Newsweek was just coming into its own when the ’60s began to unfold, along with the movements that would change America, all for a new generation of journalists to cover. The Washington Post’s brilliant and charismatically flamboyant publisher, Phil Graham, had been persuaded by his good friend Ben Bradlee to buy the magazine, and that’s how Newsweek became part of the storied Washington Post family. It was 1962, and Bradlee, the magazine’s Washington bureau chief, would soon jump to the Post. Both men were close to the new president, socializing with the first family, hearing but never betraying JFK’s confidences, and being part of the inner circle elevated the Post and Newsweek too in status-conscious Washington.

It was all so glamorous, this dynamic publisher at the helm of two solid media properties at a time when politics and journalism were just beginning to meld in a way that captured the public’s imagination. But Phil Graham had his demons, his fantastic energy and mercurial emotions driven by what would later be diagnosed as bipolar disorder, and on an August day in 1963, he put a gun to his head and committed suicide. He was 48 years old. His wife, Katharine, heard the gunshot and went to him.

He had humiliated her, openly having an affair with a much younger Newsweek researcher, but Katharine Graham knew she was dealing with mental illness, and she was made of strong stuff. Left a widow with four children, the youngest just 10 years old, she stepped up to the task before her, shouldering an emerging media empire despite her many insecurities about whether she was up to taking over from the husband who in life had so overshadowed her.

I was shocked by the announcement Monday that Jeff Bezos of Amazon fame is buying the Post and that the Graham family had somehow acquiesced to selling the newspaper that has been so central to life in Washington for so long. Katharine Graham was not an absentee owner; every reporter at Newsweek knew that “Kay” let the editors know what stories she liked to see and how she would run interference when we stepped on the toes of someone in her social circle. She regularly lunched with Nancy Reagan, whom she considered a friend, and we would hear about how “Ronnie” felt about this or that. But when push came to shove, notably during Watergate, there was never any question about Katharine Graham’s resolve.

I came to Washington after covering Jimmy Carter’s presidential campaign, and to welcome me, she invited me to one of her salon dinners. I didn’t know anybody, and the elegant woman I stood next to during the reception warned me she wasn’t anybody—she was Drew Pearson’s widow. I had read and admired his columns from afar, and I told her that to me she was somebody. I was starstruck. I sat next to Bob Woodward at dinner. Still in the early stages of fame, he seemed somewhat apologetic for dining out in such grand fashion. “We should be knocking on doors, doing our jobs,” he said.

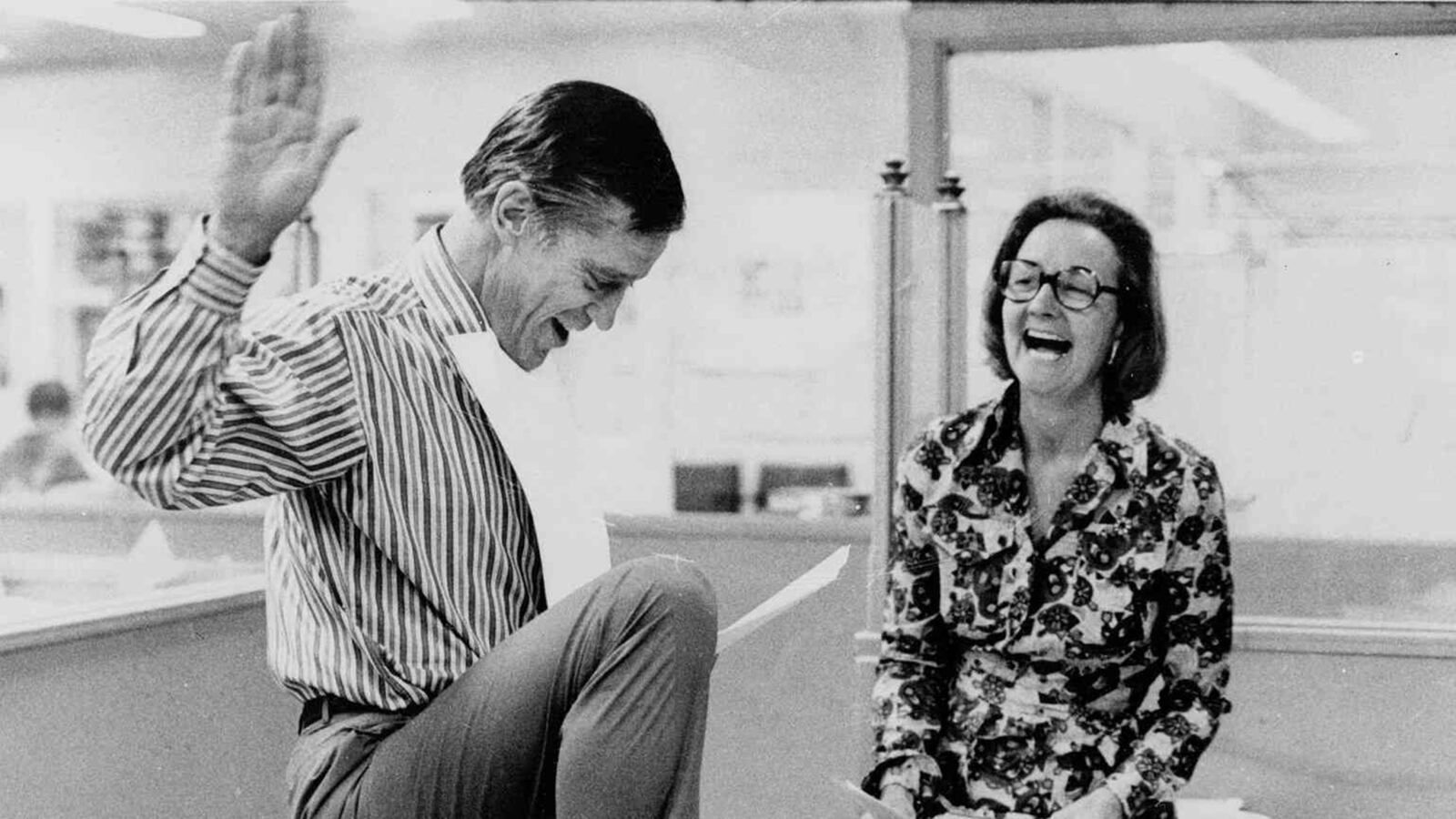

When Katharine Graham handed the baton to her son in 1979, it seemed the most natural and right thing to do. Donald Graham had been groomed for decades to become publisher. He had worked in all areas of the newspaper, and at Newsweek he had been a writer in the national affairs section. He knew every job intimately, and as publisher he made a practice of inviting employees to informal Friday lunch buffets at the Post just to get to know them better. He knew the pressmen by name. He was also a fixture around town, a contributor to animal causes, to the Capital Area Food Bank, a soft touch when it came to philanthropy.

He didn’t face a challenge as great as his mother did in confronting a ruthless and desperate White House, but his journalistic spine in the defense of his reporters was never in question. Some grumbled about the newspaper’s departure from the liberal orthodoxy that had governed its editorial pages in the aftermath of Watergate, but that was more a reflection of the changing politics than any strong ideological shift by Graham. Conservatism was no longer the outlier; it was and still is at the core of our politics.

If the son can be faulted, it would be for lack of vision. By the time he turned the family-owned business over to his niece, Katharine Weymouth, it had become too tightly shackled, without enough diversification, and too dependent on a single acquisition, Kaplan, and its testing franchise. When newspaper ad revenues began to tank and Kaplan was fat and happy, Graham said, only half-joking, that soon The Washington Post would be an education and media company, not the other way around. The tail would be wagging the dog.

Seven months after Weymouth took over in early 2008, the economy went into a free fall. Her appointment, contentious to begin with, soured as she presided over bruising cutbacks and layoffs of staffers, along with a ham-handed attempt to raise revenue by holding salon dinners at her home, crossing the sacred line between the editorial and business sides of the Post. Wounded by the negative publicity, she pulled back and never became the prominent figure her grandmother and father before her were in the community. I heard her speak in March at the American News Women’s Club, and she came across much more appealing than her public image, which let’s face it, isn’t that high a bar. Weymouth is a hard-nosed lawyer, more focused on the bottom line than the public trust, and the bottom line for the Post is unforgiving. She couldn’t make the numbers work, and rather than ride the roller coaster all the way to the bottom, she made the decision that now was the time to bail. It’s a sad day for what we now call old journalism. Let’s hope the new digital era finds a way to honor the best of what went before.