In 1883, Cornelius Vanderbilt II and his wife Alice posed for a photo before attending the fancy dress ball thrown by Vanderbilt’s brother, William Kissam Vanderbilt, and his wife Alva.

It was the event of the era, and the sepia-toned image shows Vanderbilt dressed as King Louis XVI complete with brocade overcoat, vest, and breeches, a pair of black stockings that end in pointed court shoes, and a white powdered wig. He holds a tricorn hat in hand, which appears to be trimmed in lush white fur.

His wife—his Marie Antoinette—is seated on a chair next to him. While not explicitly dressed as the infamous French queen, she is lavishly decked out in a masquerade gown made for her by one of the premiere couturiers at the time, Charles Worth.

The Electric Light dress gained historical renown for its cutting-edge technology. Hidden under the folds were batteries that lit up a lightbulb when Alice held it in her hand like the Statue of Liberty.

While the couple may have been dressed in costume, Vanderbilt’s choice of parroting the 18th-century French regent was apt. After all, they were living the life of utmost privilege and luxury, having just moved into their new Fifth Avenue mansion the previous year.

While their abode was brand new, it was hardly complete. By the time they were done gobbling up the surrounding brownstones and expanding their domain, they would create what was at the time the largest private home ever built in the U.S.

But this Fifth Avenue American palace, known as the Cornelius Vanderbilt II House, would survive for less than 50 years. By 1927, the crown jewel of an American royal family had been reclaimed by the the people… well, the people of high society, at least. The mansion was torn down to make way for the church of high fashion—Bergdorf Goodman—and many of the treasures the house held were scattered across the city for ordinary New Yorkers to enjoy.

The saga of one of America’s great homes all started in the late 19th century. The original Cornelius Vanderbilt, known as Commodore, was a poor Staten Island boy who had dreams of making it big.

With a $100 loan from his mom, he started a business to ferry people around the island. He would eventually turn this early success into one of the biggest transportation companies in American history. He became a railroad man and, at the time, being a train man meant amassing an unimaginable amount of wealth.

When he died in 1877, Commodore’s fortune totaled a whopping $100 million. He left the bulk of his estate to his eldest son William H. “Billy” Vanderbilt, as Commodore was of the old aristocratic mindset that your family fortune should remain intact and go to your firstborn. (His other children did not appreciate this notion and unsuccessfully sued for their share.)

Billy shared his portion with his children and, on his death in 1885, proved ol’ Commodore right when he split the bulk of the inheritance between his two oldest sons—Cornelius II and William Kissam. It was the beginning of the end of a dynasty. Starting with this generation, more money started to flow out of the coffers than came in.

But the survival of the family fortune was a concern for later generations. Upon Commodore’s death, his heirs took their newly acquired inheritance and began to build. The stretch of Fifth Avenue just below Central Park would come to be known as “Vanderbilt Row.”

It started with Billy building a giant brownstone double house between 51st and 52nd streets. Then, William K. built a French chateau a few blocks further north, and Cornelius II began a mansion of his own on 57th Street.

Ultimately, the Vanderbilts would build 10 grand homes on Fifth Avenue. In a stunning display of the changes that were occurring in American society at the time, as well as the vagaries of wealth, all of these would be gone by 1947.

In December 1878, The New York Times reported that the Vanderbilt of our concern—Cornelius II—had acquired two brownstones on the 57th to 58th Street block of Fifth Avenue for $225,000.

He had been talking about building a new mansion and it was correctly speculated that this was a sign that his next big project had begun.

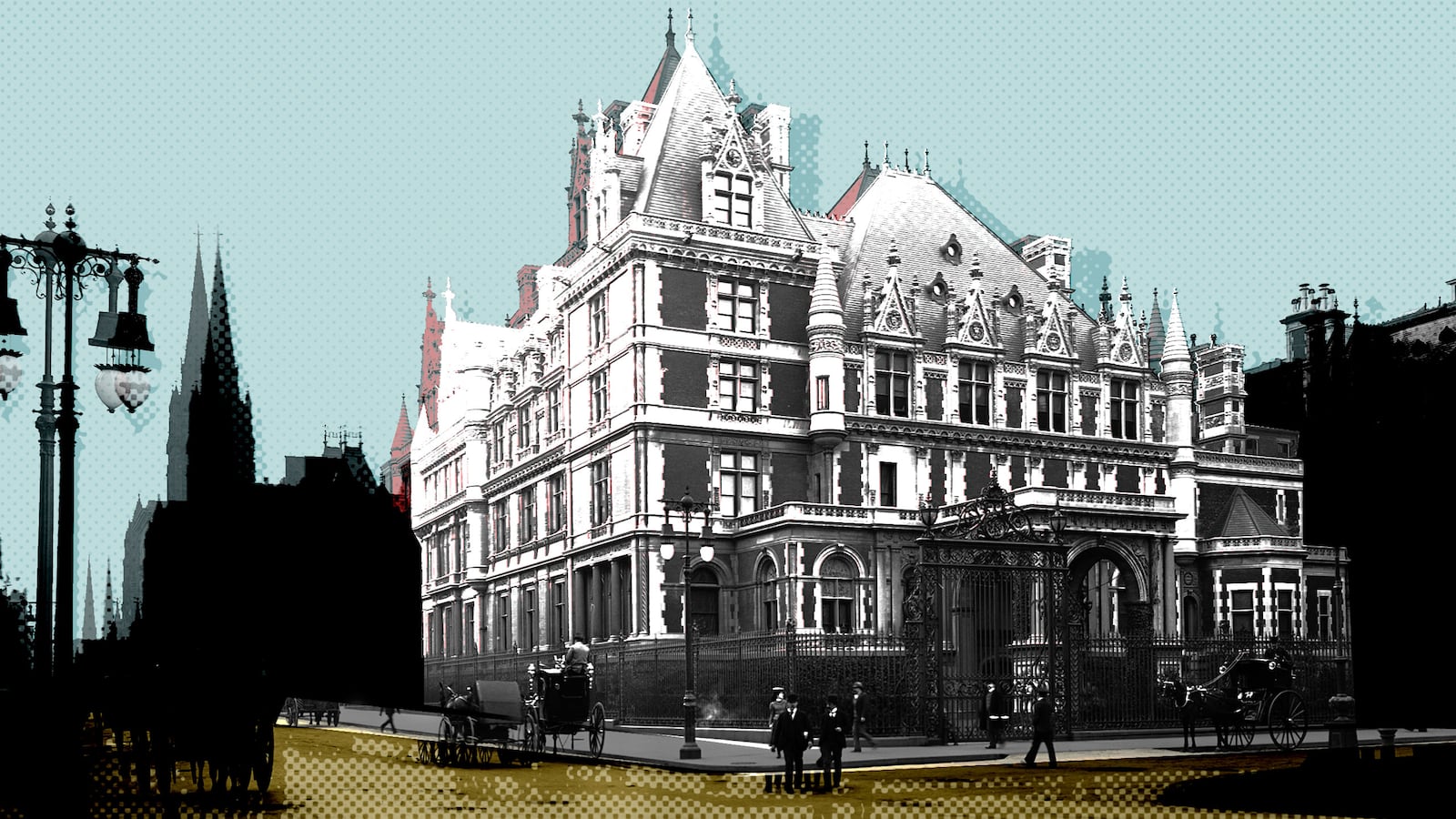

In 1882, the new Vanderbilt mansion was complete. It was fabulous, if modestly in line with the grandeur of the other mansions of the area. The outside was a distinctive red brick and limestone and it had already begun to have all the trappings of a French chateau (think crenellations and battlements and chimneys).

Over the next decade, the house would host more than its fair share of socialites and important players from around the world. Alice entertained lavishly in her new home. There were reports of the overflowing audience at a performance by a young piano prodigy who “showed his usual impulsive appreciation” of the treasures and finery that he saw on a tour of the house given by the young Vanderbilt children. He “would have wandered through the large apartments all day without tiring had he not been obliged to carry out his part of the programme.”

There was breathless reporting on how Mrs. Vanderbilt had decorated her quarters with soft mood lighting and a vast array of exotic flowers draped around the stairway, woven up columns, decorating paintings, and displayed in “extensive and beautiful” floral arrangements in order to entertain a French delegation for a breakfast.

And, of course, there were balls. For one soirée thrown for 250 guests in 1891, a tapestry was arranged to separate the vestibule where guests arrived from the main hallway. When each attendee was ready to make their entrance, the tapestry curtain would separate, and the honored guest would step through.

It was an impressive mansion where many visitors “oohed” and “ahed” over the decor and design. But when several different branches of your very rich family are all building their massive homes—or, rather, palaces—on the same street, you have to wonder, is yours impressive enough?

The answer to that question for our Vanderbilts was a resounding “no.”

Only seven years after they moved into their grand home, The New York Times was reporting that Vanderbilt had purchased two more brownstones on the same block so that he could expand the home that was “already a favorite for society people to visit.” He would eventually acquire and tear down five homes, and his mansion would end up stretching the entire city block.

According to the book Fortune’s Children written by a later Vanderbilt relative, it was “common belief that Alice Vanderbilt set out to dwarf her sister in law’s Fifth Avenue chateau, and dwarf it she did.”

By early 1893, the renovations were in full swing. The Vanderbilts were eager for the expansion to be completed as quickly as possible, so they arranged for more than 600 workers to labor day and night on the site under the light of electric lightbulbs when necessary. The job was scheduled to be completed in 18 months, although Vanderbilt allowed a two-month extension.

The talk of the town was all about the new mansion being built, but the Vanderbilts wanted to keep their plans a secret.

So they erected a giant wall along Fifth Avenue to shield the progress of the workers from the prying eyes of passersby. Even with this privacy guard, it was clear a massive project was underway. In the end, two major walls of the home were completely removed to make way for the addition and the still-new interiors were gutted.

By the end of the year, the house was complete and the reveal was jaw-dropping. The New York Times weighed in with the judgement that “it is a structure that would command admiration in any land of palaces and castles grand, for in its design, its noble proportions, and its artistic finish it is, in reality, a palace.”

Two giant wrought-iron gates opened on 58th Street to admit visitors to the circular carriage driveway that served as the formal entrance to the home, which contained 130 rooms and interior decor commissioned from some of the greatest sculptors and artists of the day.

Among just a few of the public rooms were a library, a small salon paying tribute to the style of Louis XVI, a grand salon decorated in Louis XV fashion, a giant grand hall, a watercolor room, an enormous ballroom, a Moorish smoking room, and a sizable dining room, not to be confused with the breakfast room.

While some could argue that renovating a home that wasn’t even a decade old was a bit much, the changes did come at an opportune time. In the early 1890s, modern bathrooms were just beginning to be installed in American homes. The Vanderbilts took eager advantage of these new developments in plumbing.

“In the new, palatial dwellings erected throughout the country by American millionaires, the bathroom has been brought to a point of perfection in which there seems nothing left to desire,” The New York Times reported in 1894, going on to say that many of these show “in every detail, elegance and exquisite taste.”

The Vanderbilt’s powder rooms were no different. Alice was reported to be the first person to use onyx in her bathroom. (Her sister-in-law and rival Alva was not to be outdone and was the first to deck hers out in Carrara marble.) The Vanderbilt children had all the luxuries the new bathrooms could provide and, according to the Times, no bathroom in the new home cost less than $3,000.

But the fanciest bathroom of all was enjoyed by the head of the household. Vanderbilt had not one, but four different types of tubs: “a porcelain tub, a needle and shower bath, douche bath, and sitz (hip) bath.”

Vanderbilt may have succeeded in his goal “to dominate the Plaza” with his new family home, but he wasn’t able to enjoy his success for very long. According to legend, six years after the family moved back in to their palace, Vanderbilt sat up in the middle of the night, told his wife “I think I’m dying,” and proceeded to do just that.

Alice stayed in the home for several more decades, but by the turn of the century, the Vanderbilts’ worst fears were starting to be realized. When the family decided to build their mansions along this stretch of road, the neighborhood was an upscale bastion of the fanciest family homes in the city.

They considered it gauche to mix private real estate with business, but, despite their vast riches, they couldn’t stop the onslaught of hotels and retail spaces making their way up Fifth Avenue.

The New York Evening Mail reported that, “By 1914, it was almost impossible to sell a private house for occupancy south of 59th.”

In 1926, Alice decided to sell the family home and its fate was sealed. Before the family moved out and the developers took possession, she decided to open the house to the public as a charity benefit. Visitors paid 50 cents to tour the American palace.

“The visitors seemed lost in wonderment at the glitter of the interior and most of all they seemed amazed at the hugeness of the rooms,” The New York Times reported on Jan. 10, 1926. “The wardrobes are the size of a modern hall bedroom and the bedrooms occupy as much space as a ballroom in a Park Avenue duplex apartment. A taxi could turn around in the bath rooms.”

With this last hurrah, the Vanderbilts gave up their crown jewel and it was torn to pieces. In its place would eventually rise Bergdorf Goodman, the famed high-fashion store that still enjoys the tony address today on the square it shares with the Plaza Hotel.

But not all was lost. Several pieces from the interior remain on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, including a stained glass lunette and a gorgeous red oak mantlepiece topped with a mosaic created by the sculptor Augustus Saint-Guadens.

And, today, visitors to the most democratic space in Manhattan—Central Park—who enter at 105th Street and Fifth Avenue pass through a stunning marvel of decorative design that was once a sign of unreachable privilege: a pair of wrought-iron gates that once welcomed visiting dignitaries and socialites to the largest private home in America.