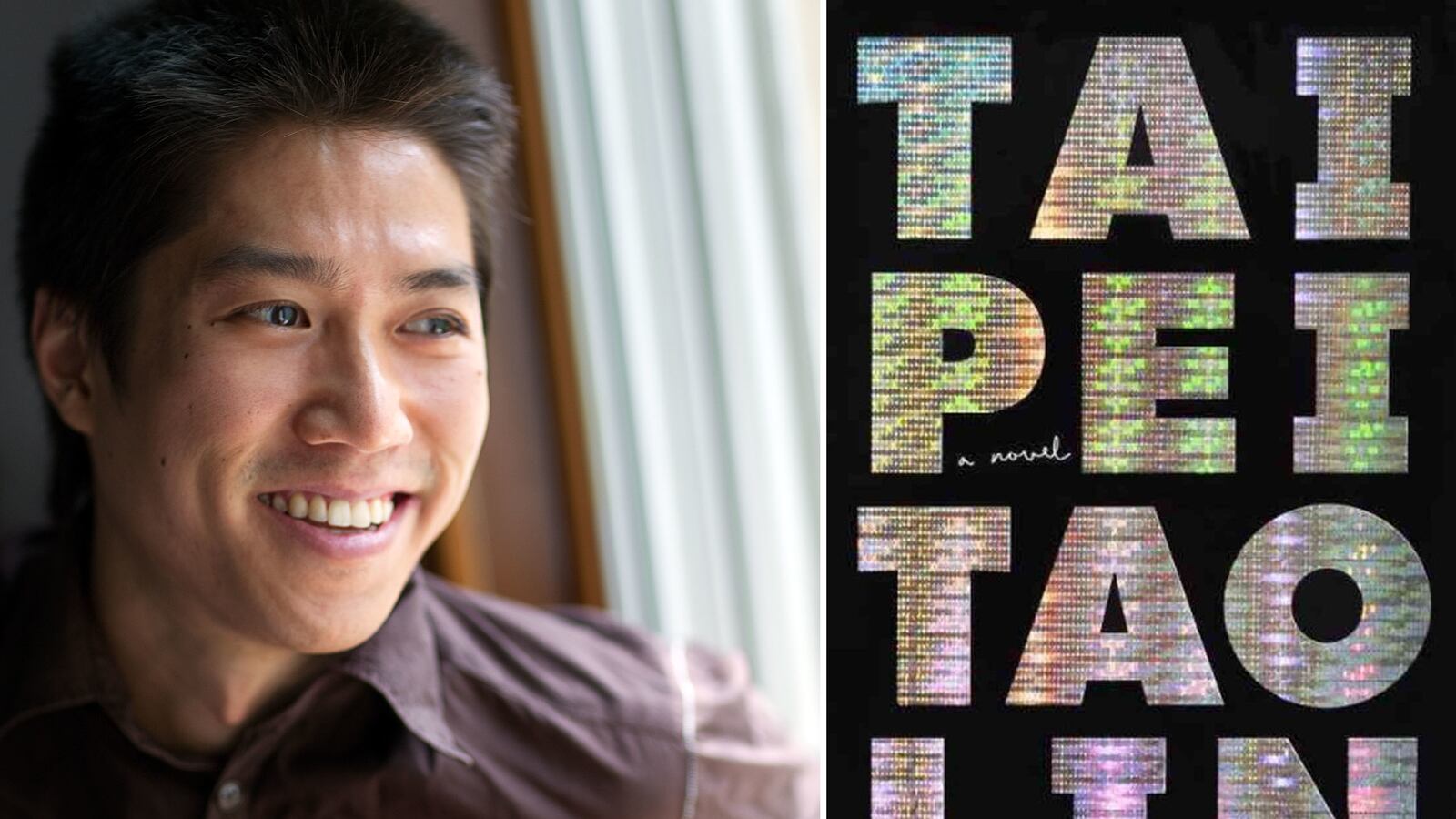

I’m always curious about whom Tao Lin is dating, as if he were a celebrity. To me he is one, in the sense that his life is an ongoing story I have followed since late 2010 through fragmented consumption of scraps of text, photographs, and video. I know all about Tao Lin in the same way that I know all about Kim Kardashian: he exists in a sort of miasma around the media channels I follow on my computer. I also subscribe to several Internet feeds produced by Tao Lin, in order to read his updates about his life, watch videos of his readings, look at his drawings, and enjoy his campaigns to make money or lose Facebook friends. He can be relied upon for consistent amusement. “Tao Lin,” the collected textual output of the Tao Lin I follow on the Web, was one of my favorite “books” before I had even read Shoplifting From American Apparel, Richard Yates, or any of Lin’s other works. For a while Lin was one of my favorite young writers, almost (but not quite) in spite of his novels.

I like his novels and his Twitter feed equally. They also complement one another. Since Lin uses the Internet as a repository of initial writing—drawing from both his public postings and his private communication in Gmail for his novels—part of what I enjoyed about his newest novel Taipei was the sensation not of reading but of rereading. Taipei is like a celebrity memoir: I’ve watched this movie already, and now I know that Tao Lin was high the whole time.

Taipei is a bildungsroman where the coming-of-age of the main character, a writer in his mid-20s named Paul, bridges two technological eras. The first era is not defined as the time without computers, the Internet, or iPhones, but rather is represented by the expectations, fears, and ideas about adulthood expressed by the character of Paul’s mother. Paul’s mother thinks that experience outside of the Internet makes a person more interesting, she believes that a mind on drugs is a compromised mind, and she thinks of relationships as two people in love who are nice to each other. Paul, in contrast, lives according to the maximum possibilities of the present: he makes little distinction between the parts of his life that are mediated through his computer and the parts he experiences physically. He also does not distinguish between a physical state of sobriety and one on drugs. His relationships are fragile, tenuous things where petty irritations and insecurities will, with time, always overwhelm the desire to love and be loved.

This destruction of another generation’s notions of physical and mental authenticity is further reinforced through consistent violation of the rules of standard written English. Prescriptivist grammarians will have a boisterous time reading Taipei. Nouns are adjectives, subjects disagree with objects, modifiers dangle, malapropisms abound. There are the many-claused thickets of adverbs and unlikely similes of writing done on Adderall. (My favorite of the similes: “Cleveland’s three tallest buildings, each with a different shape and style of architecture and lighting, were spaced oddly far apart, like siblings in their thirties, in a zany sitcom. After spending their lives ‘hating’ one another in a small town, they moved to different cities and were happy, but now have been coincidentally transferred by their employers to the same medium-size city. They were all named Frank.”) Lin’s medium is what writing teachers call “bad writing.” It tells, rather than shows. As he has in his previous novels, Lin repeatedly describes characters’ “facial expressions” (one of the more amusing parts of Richard Yates was its index, where “facial expression” had its own entry followed by “alert,” “amused,” “angry,” “bored,” etc.) Lin also continues to treat Gchat conversations as dialogue, reminding us that dialogue in a novel is not “spoken” either. For people who can’t let go of received ideas of what constitutes good writing, reading this novel will be a nightmare, but they will also miss the point: the language is part of Lin’s ongoing question of what is “speech” and what is “writing,” what is sobriety and what is intoxication, and what is digital and what is real. When I read a possibly erroneous phrase—say, “needless intimacy,” where I wondered whether Lin meant the dictionary definition of “needless” as unnecessary or avoidable, or if he meant “without need”—the ambiguity felt right. It was like the feeling of trying to decipher the meaning in a text message, or of staring at a person’s photo online and trying to gauge whether he is happier than I am. Lin’s writing makes me ask the same question: “Am I reading this the wrong way?”

Like Tao Lin, Paul is born in Virginia to parents who immigrated to America from Taiwan. Possibly like Tao Lin, Paul is the coddled favorite of a loving, overprotective mother. Paul grows up in a Florida suburb and becomes very shy in high school. He blames this problem on his mother: “In Paul’s sophomore or junior year he began to believe that the only solution to his anxiety, low self-esteem, view of himself as unattractive, etc. would be for his mother to begin disciplining him of her own volition, without his prompting, as an unpredictable—and, maybe, to counter the previous fourteen or fifteen years of ‘overprotectiveness,’ unfair—entity, convincingly and not unconditionally supportive.” To try to encourage these reprimands, Paul provokes fights with his mother, which “maybe contributed to Paul’s lungs collapsing spontaneously three times in his senior year,” as a result of which Paul can’t smoke marijuana for the rest of his life. He goes to college at New York University, begins his career as a writer, and at the start of the novel is 26 years old and awaiting publication of his next novel in New York City, where he goes to lots of parties.

In the first chapter, Paul breaks up with his girlfriend and travels to Taiwan. After 30 years in the United States, his parents have moved to a 14th-floor apartment in Taipei. During his visit, Paul’s mother suggests he also move there to teach English: “She mentioned Ernest Hemingway more than once while saying Paul would benefit, as a writer, from the interesting experience.” Paul disagrees, preferring America, “where he could speak the language and maintain friendships and ‘do things,’ he said in Mandarin, visualizing himself on his back, on his yoga mat, with his MacBook on the inclined surface of his thighs, formed by bending his knees, looking at the internet.” Paul does not think an extra-digital self who attends bullfights or deserts the army has anything better to write about than one who spends his time, as Paul later does, clicking through approximately 1,500 Facebook photos to see if a girl he likes has untagged herself.

Back in America, Paul begins what he thinks of as a five-month “interim period,” leading up to his fall book tour. During this time, he plans on “being productive in a low-level manner, finding to-do lists and unfinished projects in his Gmail account and further organizing, working on, or deleting them, for example.” Instead, he goes to parties and pursues relationships with women. The interim period takes a turn when, “In early June, after four more parties, two at which he similarly slept on sofas after walking mutely through rooms without looking at anyone, Paul began attending fewer social gatherings and ingesting more drugs.”

The descriptions of drug use are endless, but it’s fine: the point is that even interactions in the physical world, IRL and AFK are only so much coding. When Paul’s mother, who also follows his Internet updates, begins sending worried emails about his increasing drug use, Paul responds “that there was no such thing as a ‘drug problem’ or even ‘drugs’—unless anything anyone ever did or thought or felt was considered both a drug and a problem.” Paul starts a new relationship, with Erin, that’s conducted as passively as possible, through mutually high levels of Internet activity. Paul also begins his book tour, planning a schedule with what drugs he will ingest “before twenty-two of his twenty-five events.” He travels the country. He allows himself to “become ‘obsessed ‘ to some degree” with Erin. She visits him in New York, where they spend Paul’s last $1,200 on a package vacation to Las Vegas. Then they get married.

The novel descends into familiar territory—the confines of a relationship—that Lin covered in Richard Yates, which was a harrowing account of a horrible relationship. It’s also familiar because Tao Lin married a writer named Megan Boyle in Las Vegas, and I read all their posts about it. Erin and Paul spend so much time together they become estranged. They go to Taiwan and do drugs there. Paul’s mother asks Paul to be nicer to Erin. They go back to New York. They take Xanax. They snort heroin. At the end of the book, they’re on shrooms and still together. Tao Lin and Megan Boyle have divorced.

Taipei is exactly the kind of book I hoped Tao Lin would one day write. He is one of the few fiction writers around who engages with contemporary life, rather than treating his writing online as existing in opposition to or apart from the hallowed analog space of the novel. He’s consistently good for a few laughs and writes in a singular style already much imitated by his many sycophants on the Internet. Some people like Tao Lin for solely these reasons, or treat him as a sort of novelty or joke. But Lin can also produce the feelings of existential wonder that all good novelists provoke. His writing reveals the hyperbole in conversational language that we use, it seems, to make up for living lives where equanimity and well-adjustment are the most valued attributes, where human emotions are pathologized into illness: we do not fall in love, we become “obsessed”; we do not dislike, we “hate”. We manipulate ourselves chemically to avoid acting “crazy.”

Early on in Taipei, Paul imagines moving to Taipei alone “at an age like 51, when maybe he’d have cycled through enough friendships and relationships to not want more.” Because he does not speak Mandarin very well, he would be autonomous and “secretly unfriendable.” Gradually, in this environment, “a second itinerant consciousness” will come to take over: “The antlered, splashing, water-treading land animal of his first consciousness would sink to some lower region, in the lake of himself, where he would sometimes descend in sleep and experience its disintegrating particles—and furred pieces, brushing past—in dreams, as it disappeared into the pattern of the nearest functioning system.”

And isn’t total absorption into a functioning system a sort of dream for many people? There is still a binary here, not between “the digital” and “the real” but between the ungainly, the inconvenient, and the primitively emotional, and the perfected self without need of others, constructed through new channels of image and text. Paul would be freed, in Taipei, from language. But he returns to America, “where it seemed like the seasons, connecting in right angles for some misguided reason, had formed a square, sarcastically framing nothing.” He imagines the hollowed frame of life in America as a doorknocker, and a child with the doorknocker in his hand, knocking, “unaware when he will abruptly, idly stop.”