Should an African-American preacher’s cry in 1843 to his enslaved brothers and sisters “Resist, resist, RESIST! …. Use all means” even “If you must bleed”—be remembered today as brave and prescient or forgotten as marginal and radical; too Malcolm X, not Martin Luther King enough?

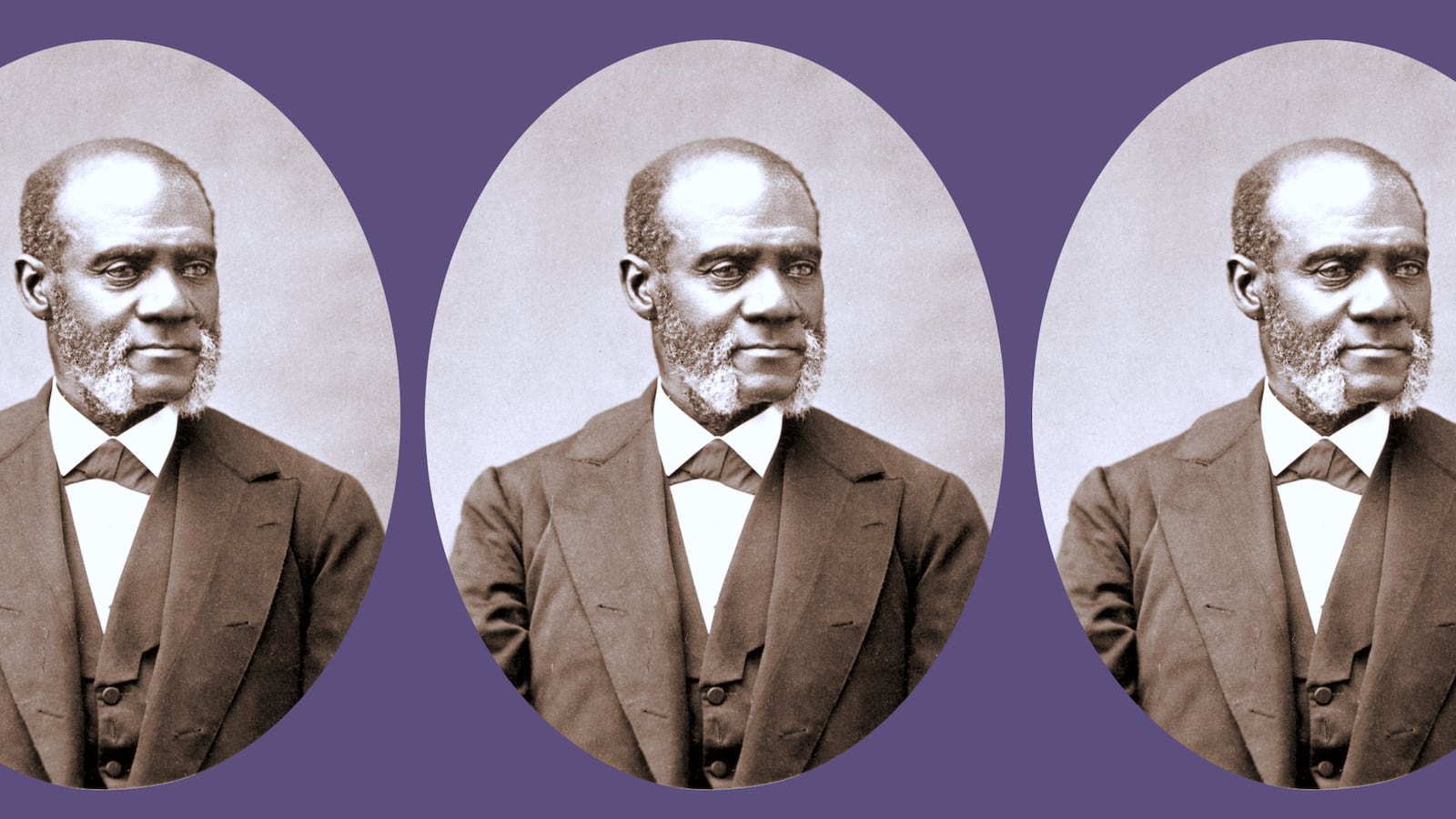

So far, the popular verdict is clear. Fifty years after Martin Luther King’s death, his phrases are already immortal. Yet 175 years after his stirring speech—and a lifetime of courageous, eloquent, advocacy—the Reverend Henry Highland Garnet is forgotten. Reinforcing the judgment is the ongoing reverence for Garnet’s moderate rival, Frederick Douglass.

Although forged in revolution, Americans like their revolutionaries with powdered wigs and frocked coats, with top hats and “malice toward none,” with suit jackets and dreams we all “have.” It’s actually America’s strength. Slavery’s foul legacy is burdensome enough. We’re proud we had no Robespierrean guillotines or Stalinesque purges. But clearly, America’s Revolution of landowners and slaveowners fell short. In his “Address to the Slaves of the United States,” stirring seventy delegates at “The National Negro Convention of 1843” in Buffalo New York, Garnet called the Declaration of Independence “a glorious document. Sages admired it, and the patriotic of every nation reverenced the God-like sentiments which it contained.” Yet once in power, Garnet growled, the revolutionaries “added new links to our chains.”

Garnet despised the South’s “guilty soul thieves.” But he also disdained African-Americans’ “Patient sufferers.” He cried: “Behold your dearest rights crushed to the earth! See your sons murdered, and your wives, mothers and sisters doomed to prostitution. In the name of the merciful God, and by all that life is worth, let it no longer be a debatable question whether it is better to choose Liberty or death.”

Detailing slavery’s crimes prompted a religious decree. “To such degradation it is sinful in the extreme for you to make voluntary submission,” Garnet proclaimed. “Therefore, it is your solemn and imperative duty to use every means, both moral, intellectual, and physical that promises success.”

Garnet was exposing the American Revolution’s hypocrisy. It created the ideological infrastructure for outlawing slavery—“all men are created equal”—without executing it.

That lethal dawdle spawned what the activist W.E.B. Du Bois called African-Americans’ “two-ness”: too American to repudiate America, yet too scarred by it to adore it. Even Frederick Douglass, Garnet’s temperate rival, wondered in his anguished July Fifth oration of 1852: “What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July? I answer; a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim.”

Garnet’s radicalism came naturally—he was born into the unnatural hell of slavery in 1815. When he was nine, his parents used the permission they received to attend a funeral to escape.

Life up North was free but often uneasy. A teenaged Garnet fought off white neighbors determined to trash the integrated Noyes Academy he attended in New Hampshire with bullets he fashioned himself—resisting the rioters long enough so the students and teachers could escape. Returning to New York City after a second trip to Cuba in two years in 1829, Garnet discovered his family on the run and his sister recaptured. He hunted the slave-catchers, armed only with a knife, until friends spirited him to Long Island.

In 1834, he co-founded The Garrison Literary and Benevolent Association of New York, recruiting fifty blacks under twenty, only to be told to meet elsewhere or change the name. Honoring the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison was too radical for their public school venue. They rented elsewhere.

After his Presbyterian ordination, in 1839 Garnet became the pastor at the Liberty Street Presbyterian Church in Troy, New York. Two years later, he married an abolitionist writer Julia Williams—one of the students saved from the anti-Noyes Academy mob. They remained together until her death in 1870. Garnet said she helped write his fiery Resistance speech and others, explaining, “we twain are one flesh.”

Garnet’s 1843 address made him notorious. Even most black abolitionists found it too hard on the slaves and too violent. “However much you and all of us may desire it, there is not much hope of redemption without the shedding of blood,” he cried.” If you must bleed, let it all come at once—rather die freemen, than live to be slaves.” The convention voted down his speech—twice.

Anticipating Marcus Garvey, Garnet helped establish the African Civilization Society in the late 1850s. Garnet envisioned Africa as a “grand center of Negro nationality,” even attracting some American blacks to settle. His peers bristled, fearing racist cries to send blacks “back” to a continent most no longer knew.

During the Civil War, Garnet finally synched with the conventional black wisdom, as violence convulsed the land. Now based in New York, after the Emancipation Proclamation in January, 1863, Garnet blessed Abraham Lincoln as “an advancing and progressive man .... the man of our choice and hope.” After demanding that the Union mobilize black troops, Garnet became honorary chaplain to the 20th, 26th, and 31st regiments of United States Colored Troops.

Garnet’s prominence made him and his family targets during the draft riots of July, 1863—white neighbors saved them. Garnet then allied with whites to raise money for the victims while insisting that freed blacks needed jobs not handouts.

On February 12, 1865, Garnet sparkled as the first African-American to preach a sermon in Congress. Now ministering to the Fifteenth Street Presbyterian Church in Washington, tall and distinguished with fashionable muttonchops, wielding a booming voice and a commanding presence, Garnet celebrated the Thirteenth Amendment outlawing slavery. Rooting antislavery in Western thought back to the “lightnings of Sinai,” Garnet demanded that whites take responsibility for this national crime spree. Now, however, it was time to “emancipate, enfranchise, educate.” Using a delicious phrase capturing the challenge of evolving from slaves to citizens, Garnet said the legislation “marked the beginning of the end.”

Now prominent, if still controversial, Garnet served as president of Avery College in Pennsylvania. Organizing the Cuban Anti-Slavery Committee, he blasted abolitionists for declaring victory while slavery persisted in Cuba and Brazil. In 1881 Garnet became America’s minister to Liberia. He died there a year later. Mourners declared admiringly: “Having personally experienced the woes of the down-trodden of his race, he seemed all the better fitted to sympathize with the down-trodden and afflicted in every clime.…”

Garnet’s obscurity is unfortunate. His indictment of “The gross inconsistency of a people holding slaves, who had themselves ‘ferried o'er the wave’ for freedom's sake,” frames the African-Americans’ two-ness dilemma.

Pitting Garnet against Frederick Douglass as the first of the Great Black Rivalries frames this critical two-centuries-old crusaders’ conundrum. It’s between Booker T. Washington’s education-based moderation and W.E.B. Du Bois’ more politicized radicalism. It’s between Martin Luther King’s patriotic advocacy and Malcolm X’s militancy. It’s between Barack Obama’s mastery of the system and Ta-Nehisi Coates’ contempt for it.

Those dueling duos represent the classic schism between the reformer and the revolutionary, between the creative disrupter and the by-any-means-necessary rebel. Ultimately, of course, each has a different role in pushing democratic societies to live up to their best selves, individually and collectively.

FOR MORE

Joel Schor, Henry Highland Garnet: A Voice of Black Radicalism in the Nineteenth Century, 1977.

Manning Marable & Leith Mullings, Let Nobody Turn Us Around: An African-American Anthology, 2009.

Deborah Gray White, Mia Bay, Waldo E. Martin Jr, Freedom on My Mind: A History of African Americans, with Documents, 2016.