Both a character actor and a leading man, the chameleon-like Guy Pearce has played an array of roles that range from drag queens to repressed cops and macho action heroes. His most recent project, David Michôd’s The Rover, is a post-apocalyptic thriller shot in the Australian desert that premiered Sunday at Cannes at what was termed a “midnight screening,” even though the actual screening time turned out to be 10:30 p.m. And Pearce’s gripping performance as Eric, a bitter man at the end of his tether, has been universally praised. Most of the press has also been impressed with Pearce’s on-screen rapport with Robert Pattinson, who plays Rey, a terrified, vulnerable man who becomes Eric’s needy sidekick as they wander the barren landscape in search of a stolen car.

The Daily Beast met up with Pearce on Tuesday at Cannes’ Grand Hyatt Martinez Hotel. An amiable interviewee, he was more than willing to chat about acting technique, his wide range of screen roles, and much more.

Eric in The Rover is a much different role than the cop you played in David Michôd’s Animal Kingdom.

Totally, but I was excited to do this because I think he’s such an interesting director. I got into some discussions with him to learn more about this man named Eric that he wanted me to play because you really don’t get a sense of who he is in the script. It was important to get a sense of who Eric had been, because, as you see in the film, so much of who he was has been broken and stripped away.

I was wondering if you had constructed some kind of backstory for him.

It wasn’t even as literal or clear as being able to even call it a backstory. It was more of whether he had been a moral man, how much humanity he had, and what, just so I could see a little bit of a trajectory, his feelings were about the world around him collapsing.

You didn’t need an entire biography.

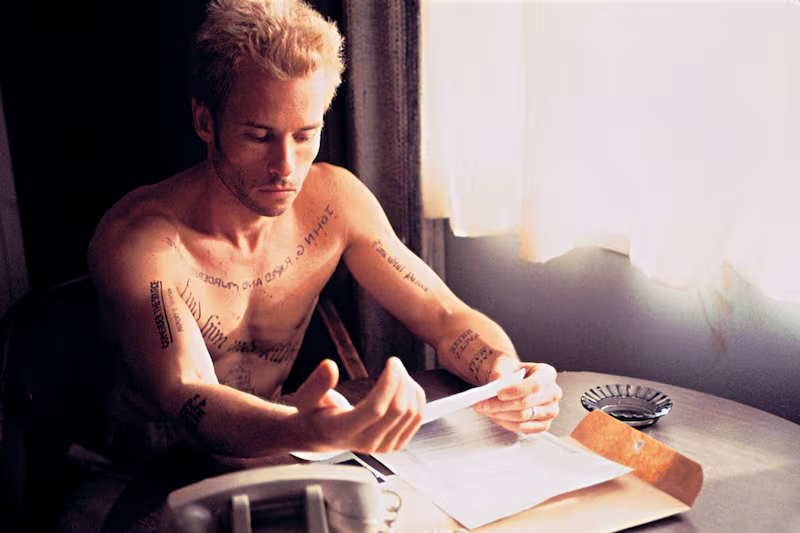

No, because we don’t live every day remembering that stuff. My focus was more on how to get the moments right at the time. It’s not unlike the role I played in Memento—obviously in Memento, I’ve forgotten everything so I just need to know about the character from moment to moment. But it’s just about your own confidence, feeling like you can step into that odd abyss confidently because you’ve at least explored what was there once and now it’s gone. On one level, Memento was one of the easiest jobs I’ve done since I didn’t really have to think about what went on before and what went on after.

So you could literally be “in the moment.”

That’s right. It was actually an interesting acting exercise. And, funnily enough, for this character in The Rover, although it’s very different obviously, he’s also someone who’s reached the end of the line and has nothing left to live for. He’s stripped of everything. It’s very bleak stuff.

“Ten Years After the Collapse” is the film’s opening title. Did the writers give you any idea what precipitated this collapse—perhaps a nuclear war or environmental devastation?

Nothing so specific, although I had an understanding of what those possibilities might have been. And we talked about it. But David didn’t seem to think it mattered. It’s a collapse, and if you respond to it emotionally (which is really the only way I respond to anything) you’ll get into the role, whether it’s a financial collapse, a war, famine, whatever. To me, it was probably a combination of all of those things. Actually, we’re seeing this sort of thing around the world already in various countries.

Your uneasy relationship with Robert Pattinson jump-starts the narrative.

Yeah, he was lovely and I was so impressed with what he did in the film. I was touched by the vulnerability of his character. He’s almost like a little kid or a vulnerable animal that needs to be looked after. You can’t help but empathize with him. And then it meant that I knew the power that I, as Eric, could exert over him—even in the few first moments when I speak to him. I just let him know that he means nothing to me. I guess I’m trying to deny what he does mean to me and I end up having to take him with me to find his brother. I just have to let him know that he means nothing to me, personally. It’s a way of him asking if we can connect and me more or less responding “absolutely no way.”

There’s almost a sort of Of Mice and Men dynamic between the two of you.

That’s right, particularly because of his Southern accent.

What’s interesting about your career is that you’re a character actor who can go from personal independent films to blockbusters such as Iron Man 3 and Prometheus.

Well, those are rarities for me. But the interesting thing about those two films is that I’m still playing roles that are as divorced from my own character as you find in something like The Rover. It’s funny that, even with Luc Besson’s Lockout, where I play the type of rather muscular, typically heroic sort of guy you get in a lot of movies, people asked if I was going to do more action films. I said, “No, this is as much of a step outside myself as anything else.” It’s still a character we’re creating.

So you always try to find a distinctive, personal angle to even seemingly stock characters?

Well, yeah, I can’t look at them as anything but three-dimensional characters. It’s true that the style might be a little nudge, nudge, wink at the camera and the situations might not be entirely realistic. It’s a funny job, really, when you look at it.

On the other end of the spectrum, you recently acted in independent filmmaker Liza Johnson’s second feature, Hateship, Loveship.

That was a lovely experience. Again, there was some sort of transformation in the character. I always find it interesting when you play characters that change because of the way other characters view them or impose demands on them—maybe because we’re all such sensitive creatures. I’m always affected by people around me and I think other people are as well. What’s interesting about The Rover is that Eric is so hardened that he’s determined not to be affected by Rob’s character. In Hateship, that character very quickly finds Kristin [Wigg’s] character very disarming. Certain characters don’t step outside of themselves and for this guy to come across this very odd character played by Kristin just suddenly opens up his world. A lot of what we shot didn’t end up in the movie, which was unfortunate.

The Proposition is an interesting film inasmuch as, like several films at Cannes this year, it’s sort of a neo-Western. And it’s noteworthy because of the fact that Nick Cave wrote it.

John Hillcoat had always wanted to make a Western and approached a few different writers. I think, if I have the story right, that he first hired an American writer and the script felt too American, like a classic American Western. And then Nick wrote it and maybe it worked because Nick’s originally from Australia. Or maybe Nick’s brutal approach gave John what he wanted.

Since you’ve been acting since you were a child, how has your technique changed over the years?

I’ve been acting since I was 7, but started professionally when I was around 17. I did a lot of theater as a child. It’s obviously changed because I didn’t actually make any films until I was around 21. My technique has changed because I feel more confident with what I’m capable of doing and more secure in stillness. I think one great lesson an actor can learn is how to be still.

That’s especially true for acting in films.

Yes, absolutely. That’s especially true when you’re in a massive close-up. I learned a lot of that on L.A. Confidential. Because I never went to drama school, Curtis Hanson was the greatest teacher I ever had.

So you basically learned to act on the job.

Yes, I really have and doing a lot of theater as a kid growing up and making it up as I go along. And there are also peak periods when you learn stuff and you try to implement those lessons on the job and have faith in what you can do and what you can offer. I tend to take a few jobs and then take a big break.

Do you get burnt out?

Well, it’s exhausting. It’s not life-threatening, or anything. But it’s exhausting. And I at least like to take some sort of break between jobs so I can regroup. But sometimes you need to regroup on a much bigger level. And then you’re ready to read again and you respond to things in a very intuitive and honest way. When I’m working too much, or reading too many things, I start to lose my perspective on what’s good and what’s not and what I’m actually responding to and why I’m responding to it. It’s very satisfying when you have some time off and you start to read again. As they say, the juices start flowing again.

You gave an interview some years ago when you talked about a phase in your life where you felt uncontrollably angry.

Yeah, that’s right. There was a point in the early 2000s when I was able to work a lot. It’s not until you get to that point that you realize how important those gaps in between jobs can be.

That allows you to refresh yourself?

Yeah, I’m much better now in managing both my mental and physical health.

Maybe it helps being married to a psychologist.

I think so. [Laughs] She’s a good woman.

The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert, in which you play a drag queen, was the first film of yours that garnered a lot of attention in the States.

I actually just got an email from the director Stephan [Elliott] because they were here with that film in Cannes 20 years ago. I couldn’t make it because I was doing a television show at the time and they wouldn’t let me go to share in the excitement. But we were reminiscing about that and I met for a cup of tea with Al Clark, that film’s producer. It was great to think back on not just that experience, but on why that film still resonates with people.

Why do you think it became such a cult movie?

It’s pretty colorful and out-there and was released at a time during the ’90s when people were willing to be more accepting of the gay lifestyle. The gay and transgender community latched on to that movie and held it up as their banner. The film’s great in a very heartwarming way.

It’s a very upbeat film.

It is, and it’s very brash, as drag queens can be. I don’t mean that in a negative way at all. They have a great sense of performance, bravado, and audacity. The film was very audacious—at least on a certain level. It’s certainly not confrontational, even though some people might have found it confrontational. It just came at a time when people were ready to say, “Yeah, this movie can be our poster boy.” But it does also stand the test of time. It was, I have to say, a very exciting thing to be part of.

We traveled the world publicizing it and I met every drag queen in the world. They all said that either my character, or any character they liked, was based on them. So it was a lot of fun, because it was something I hadn’t done before. And it was great for me in a work sense since it, as you say, opened up a lot of doors for me in the States. I got an agent there and was then able to audition for things. You know what it’s like. People see what you’re capable of and want to hire you. It’s very funny, though, that people sometimes ask, “Did you get L.A. Confidential because of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert? [Laughs] First, Curtis never saw it and he never wanted to see it. And, second, if he had seen it, he probably wouldn’t have given me the job.

There couldn’t be two more different roles.

Well, yes. The guy in L.A. Confidential is very repressed and conservative.

But L.A. Confidential was important for temporarily resuscitating film noir.

Yes, absolutely. And it was probably, unfortunately, the last film of its kind. They’ve tried to make some things like that, but the films haven’t had the impact of L.A. Confidential. That’s another film that’s stood the test of time.

Did you discuss the film with James Ellroy?

Yes, many times. In fact, we came here to Cannes in ’97 with that film and did a lot of panels. James is delightful. He’s really a character and a lot of people found him scary and intimidating. But I didn’t—and I’m often intimidated by people. He was just very honest. Funnily enough, he was doing a book tour in Australia when I had been cast, but before I came to the States to make the movie. He was doing a sort of show that involved him reading passages from some of his books. It was in Melbourne and I was sitting in the back of the audience with my wife. There was a question period and someone asked, “We hear L.A. Confidential is going to be made into a movie.” He replied, “Yes, and they’ve cast two Australians in the main roles—Guy Pearce and Russell Crowe.” The audience burst out laughing. They thought it was the greatest joke they’d ever heard and I sat there thinking, “Oh, my God, this is humiliating.” They probably thought he was making it up and those diehard Australian Ellroy fans probably were wondering why they would cast me in that role.

Some of the biggest Hollywood stars are now Australians.

Yeah, the funniest thing that Russell Crowe said to me was that we were the last two over the bridge before they took the toll off the bridge. It was about this time that casting directors began to discover a wealth of talent that came to Hollywood and took over. Cate Blanchett, Geoffrey Rush, and so on. Interestingly, at that time, when those actors came over, I at least knew who they were because I had seen them in many things at home. But now there are Australian actors popping up that I’ve never heard of. I feel like I’ve lost touch. I don’t even know who’s Australian or who’s not anymore. When those Marvel films came out, I had never seen Chris Hemsworth. At one time, everyone made at least one film at home before going off to Hollywood. Now they’re being plucked out of obscurity.

Australians seem very adept at American accents.

We all grew up watching American television.

When L.A. Confidential came out, many people might not even have known you were Australian.

Yes. The nice thing was that people would go, “Surely, you’re not the same dude that was in Priscilla, Queen of the Desert.” I’ve had a great run as far as being able to play a variety of different roles.