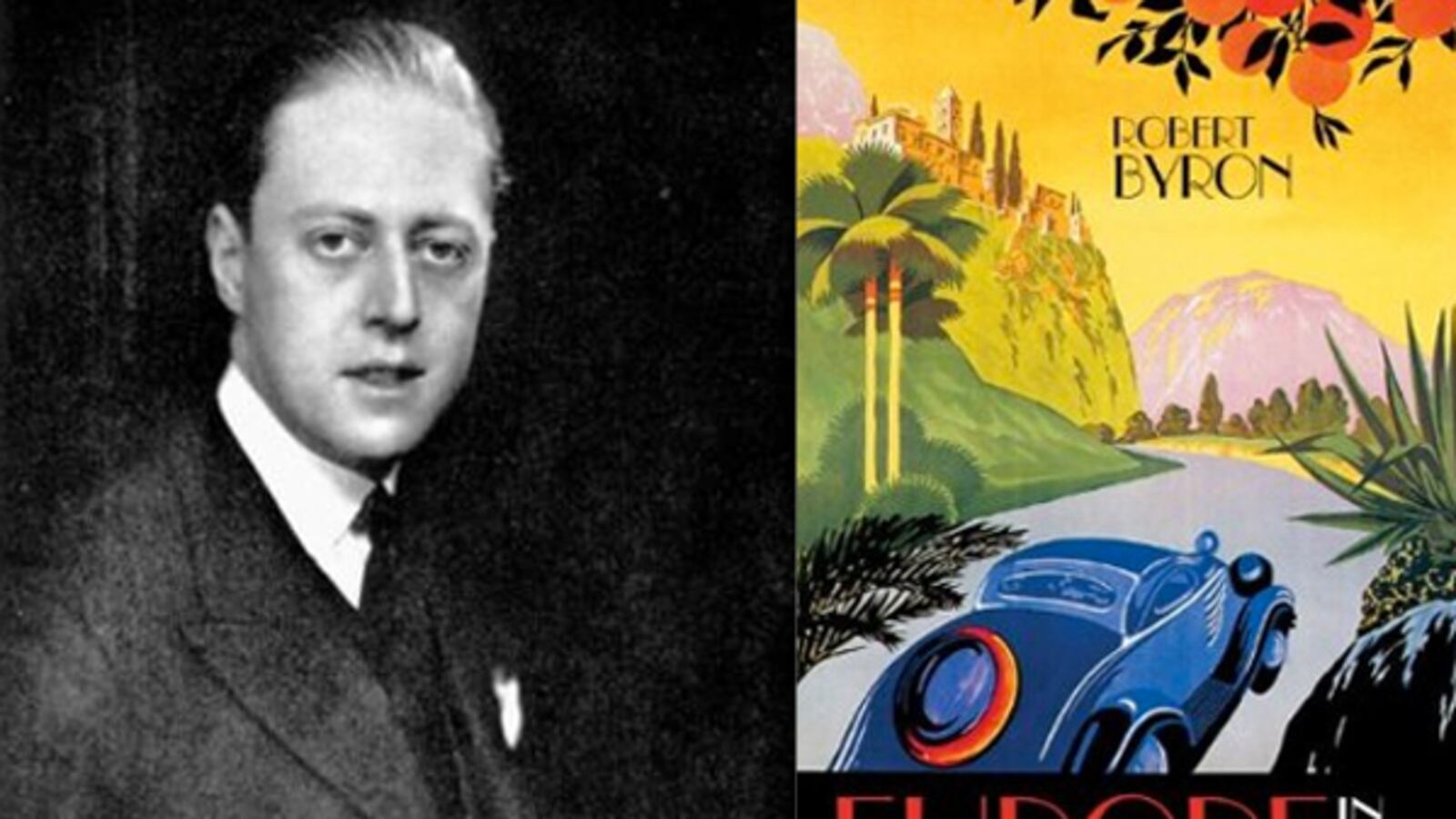

In 1925, after being kicked out of Oxford University for “misdemeanors” and mooching aimlessly around London, Robert Byron and two friends left for the Continent. As with his famous namesake before him, this would be a Grand Tour, but one done by car. Byron’s wry and informative account, Europe in the Looking-Glass, languished out of print for over 80 years. Now it has been rescued and republished by Hesperus, enabling us to rediscover Byron and catch a fascinating glimpse of post-war Europe and its relatively sunny calm before the sun blacked out.

The party’s car, a Sunbeam Tourer, was christened Diana, presumably in honor of the goddess of the hunt as they pursued their end destination of Greece—but of course Diana is Roman and the Greek name would be Artemis instead. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald had made a similarly lengthy overland trip five years earlier, from Westport to Montgomery, affectionately naming their old Marmon “The Rolling Junk.” Both chronicles involve frequent breakdowns and crashes and refreshingly un-macho admissions of inept driving. But while the Fitzgeralds lived beyond their means, Byron and his companions were the rich boys Fitzgerald was always so envious of, and could afford to splurge in palatial hotels and the finest restaurants. There is no evidence of obnoxious behavior, although they do encounter one petrol-pump attendant who disliked them so much that he refused a tip.

Byron travels by ferry to Hamburg, and on docking is instantly impressed by the politeness of the customs officials, a marked contrast with the “disobligingness” of their French counterparts. As the group drives south, stopping to sightsee and revel in the key cities, Byron provides further commentary on places and inhabitants: the Bavarian landscape is “bewitched” rather than bewitching; Bologna is “a seminary of temptation, a fount of loose-living”; Berlin, on the other hand, a ghost town till 6 o’clock, “has not sunk to the depravity of afternoon amusements.” Whether offering thumbnail sketches or broader brushstrokes, Byron’s critiques are bold, often forthright, but never xenophobic. If he is occasionally caustic it is due to being rubbed the wrong way by an individual. One overbearing American woman in Innsbruck “was middle-aged with a strong, efficient face, and had had, I hope, an unhappy married life.”

The highlight of the journey, for both reader and writer, is Greece. An ardent philhellene, Byron devotes the whole second half of the book to “the country of Socrates” and sees past the abominable roads to extol the merits of art and architecture. For a young and fairly immature 21-year-old, he exhibits a burgeoning talent as an art critic and historian. Pages of appreciation, which from a lesser writer would merely serve as perfunctory padding to the main fun, turn out to be the real gems here, embroidering the account but also elevating Byron to something more than a generic travel writer. He is solid on the wonders of Rome, acts as an expert guide to the cathedral at Esztergom, in Hungary, but truly excels in his evaluation of Greek sculpture in the Acropolis Museum.

Just as rewarding is his unwitting social commentary. The “Looking-Glass” of the book’s title offers a valuable peek into a cloistered, moneyed world and its attendant snobberies. Byron, the epicurean, eats partridges that are “newly-shot” and enjoys caviar “as large as frog spawn” and blue trout that “look like Ming pottery.” One friend orders venison stuffed with foie gras and covered with cherries, “but was too lazy to touch it.” The other refuses to arrive in Rome in flannel trousers. They hobnob with diplomats and minor royalty; a Naples hotel is decried for having a hall filled with “the English professional classes.” And yet, in the main, travel broadens the mind for Byron, to the extent that it helps him root out repellent displays of narrow-mindedness. In Italy he decides that fascism is in fact “a sort of boy scout regime; but instead of staves it carries revolvers.”

Europe in the Looking-Glass lacks the wit that infused Mark Twain’s A Tramp Abroad, Byron preferring pure observation to observational comedy. But it is all the richer for it. The book paved the way for Byron’s 1937 masterpiece, The Road to Oxiana, described by Bruce Chatwin as “a sacred text” that transformed the travelogue into art. We can only speculate as to whether Byron would have continued his wanderlust and produced more fine writing. He died in 1941, just 35, after a German U-Boat torpedoed the ship on which he was sailing as a BBC correspondent to Cairo. His body was never recovered.