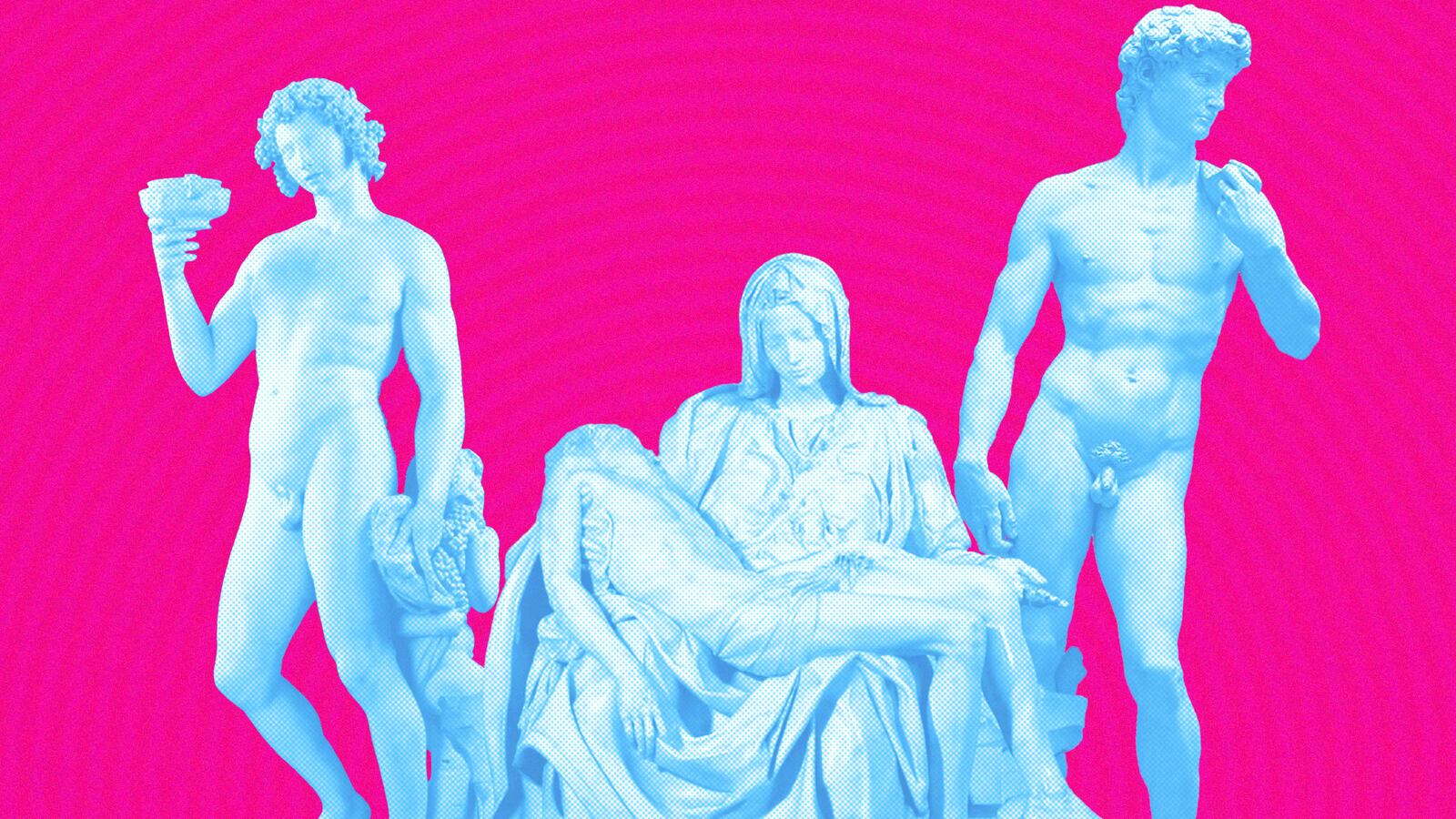

Michelangelo’s career quickly skyrocketed. He carved the renowned “Bacchus” shortly after finishing “Sleeping Cupid,” and the “Pieta” followed two years later.

Five years after he set about creating a forgery, the artist would receive the commission to create the David, and seven years after that, he would find find himself lying on scaffolding, arm extended towards the ceiling, beginning his historic work on the Sistine Chapel.

The “Sleeping Cupid,” for its part, only survives in the stories passed down through the centuries of the great artist Michelangelo. After being forced to issue a refund to the cardinal, Milanese regained possession of the statue. By this time, the artist was a bit more famous, so Milanese quickly re-sold the piece—as a genuine Michelangelo.

The sculpture would continue to change prestigious hands many more times after that until, most scholars believe, it ended up in the possession of King Charles I in the Whitehall Palace in London, where it was destroyed in a fire in 1698.

And that’s where Michelangelo’s infamous forging career ended. Or did it?

One of the problems with being known as such a competent—if one-time—forger is that it casts the faintest shadow of a doubt over settling this part of his career as “case closed.”

Historians claim “Sleeping Cupid,” was Michelangelo’s one and only romp on the dark side. But according to Atlas Obscura, questions have arisen regarding whether the famous Greek statue “Laocoon and his Sons” may also be his handiwork. After all, the artist is known to have made sketches similar to the masterpiece, and he officially helped to restore (or “restore”) the piece after it was discovered…on the property of one of his friends.

Maybe, just maybe, the ingenious Michelangelo continues to laugh at us from beyond the grave.