Sometime last year, I riffed on the Korean soft tofu and kimchi stew called kimchi soondubu, and found a dish that I loved. It was quick and comforting, and we ate it a lot, probably once a week, and then we snapped. We didn’t need any more of that dish. It’s over.

Coming into the end of an extended year of what was, for most of us, relentless cooking, even the most enthusiastic cooks have worn down some grooves. Like lots of folks, I didn’t go anywhere—no palate cleansing week at the beach, no campfire grits with cane syrup, no flat of Mount Hood cherries eaten in the rental car.

A good cookbook can step into this breach, because a good cookbook feels like someone else is taking over for a while. It’s a pleasant feeling—I like listening to what someone else has to say about food. I want to have the way I think about flavor and technique nudged around a little.

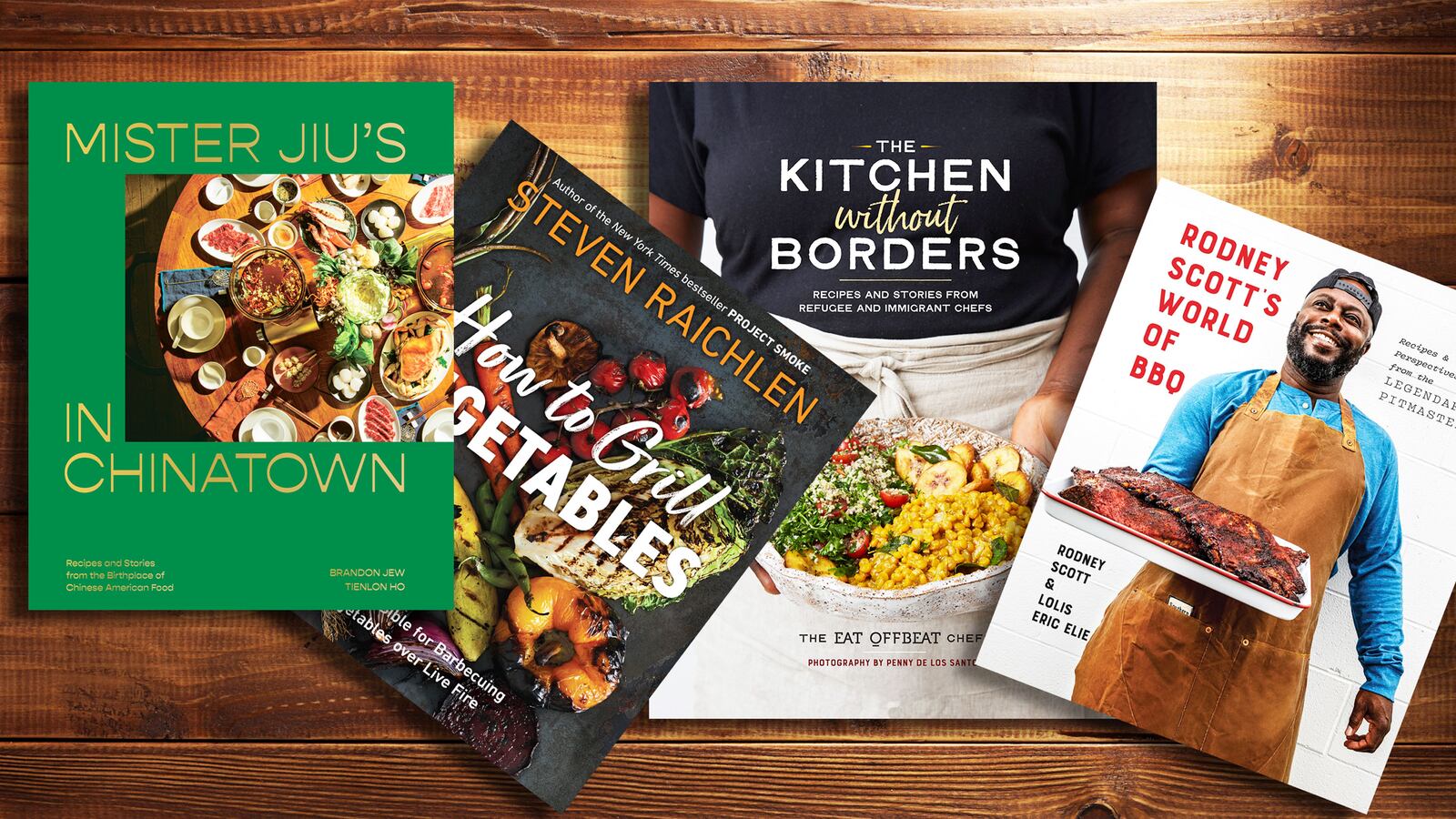

Here are four recently published books that did the job:

Mister Jiu’s in Chinatown is a formal and beautiful book from Brandon Jew, who is the chef and owner of the Michelin starred Mr. Jiu’s in San Francisco. It includes Pete Lee’s gorgeous and inspiring photographs that evoke an entire world—street scenes and stacked crab traps, glimpses through Chinatown windows, and what I like most: lots and lots of hands, lots of process, tons of knife work. Much of the food in these pages is being eaten, being offered or being made, and that reins in the exuberance of Jew’s cuisine and brings it to the table.

That is not at all to say that some of the food in Mister Jiu’s isn’t aspirational—there are monster dishes in here. They sound and look fantastic, but one had better set aside some time before embarking on the Pig Trotter Ham Sui Got or the White-Cut Chicken Galantine. On the other hand, I cannot wait for my tomatoes to come in, so I can make his Mouthwatering Tomatoes and Liang Fen, in which blanched and skinned tomatoes and torn leaves of basil are served over fat, cool mung bean noodles, drizzled with chili oil and dusted with a blend of peppercorns.

Jew worked with writer Tienlon Ho to deliver insight into the history of his recipes. The riff which precedes his recipe for Asparagus, Olives and Smoked Doufu is an inspired bridge between the flavor of Italian oil cured olives and fermented black beans. The essay on prawn toast swerves through Victor Bergeron’s menu at Trader Vic’s, Chinese American cookery and the “American dinner-party schtick” of fondue and rumaki. It all comes together to make a beautiful disc of mousse on soft milk bread, without collapsing into any sort of nonsense about authenticity or purity. It’s gorgeous and intelligent.

Authenticity does have its place, and that place is in Rodney Scott’s much anticipated cookbook, which contains the secrets to what makes every day a good day at his whole hog barbecue restaurants in Charleston, South Carolina, and Birmingham, Alabama. In Rodney Scott’s World of BBQ, I believe Scott has set down the final word in backyard pig cookery. A stack of cinder blocks and a fire to the side seems like a pretty straightforward project, but hours upon hours are spent discussing the set up, and I would not be at all surprised to learn that friendships have been lost arguing about how many courses of cinder blocks are required or how many runs of rebar need to go across it. If you are inclined to cook a whole pig at any point in your life (and I hope you are) I suggest you skip the arguments, skip the web searches and go right to Scott’s book

.

Scott has an interesting story to tell—his path is a winding one—and Lolis Eric Elie helped him get it all down on paper. And if the combination of pork rinds and chocolate cake sounds interesting, Scott’s got your number. Again, the headliner of this book is not something you’re going to have on the regular, but the standards are there as well, with solid recipes for ribs, greens, coleslaw and a fine punch. For anyone who thinks about barbecue and its permutations, Scott’s contribution to the conversation is necessary.

Steven Raichlen, the man by the grill on Public Television, has a new cookbook whose unassuming title, How to Grill Vegetables, does nothing to express the sheer abundance of what’s contained inside. I admit that I looked askance at this book for quite some time before digging in, thinking, that I knew exactly how to grill vegetables. Reader—I did not.

“Raichlen’s Rule states that if something tastes great baked, fried, or sautéed, it probably tastes better grilled,” and he certainly lives by this credo. For instance there is a recipe for cedar planked eggplant parmigiana, which is exactly the sort of thing that makes me think I didn’t actually know how to grill vegetables at all.

But generally Raichlen is celebratory about flavor and dismissive of rules. There’s a miso bagna cauda and Brussels sprouts, bacon and date kebabs. There’s even ashes in the vinaigrette. The grilled leeks with ash vinaigrette is, in fact, worth the price of admission. Inspired by José Andrés by way of Ferran Adrià, it seems like something you shouldn’t be able to pull off at home, but it is, and the results are fantastic. I’m going to drizzle charred vinaigrette on a lot of stuff this summer.

Eat Offbeat, a catering company in New York, which hires talented refugees and showcases their cuisines, recently published The Kitchen Without Borders. The book’s publisher, Workman, is giving two percent of the cover price of every copy sold to the International Rescue Committee. One needn’t, however, fall back on charitable instincts. The book is more than a smorgasbord—it’s like a World’s Fair international food pavilion bound between covers. The ethos is charming.

Siblings Manal and Wissam Kahi, who started Eat Offbeat, begin the book with their Syrian grandmother’s recipe for hummus and then celebrate the individual dishes of different cooks from around the world. “As we remember dishes that are significant to us, it’s not perfection, but imperfection that makes them special and memorable. It’s the hint of extra garlic that reminds of our grandmother’s unique touch or the extra sauce that makes us recognize, without any doubt, our mother’s recipe.”

Inside the cookbook, you’ll find things somewhat familiar, such as Vegetarian Biryani, and novel (at least to me), such as Rooz, a basmati rice cooked with chickpeas and tuna, with a crispy potato bottom that is flipped out of the pan in the way one flips tahdig.

My favorite recipes here are dishes that twist familiar things just a little, such as the petite dumplings called momos from Nepal, or the Persian frittata kuku sabzi in which 10 cups of herbs are packed into six beaten eggs. Riz gras from Guinea, a chicken, cabbage and rice stew, felt familiar to me, while also being fresh. And fattoush changes just enough about a summer salad (pomegranate molasses sumac and crisped pita slivers) to make it something wholly new.

A little comfort found in something wholly new is perfect for this summer. That’s exactly what I was looking for.