Adam and Frankie Mitchell, real Brooklyn dead-end kids, were raised on East 38th Street, last house on the left, up against the freight train tracks. It’s a great place to raise two teenage boys in the ’70s, like Altamont was a great place for a free concert.

What could these poor boys do? Not try to be street fighting men, and they sure as shit weren’t singing in a rock-n-roll band. When you live next to train tracks, there’s only one fate for you, you are going to cross the tracks. In the ’80s, in south Brooklyn, that means getting into trains and graffiti. This is the era that the area became synonymous with the phrase “racial incident,” so white kids running the tracks and tagging up VEN (Adam) and BONES (Frankie) was a really, really bad idea.

Frankie (older by four years and 10 months) and Adam were already on the wrong side of the tracks just by living in Flatbush. Over there they beat down people quick as making a right turn on red. Flatbush is full of working-class Irish and Italian, real rock-n-roll-types, and here comes Mr. and Mrs. Mitchell, some disco-roller-skating-types. He’s got gold chains, he’s driving a Barracuda, she’s pretty, and they both are wearing the latest designer threads from 8th Street. That’s already five strikes against them on a block where nobody’s got none of that. So Adam and Frankie got struck a lot. No big deal, they struck back, it was just a tax on a good time, and like the extra quarter tax Frankie would pay when he bought a record, it was almost painless.

By the time he was 18 years old Frankie already had thousands of records, the first of which he bought at the age of 11, the 45 of “Ease on Down the Road.” At 12 years old, May 14, 1978, he eased on down to Roller Palace, where he learned to skate, date, program music, and DJ. The last of which he parlayed into making mixtapes, which, once sold, bought more records. Making mixtapes eventually led Frankie to Kings Highway and Caesar’s Bay Bazaar, where he sold mixtapes out of Mo’s Car Stereo Booth. Mo did all right with car stereos, everybody in south Brooklyn in the ’80s had to replace at least one. But car stereos was just the icing, Frankie’s mixtapes made the cake. There was a lot of cake to make, according to Frankie. “WKTU stopped playing disco in 1982, and Hot 103 started playing dance music on August 15th, 1986. I don’t know how I remember these dates.” Oh, Frankie has an amazing memory for dates. Until that date in 1986 Frankie had a four-year run on the tape decks of Brooklyn. He became a well-known purveyor of breaks, freestyle, and hip-hop mixtapes.

Adam’s getting off the block, too, riding trains throughout the city with a camera and taking pictures. For decades rail fans have ridden trains and taken photos. Most of the older rail fans hated graffiti for sullying up their beloved Red Birds, but Adam’s generation accepted it as part of the landscape. Frankie was up on trains as BONES, and naturally after about a month of only taking photos, Adam crossed over into writing VEN, easy as hopping the turnstile. When BONES was active in the early ’80s, he wrote a lot of graffiti on the train lines in Brooklyn, just like hundreds of other kids. When Adam started writing the trains were being cleaned and a lot of kids were discouraged enough to stop painting trains. VEN was only encouraged and took full advantage of the opportunity to paint whole cars as much as possible. By the time the last graffiti-covered train was pulled out of service (Frankie: “August 12th, 1989”) there were maybe a dozen other writers on VEN’s level. He kept on painting like it was 1979, and in doing so VEN inspired and infuriated thousands. So VEN won accolades and vandal squad surveillance. Status brings static, always.

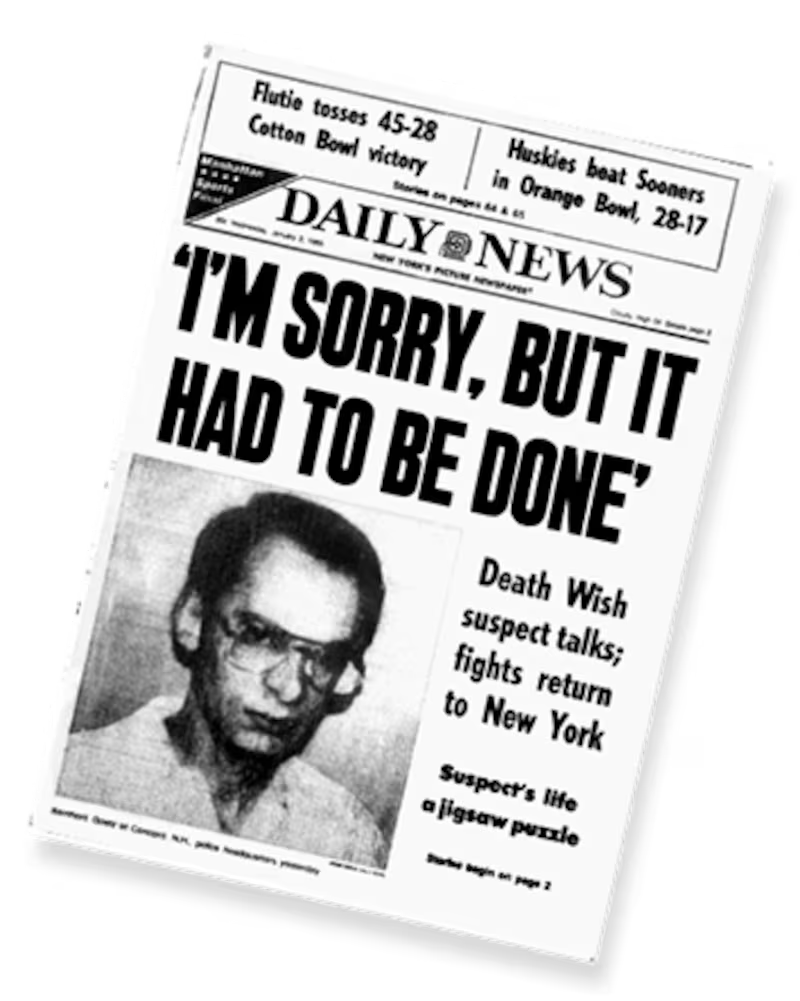

At the same time Adam and Frankie are living the hip-hop dream, they are also living the New York nightmare. Willie Turks, a black transit worker beaten to death by whites in Coney Island. Michael Griffiths, a black man chased onto the highway by whites in Howard Beach. Adam and Frankie can tell you where they were on December 22, 1984, when Bernie Goetz shot four black teenagers on the 2 train near Franklin Street.

The wave of anger and terror crashed right into their house a month later when a black man murdered Adam and Frankie’s dad, who was moonlighting as a taxi driver. So many cabbies were getting murdered then in New York City that Miles Mitchell’s death didn’t rate a mention in the papers. So many random murders that it was just a fact of life that if you were in the wrong place at the wrong time you were getting killed. The wrong place was New York City, and the wrong time was any time in the ’80s.

Adam, still a minor, was spared going to the trial but Frankie (“I turned 18 on October 17, 1984”) went every day. It turned out to not be a black/white crime, it was so complicated and convoluted, it was more gray (for the murk)/green (for the work). The defendant and his two codefendants (turned witnesses for the prosecution) all had conflicting accounts, none of which made dollars or sense. Frankie sat on the bench, dumbfounded at the stupidity, and thought about the last time he saw his dad: He punched Frankie in the mouth for breaking curfew. Worse than that regret for Frankie was that he was denied the rite of passage granted to working sons of working-class Brooklyn fathers: “The next time he would’ve passed the joint to me.”

Frankie and Adam have a good brotherly rapport with each other. They argue constantly, but never fight, and they maintain the baseline love for each other that they were born with. Their father’s death, while horrible on its face, gave Adam the freedom to go and become a graffiti king, and Frankie the determination to get into the music business. Their father’s death was terrible but it was on the record, and the song kept playing. So they stayed in the groove, because what are you gonna do? Or as VEN’s boy REAS says they say in Brooklyn, “Whamdoo?”

On May 3, in 1987, Frankie got a job at Apexton, a record pressing and distribution facility in Queens. He was literally moving units, boxes of them in the warehouse from the stamper to the shipping department. One day he walked off the floor up the steps to the boss’s office, uninvited. He was drawn by the sound of what turned out to be the music of the eventually legendary house music producer Todd Terry. The boss was listening to a test pressing of Terry’s debut single (as Masters At Work) “Alright Alright.” It sounds like Kraftwerk and Bambaataa and DMC got on a conference call.

The Apexton boss yelled for Frankie to come into the office. He looks at Frankie in the doorway and yells, “What the fuck are you doing up here?!” Frankie answers by asking, “What is that?” Boss lowers the volume. “You like this? We were wondering if we should press it.” Frankie says fuck yes. The record gets pressed and sells 8,000 units in a month. If a major label releases a song that sells 500,000 records it’s a gold record, and the profits are split a hundred ways. For an independent record label that presses its own records? That doesn’t spend a nickel on promotion, distribution, A&R, radio, or royalties? That’s black gold.

The boss, being a boss, promotes the stockboy and Frankie starts moving units figuratively as an A&R and recording artist for a number of “Label in Name Only” labels, which operated under the roof of the Apexton pressing plant. Apexton was an admirable all-American operation run by an all-American Albanian family. It was a great/shady/uncertain business to be associated with. But, as much as Frankie was learning about making records, he had the same feeling as he had selling tapes at Caesar’s Bay—always being owed, never owning.

The records Frankie Bones made at Apexton find a receptive audience in England, and he gets invited to spin at a rave called Energy in the summer of 1989. Raves, illegal dance parties, were just starting to flourish in England, and Frankie was right on the curve. He arrived expecting a crowd of 300 and was stunned to be performing for 25,000. He couldn’t even imagine an event like that in New York City, which was still marinating in its own fury. The night Bones DJ’d in England, August 29, 1989, a night that he saw an idyllic possible future—was only a couple nights after Yusef Hawkins was chased into traffic and murdered in Bensonhurst. How the fuck could anybody unite a crowd together in New York without any bloodshed?

Ecstasy, for starters. Frankie brought home some pills and passed them out to the crew. “This is what’s propelling the scene in the UK.” Adam had his screw face on until the E kicked in. “Suddenly I was inside the music.” It was as if the New World was on the horizon and Frankie and Adam were sailing on the Niña.

Next port of call was Los Angeles, where Bones’s rep in England had reached the ears of rave promoters. They were sure they had the wrong DJ Bones when they heard his Brooklyn accent, but after flexing his credentials for the length of the ride to the venue, Bones took his place at the tables in front of 5,000 people. Adam was along for the ride and realizing not only was his brother a star, he was doing something the other DJs weren’t: Some of the DJs were just cueing up records, but he was actually mixing. Like graffiti, anybody can do it, but only a few do it. Before long, Adam had started to learn to do it, too. Frankie was well-versed in keeping a party going for hours, building and sustaining a vibe and keeping the crowd moving. As a DJ, he’s got a classic club approach to the turntables. Where he goes, and again, Adam (now Adam X) follows and goes beyond, is to the faster, industrial, electronic Man Machine Music built by Kraftwerk that rode the Autobahn of Germany and found its way to the highways of Detroit and the subways of Brooklyn and eventually everywhere.

The techno that Frankie spins has echoes from all the music he spun growing up, just faster. The first thing that comes to mind when I think of Techno is the beat that goes “doosh doosh doosh.” There’s some of that in what Frankie spins, but there’s a lot personality and a party vibe to what he does. In techno, every sound is percussive, an idea that James Brown invented in the ’60s but sped up to the point where most vocals and melodies are jettisoned to reduce drag. It’s like the soul train transformed into the Bullet train. The records only hint at what happens when the music is played live at a rave with a proper sound system. There’s physicality to the music that’s a visceral experience. The beat vibrates your body, you can’t not participate in the music. Even if you’re standing by the wall, it’s going to move you anyway. That’s the point of a rave, everybody pays their money to be moved by the beat. Some here are really getting their money’s worth by dancing in front of the six-foot-tall rack of subwoofers, which is loud two blocks away, never mind two inches.

Adam X reduces the music to industrial rhythms and raw bass being delivered in a hundred frequencies. One of Adam X’s moves is to gate the bass—twisting a nob to close down the bass, then twisting the nob back to open the bass until my solar plexus is vibrating. When Adam X takes the bass away you can see the crowd deflate, and when he gives it back you can feel the crowd surge off the dance floor.

Bones closed out his LA trip with a meeting with a promoter who said, “Some guys are coming to New York to check you out.” It was said with the tone of a vague record-industry promise, one-third light and two-thirds shade.

Bones received the “some guys” at his home in Brooklyn, and after a couple hours of small talk, nods were exchanged between the visitors. One guy went out to the car and returned with a suitcase packed with 2,000 Ecstasy tablets. In Adam’s opinion, “It was the best batch of Ecstasy ever in the rave scene in NYC.” Bones was told he was now in business and the money owed was his responsibility. Everybody shook hands and the guys went back into the night. Bones never even touched the case; he made a call and within minutes was relieved of the burden. That call kept him alive and free, but he was going to pay a tax. No biggie, charge it to the game.

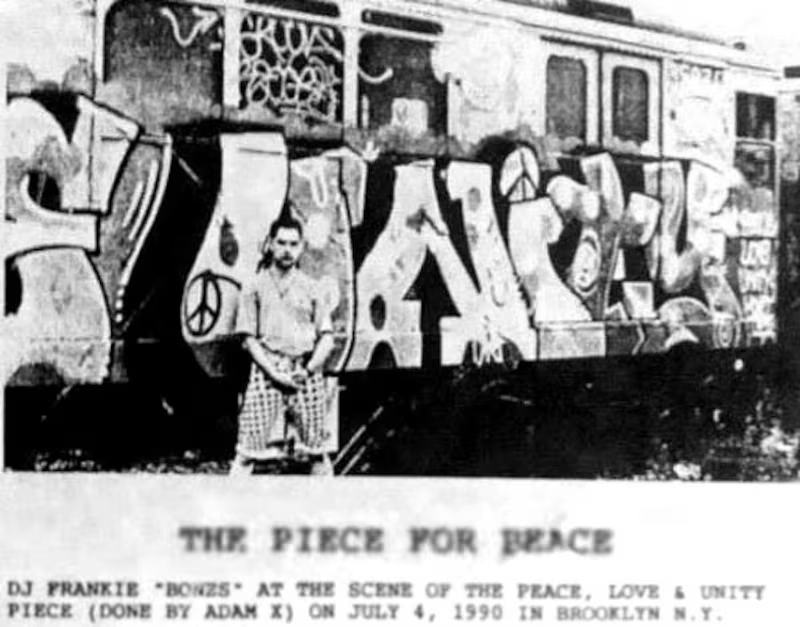

Avoiding the drug-dealing pitfall, Frankie turned his attention to stopping the violence that was trying to rob him again and again of everything he loved. Ecstasy definitely cooled things for a time, but Frankie wasn’t fooled. Violence was leaning on the wall waiting to fuck up the party. In the middle of a club date one night, a fight flared up and Frankie took charge, jumping up on the table and yelling, “You better start showing some peace, love, and unity or I’ll break your faces.” He had been to the tabletop, and came back with a dream: PLUR: Peace Love Unity Respect. “Correction, it was PLUM, the M is for Movement.” OK, noted, but it morphs into PLUR, and PLUR it is. In spite of Frankie’s parental misgiving, PLUR is a good dream. But if Frankie was gonna sell that, he needed a billboard. No problem, VEN’s got an outline and a bag of paint, so they go back to the tracks, this time a scrap yard in Brooklyn, and July 4, 1990, VEN paints a train end-to-end PEACE LOVE UNITY. It’s daytime when he does this in full view of anybody passing by on 36th Street. Frankie stands on the street holding a clipboard. When the cops roll up, Frankie sells them the dream, and it’s the best thing they heard all week. Cops roll away, VEN finishes the train and PLUR has its billboard.

PEACE, LOVE, UNITY was a bit of programming they knew had to be in place before they could think about throwing a rave in New York. The first place they test-marketed the program was at their Groove Records store in Bensonhurst. Frankie opened the store in April 1990, at 64 Avenue U, steps away from the Mighty Marlborough Houses, home of SAGO and BOE of maybe the greatest graffiti crew RTWOW, and also HOW, LITTLE, and representatives of every street expression imaginable. It’s also steps away from the Guido mecca of L&B Spumoni Gardens. So, you can’t cut the racial tension with a knife here, you’re gonna need a Sawzall. Regardless of the tension, the store found a receptive crowd quick. Bath Beach Mafia kids, Black DJs from the projects, Spanish Freestyle kids, Italian cugines who never left the block, the Playboy Guidos that went clubbing all over the city, and club kids who would have been killed by the rest in any other context—all found a home at Groove. Once the congregation was in the store, it’s a perfect place to preach PLUR, even if practice was nearly impossible. Still, Frankie and Adam made it work; the store was the nexus for a couple of communities that made it their business to mind their own business.

With the success of the store Frankie and Adam were ready to put PLUR to the test with an illegal rave far from police or paramedic help. The potential for greatness and horror were equal, and these guys had had enough horror for one lifetime. In spite of all the danger, of every sign warning them NO, they went back to the abandoned tracks, in Brooklyn, with turntables, four crates of records, several speakers, and a few hundred feet of extension cord, loaded up a train track work cart, and pushed it a couple miles down some slow freight tracks, first behind a junkyard in Canarsie, and later a few miles farther down the tracks to an abandoned masonry yard. At the latter, their last illegal underground rave, cliché it isn’t so, plugged into a street lamp. Two thousand people came through and danced until dawn, when a photo sensor on the lamppost cut off the light and, consequently, the music. With Storm Rave, as they called it, Bones and Adam X closed down a fucked-up decade in New York. By the time the sun came up they had rolled up the gate on the much much better ’90s.

Storm Rave was the first rave in New York City, but it was also the continuation of a long history of dance music in the city, especially for these guys, who’d grown up in the light of Brooklyn’s Roller Palace. Music meant enough to the family that Miles Mitchell has a roller skate engraved on his headstone. This was Disco Destiny Fulfillment, so when trouble came, Frankie and Adam knew where they had to go and they went there together.

Within a year the rave business became a record industry success story, and with success came record industry levels of gangster. Any night that Storm Rave was on meant death for competing raves, so one kid who’s promoting a competing rave—a kid who got his start in the scene thanks to Frankie—stirs the pot with the mob kids in Bath Beach and they go bat down Frankie on his step to the tune of 300 stitches, four days before Frankie’s next Storm Rave. It didn’t stop Frankie. Four days later he was at the wheels, head wrapped like Erykah Badu.

Then the asshole takes it to another level. Two Dutch DJs from Rotterdam Records come to town to spin at Limelight, and arrived at the club carrying a white-label record that boasted vocal samples chanting, “Rotterdam is full of shit.” They have a meeting with the asshole, who’s still promoting, and still trying to shut down Storm Rave. The DJs are looking to hospitalize somebody, and the asshole blames Adam and Frankie for making the record to stir shit up. So Adam catches a lot of shit when the DJs corner him. Adam takes a quick look at the run-off groove of the record, and sees that the mastering engineer was Don Grossinger, which tells Adam the record came from Europadisk on Varick Street in Manhattan. Adam gets one of the DJs to call Europadisk. In thick Dutch-accented-English, the DJ represents himself as being from Sony Music, Holland. He goes on to say that the record contains unauthorized samples and demands to know the address of the producer. It turns out to be the asshole promoter. Adam gets invited to the watch the DJs perform the next night. As a bonus he gets to watch the shook promoter skip like a record.

Frankie and Adam became Bones and Ven and then Frankie Bones and Adam X, the names changed but the men STAY the same. They are strivers, going to the known limits and pushing beyond. It takes a lot of heart to leave your dead-end block, then go all over the world and see what real possibilities look like. It takes even more heart to bring those possibilities back to the neighborhood and kick-start an evolution. They could’ve moved to Manhattan and started with a camera-ready crowd built to play nice with each other. Instead they went home to a borough more thorough and made it happen. A heroic move that ensured PLUR for all time. They had such a good thing going uniting the scene, so naturally it had to come to an end. They pushed their luck when they held a rave in a parking garage in Manhattan’s meatpacking district, around the corner from the asshole promoter’s rathole at the Limelight. This Storm Rave brought trouble from every conceivable level, but true-to-form Adam and Frankie had an answer for every threat.

And they almost brought it off. At the height of the party, they had the off-duty cops they’d hired calming angry on-duty cops. Nearby a van full of mobsters intent on shutting down the party got outranked by the mobsters Adam and Frankie partnered with. But these amazing efforts only stalled the inevitable shutdown by the cabaret cops Dinkins put in place to keep clubs safe after the Happyland fire that killed 87 people the year before.

Time wouldn’t be up for the rave scene until well into Giuliani Time. But already in 1992 Storm Rave had gotten too big for Bones and Adam X. They quit while it was still on the upswing rather than watch it fall down the other side. Adam and Frankie played the last song of the night and went back to Groove Records, where they sold records and doled PLUR for the rest of the pretty good century and beyond.

Adam and Frankie were too practical for all the excesses that wiped out the club kids, and they were too underground to go the route of the club DJs who crossed over to pop music. They still make music, they still DJ around the world, and they visit Mom back in Brooklyn on the regular. There’s longevity in being sensible, a theory proven May 16, 2015, when Red Bull Music Academy put on a Storm Rave at a Brooklyn Warehouse deep in Bushwick on an appropriately drenched Saturday night.

After a 23-year hiatus, not much changed—of course, backed by the energy drink, they had a state of the art sound system, lights and dance floor (!) installed, but the crowd was still there. A thousand people traveled to the end of Bushwick and submitted themselves to the beat. I stood behind the speakers where the sound wasn’t crushing and thus was by myself watching the huge crowd begging for ADAM X to beat them with the bass. Adam whipped them for 90 minutes, and when he left the tables for his brother, the crowd started chanting “BONES BONES BONES...” For a couple guys that are working in an underground music few people even understand, it was an amazing affirmation of their achievement. They’ve managed to come so far and they are still real to the bone(s). In the end they can only be who they’ve always been, Brooklyn’s own. Whamdoo!