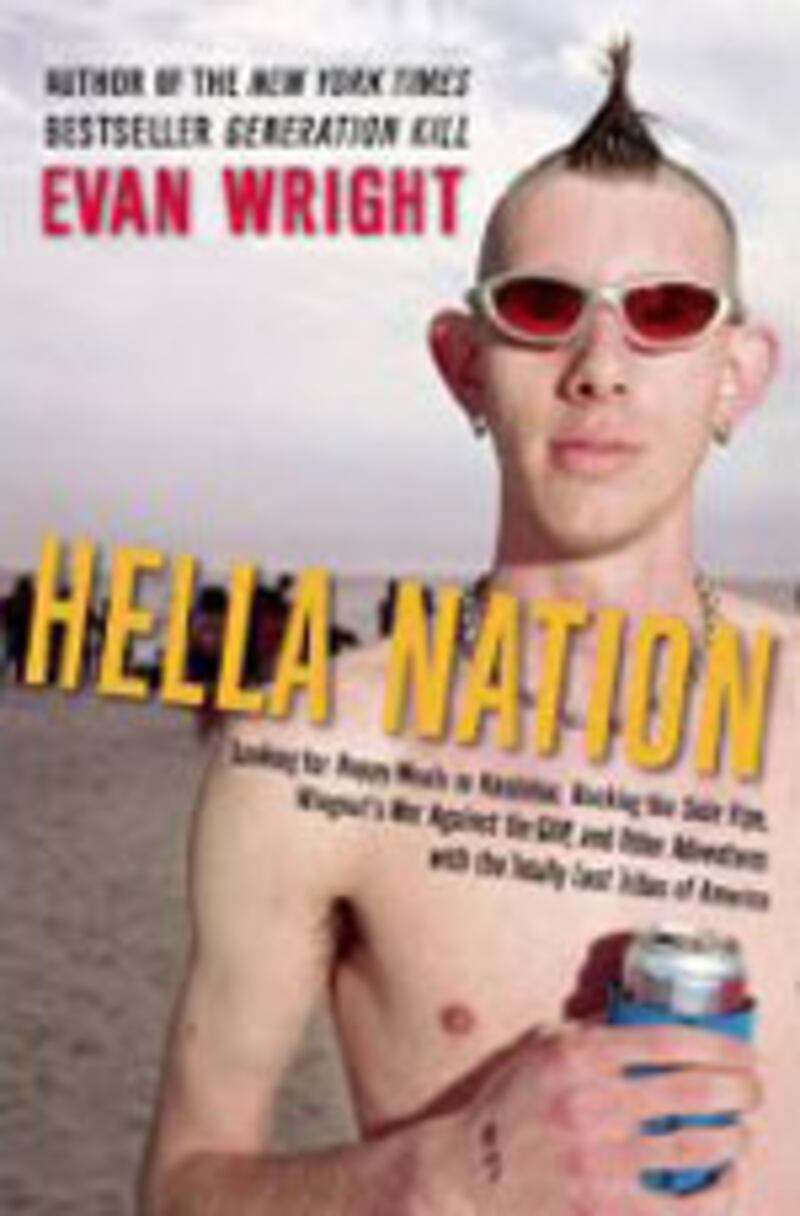

In Hella Nation, author Evan Wright, a Hustler writer turned Rolling Stone embedded war reporter, takes readers on a savage journey through the American underbelly and beyond. With characteristic Hunter S. Thompson bravado, Wright soldiers through fringe cultures populated by what he calls “rejectionists,” those extremists who have thumbed their nose at the American dream in pursuit of something more: anarchists, pornographers, con artists.

Read an excerpt of Evan Wright’s Hella Nation.

Wright’s bestselling Generation Kill spawned a HBO mini-series created by The Wire’s David Simon and Ed Burns. Now, Hella Nation pulls together the writer’s work as a mercenary reporter. Mixing memoirist self-vivisection (“Scenes From My Life in Porn” tracks his odyssey through the San Fernando Valley’s adult-movie business) with Vanity Fair exposé (“Pat Dollard’s War on Hollywood” follows one crazed, coke-snorting Hollywood agent’s fall from grace), Wright pulls back the curtain to reveal an America most of us keep a safe distance from. He spoke to The Daily Beast about infiltrating America’s hardest-to-crack subcultures.

In the introduction, you’re very upfront about your personal trips through the underbelly—working as a porn writer, struggling with substance abuse.

All my subjects are people who are struggling to fit in or to reinvent themselves, to find themselves. They’re runways, often, of one sort of the other. So I kind of wanted to write in the introduction about myself a little bit to explain why I have this affinity for those people. Because I see something of myself in them. I wanted to make it clear that in this collection of outsiders and freaks, I don’t look down at them. It’s not a condescending viewpoint. Because the reporter himself has struggled with that same role.

What is it about these subcultures resonates with you and with us? Is this the American dream gone wild?

It’s this realm where the American dream is sort of like a caldron boiling around, and it’s outside the conformity that dominates our culture. I talk about how these subjects are rejectionists, how we have this genius for co-opting differences: the anarchists in hoodies smash the Gap, and then the hoodies get co-opted and sold by the Gap. We have this genius for just fucking everything up. I look for people before they have been co-opted, or who can’t be co-opted, or who are fleeing from that co-option. It started with the porn industry, really. Leaving aside all the darkness, and victimization, and self-destruction, I always though it was so cool that the women, and some of the men, are out there being total weirdos and not caring. And I always saw something commendable about that. People who defied all social conventions. I like that in Dollard—the fact that the guy basically had a breakdown as a Hollywood agent and tried to reinvent himself by running away to Iraq.

What does “Hella Nation” mean?

Basically, it’s stupid slang. It was just a phrase used by one of the anarchists. It’s actually a meaningless phrase. It means fringes. I used a weird, almost meaningless slang phrase because it’s a part of America beyond conventional description. It’s the primordial ooze.

You talk about feeling more calm in Afghanistan as an embedded reporter than you were as a civilian in Los Angeles.

When I’m in a war zone or in a dangerous situation, I don’t know if I’m chasing a high or well-equipped for this because I’ve had a life of such chaos. There are certain stories I’ve done that I don’t know what the social value is. But other things—anarchy, crime, war—it’s important. I went there because I was like, Whoa, my country’s at war, and Iraqis are dying. And it’s a serious thing.

Generation Kill was turned into an HBO mini-series. What was it like to be on a set that replicated what was once your reality?

And to hang out with the guy playing me dressed in my shirt? It’s gross. It’s like that scene in Being John Malkovich, and you enter his head. It’s the ultimate narcissism. I found it gross. Is that weird? I don’t know.

You seem to have the ability to get people to do things in front of you that they might not normally do in front of others—drugs, screwing, scamming.

When I was a telemarketer, I couldn’t sell products, but I could get people on the phone, and this one woman, I was trying to sell her bogus computer supplies, and she was telling me how she got treated for cancer. My boss said, “Why do people tell you these things?” He wanted to harness that power to sell more bogus computer supplies. I don’t know why, but even before I became a reporter I noticed people would tell things to me. Like, Dollard’s behavior is a form of confession.

Stories abound that long-form journalism is a dying art, that magazines, in which many of these pieces first appeared, are a dying breed, that the screen has taken the place of the page.

A lot of these stories were covered in depth by television, and television completely missed the point. When I went to Afghanistan, television wrote about it like they were these American heroes avenging 9/11. My story was about these real stories. It’s not slamming the troops, but it’s who they really are. What I feel is that in an age dominated by moving-picture media, whether it’s television or YouTube, there’s a very important role for print. Because television cannot contextualize. TV saturates people with superficial understanding. And people can get saturated with one image over and over, and they think they know the whole subject. My work is an argument for the necessity of print. I believe in prose as a countervailing force to the weight and idiocy of image media.

"When I’m in a war zone or in a dangerous situation, I don’t know if I’m chasing a high or well-equipped for this because I’ve had a life of such chaos."

You were friends with David Foster Wallace. Were you surprised that he killed himself?

I wasn’t surprised because, I mean, actually there were a couple conversations we had a few years before where, you know, he said as a grim joke, “Well, if I continue in this state of mind …,” and then he did say, “I’d be hanging from a rope,” or something like that. On a super-functional level, he had a gallows sense of humor. It was actually a theme. When I heard about [Wallace’s suicide], I was surprised.

I once complimented him on some piece—he referred to his writing as his “shtick”—and he was very self-deprecating. He separated himself from the persona he had as a famous writer. So, when he died, I was very sad. Back to that gallows humor, knowing him pretty well, what I resent is all these stories where they’re all, “Oh, it was inevitable.” I look at it like he had a bad day. And as an accidental death. I know there were attempts before. A lot of people almost do this, and then they don’t. He was a really great person, a really extremely generous person, and it’s hard to see him as anything else but that.

Susannah Breslin is a freelance journalist and blogger. Currently, she is at work on a novel set in the adult-movie industry.