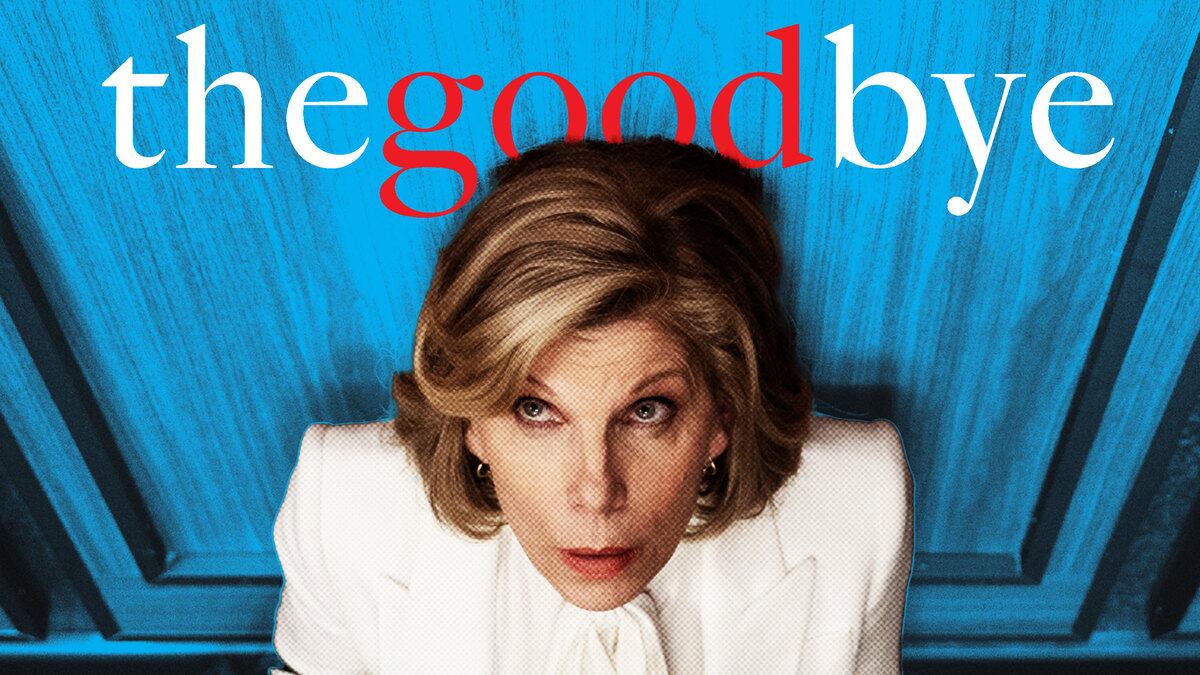

Goodbye, ‘The Good Fight’: The TV Show That Made Living in Trump’s America Tolerable

THE END OF EVERYTHING

After six flawless seasons, “The Good Fight” ended its run this week. The show helped us feel sane in a surreal world. What do we turn to now that it’s gone?

Trending Now