Just in time for Opening Day, here’s a gem about minor league ball in the South. It was written by the late Paul Hemphill, who was often called the Jimmy Breslin of the South. But that doesn’t do him justice. He was more than a brilliant columnist. His first book, The Nashville Sound, remains one of the great books ever written about country music, and his baseball novel, Long Gone, later made into a fun and now overlooked movie (it was shown on HBO the year before Bull Durham came out), is a treat. Leaving Birmingham: Notes of a Native Son, a memoir about coming of age in the South in the ‘50s and ‘60s is tough, honest, and moving.

Do yourself a favor and read Hemphill’s classic piece, “Quitting the Paper,” or his beautiful essay about his Old Man, or this story about Catfish Hunter. And next time you’re in a used bookstore, keep an eye out for one of Hemphill’s several fine collections.

This story, “The Heroes of My Youth,” comes from Too Old To Cry and is reprinted here with permission from Hemphill’s wife, Susan Percy.

Birmingham, Alabama

It was enough to make a man cry. Yes, indeed, quite enough. In another time, some twenty years earlier, there would have been a jaunty mob of four hundred red-faced steelworkers and truck drivers and railroad switchmen lined up at the four ticket windows—the soot and grease of a day’s work still smeared on their bodies, their eyes darting as they waited to get inside old Rickwood Field to take out their frustrations on the hated Atlanta Crackers—but now, hardly an hour before a game between the Birmingham A’s and the Jacksonville Suns, the place was like a museum. Five rheumy old-timers lolled about the one gate that would be open for the night. A broken old fellow who had celebrated his eighty-second birthday the night before sat on a stool in the lobby behind a podium stacked with scorecards, a position he had occupied for most of this century, calling out “Scorecards, get your scorecards” in the same froggy voice I remember from the first day I walked through these turnstiles twenty-seven years ago. On the cracked-plaster walls, needing a dusting, were the familiar faded photographs of the heroes of my youth: Fred Hatfield, Walt Dropo, Eddie Lyons, Red Mathis, Jimmy Piersall, Mickey Rutner, and, not the least, Ralph “Country” Brown. In contrast to the 1948 season, when the Birmingham Barons of the Class AA Southern Association averaged more than 7,000 paid fans per game, the attendance on this blustery June night in 1974 would come to exactly 338.

Quickly climbing the musty stairs to the executive offices, I sought out an old acquaintance. Glynn West had been fifteen years old in 1948, the holder of an exalted position in the eyes of the rest of us. On summer afternoons when the Barons were playing at home he walked the two miles from his apartment project to operate the scoreboard and supervise the kids lucky enough to be hired to shag baseballs hit out of the park during batting practice. Now, in his forties, he found himself general manager of a totally different Birmingham club, now called the A’s, fuzzy-cheeked chattels of the Oakland A’s farm system.

Seated behind a desk adorned with historic baseballs and photographs from the glory days, West wasn’t angry at anybody. “We used to get free publicity on the radio and in the papers,” he was saying. “It was a civic responsibility to support the home team back then. But last year we had to spend as much as we spent during an entire three-year period in the late forties just to draw twenty thousand people against the million we drew in 1948, ‘49 and ‘50.”

“Doesn’t anybody care?”

“Oakland cares to the extent that every dollar we take in means a dollar they don’t have to pay out. They’ll call and say, ‘Sorry, Glynn, but we’ve got to take so-and-so from you. We’re calling him up to the big club.’ What can I say? If it wasn’t for Oakland, I guess we wouldn’t have a club in the first place. When we were kids and some rain would come up, the fans would jump out of the stands to help spread the tarpaulin on the field. Now only one club in the league even has a tarp. We had to sell ours to help pay some bills.” He fiddled with a baseball once signed by a great Birmingham Barons team of the past. “Go find a seat if you want to. There’re plenty for everybody. Last year we had a promotion where the first one hundred people through the gate got a free copy of the Sporting News. Four people went away mad.”

The Birmingham Barons. With the possible exception of the one week I spent in the spring training camp of a grubby Class D club in the Panhandle of Florida during the mid-fifties, no experience in my life has been so profound as my undying awe for the hundreds of fading outfielders and flame-throwing young pitchers and haggard managers who wore the uniform of the Birmingham Barons during the decade covering the late forties and early fifties. It began on the late-August Sunday in 1947 when my old man, a truck driver, announced that we were going to see my first professional baseball game. The Barons, stumbling along then as threadbare members of the old Philadelphia Athletics farm system (they hooked up with the Boston Red Sox the next year), were playing a doubleheader against the strong Dodger-operated Mobile Bears at Rickwood. I fell in love with it all, at eleven years of age, the moment we walked up a ramp and saw the bright sun flashing on the manicured grass and the gaudy billboarded outfield fence and the flashing scoreboard in left-center and the tall silver girders supporting the lights. I would later read that Rickwood was regarded as one of the finest parks in the minor leagues. Nobody had to tell me that. Yankee Stadium could not have been more impressive to me. Taking our seats, we became one with the crowd: hooting at the umpires, scrambling for foul balls hit into the stands, needling the opposition, ooohing when a lanky Mobile first baseman named Chuck Connors towered a home run all the way over the right field roof (yes, the Chuck Connors, “the Rifleman”). Only Ted Williams had ever done that before, my old man told me, and one day I want to meet Connors and tell him about it. The Barons stumbled through a double defeat. The second game was shortened when disgusted fans began throwing their rented seat cushions onto the field at dusk.

From that day on and for the next ten years Rickwood and the Barons became the core of my life. Hurrying to deliver my seventy-eight copies of the afternoon Birmingham News (first, of course, I read sports editor Zipp Newman and his account of the Baron game of the night before), I would take the one-hour trolley ride to Rickwood in hopes of arriving early enough to see the players crunch into the parking lot around five o'clock for their pregame ritual. (One day I was stunned to see that a particular favorite was a gaunt chain-smoker.) In those days the big league clubs played their way up from Florida to begin the regular season, and during one spring exhibition between the Barons and the Red Sox I out-scrambled an old wino for a ball fouled into the bleachers by Walt Dropo, my hero from the previous Baron season who was getting his shot now in the big leagues. It was a ball that we kids in my neighborhood were able to keep in play for the entire summer. We called it the “Baron ball.” All night when the Barons were in, say, Little Rock, I would curl up in bed with the lights out and my radio under the covers to hear Gabby Bell’s imaginative re-creation of the game; not knowing for some time that Gabby was merely sitting in a downtown studio with a “crowd machine” and constructing his “live” account from a Western Union ticker tape. Occasionally my family would load up the car at dawn with fried chicken and oranges and potato salad and tea and ride over to Atlanta or up to Memphis to root the Barons through a Sunday doubleheader in the lair of the enemy. We always bought box seats next to the Barons’ dugout. One time, in Memphis, Barons pitcher Willard Nixon dropped a baseball in my lap because I was the most vociferous Barons fan in Russwood Park.

Nor did the interest wane during the off-season. There was always some Baron news in the Birmingham papers every day of the winter: The Barons had renewed their lease to hold spring training at Ocala; or the Barons had signed a fading major leaguer such as Brooklyn’s Marv Rackley or Bobo Newsom; or the Barons had sold a star from the previous season to a big league club and he was “thankful for the wonderful fans in Birmingham.” And then there was the Hot Stove League. Every Monday night in January and February, downtown at the Thomas Jefferson Hotel, a covey of locally bred stars such as Dixie and Harry Walker and Alex and Pete Grammas and Jimmy and Bobby Bragan would lollygag with fans and then watch a color film of the most recent World Series. And, too, you were likely to run into a Baron star on the streets in December—Eddie Lyons driving an ambulance, Fred Hatfield selling suits at Blach’s department store, Norm Zauchin running a bowling alley—for these were the days when a player might settle down with one minor league club for the five or ten years left of his career.

Looking back, I am convinced that during those years the Southern Association was the best all-around minor league in the history of baseball. The eight towns were paired off into four perfectly natural civic rivalries—Atlanta vs. Birmingham, Little Rock vs. Memphis, Nashville vs. Chattanooga, Mobile vs. New Orleans—and it was, indeed, regarded as one’s civic responsibility to support the home team. Twice my old man and I stood for six hours behind a rope in center field with two thousand others (the park seated sixteen thousand then) to shout obscenities at the Atlanta Crackers. The nearest major league action was in St. Louis. All of the clubs in the Southern Association had strong working agreements with big league organizations, but they also had a certain amount of financial autonomy. After one particularly successful season, the general manager of the Barons—a feisty Irishman named Eddie Glennon—magnanimously sent a check for five thousand dollars to millionaire Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey “in appreciation for what the Boston Red Sox organization did” to help the Barons.

There simply wasn’t anything better to do during summer nights in those Southern cities at that time in American history. There was no air conditioning. There was little television. There were no nightclubs, thanks to the Baptists, and there was scant affluence to create boating and nights at fancy restaurants. And so, in Birmingham and Chattanooga and those other bleak workingman’s towns of the postwar South, baseball was the only game in town. Fans passed the hat around the box seats after a meaningful performance to show their appreciation in dollars and cents. Businessmen offered free suits or radios or hundred-dollar bills for home runs or shutouts or game-winning hits. Kids, like young Paul Hemphill, went speechless in the presence of Fred Hatfield the third baseman. Citizens offered the use of their garage apartment, rent-free, to whoever happened to be the Barons’ shortstop that year. In this atmosphere the Barons of 1948, with 445,926 paid customers and a total attendance of some 510,000 for seventy home dates, outdrew the St. Louis Browns of the American League.

***

With infield practice over, Harry Bright stood smoking a cigarette in the runway leading from the playing field to the newly remodeled A’s clubhouse while his young players changed sweatshirts and relieved bladders and played fast games of poker. Bright is forty-five now, a baseball itinerant since the day he signed a contract with the Yankees at the age of sixteen. He knocked around the minor leagues for twelve years, hitting .413 one year in the woolly West Texas-New Mexico League, before getting in eight big league seasons as a utility player. This was his ninth season as a minor league manager, his second straight with Birmingham. I remembered when he played for a great Memphis Chicks team in the early fifties, a club managed by Luke Appling and stocked with several veterans who had leveled off at Class AA.

“That was ‘53,” he was saying, leaning against a concrete wall in a gold-and-green uniform identical to that of the parent Oakland A’s. “I was making three hundred fifty dollars a month.”

“How did you feed your family?”

“With a lot of peanut butter.”

He flipped the cigarette away. “Actually I picked up a lot on the side that year. You remember that laundry that used to pay two hundred dollars for every home run hit by a Memphis Chick?”

“The Memphis Steam Laundry.”

“Right.”

“Had their plant behind the center field fence.”

“Right. Well,” said Bright, “I hit fifteen homers that year and fourteen of ‘em were at home. Somebody said the laundry shelled out twenty-one thousand dollars in home run money that year. We had a lot of power that year.”

Bright’s eyes would shine as the old names and stories were passed around. Ted Kluszewski, Jimmy Piersall, Carl Sawatski. The train travel, the horrendous 257-foot right-field fence at Sulphur Dell in Nashville, the wild extravaganzas promoted by entrepreneur Joe Engel in Chattanooga. The low pay, the poor lights, the fleabag hotels, the maniacal fans, the hopelessness of it all. But Harry Bright has, by necessity, quit living in the past. “It’s my job now,” he said, “to bring these kids along and prepare ‘em for the big club. You know. Teach ‘em the ‘A’s way of baseball.’ It would be better for them if more people came out for the games, because a crowd gives you an edge and makes you go harder. But people won’t buy minor league baseball anymore. They can see the real thing, the big leagues, on television. What the hell.” His club was slumping into last place. Bright pulled the lineup card from his hip pocket and trudged out to meet the umpires. Hardly anyone noticed.

I should have seen the first signs of demise as early as 1950 when my mother came to see my YMCA team play on a dusty sandlot one day and commented afterward that she would rather watch “boys I know” than go to Rickwood to witness “boys from Chicago and places like that,” no matter how good the latter were. When the Little League program came along, involving every kid in America with any propensity whatsoever for the game, it robbed the minor leagues of the business from those kids’ parents. Those parents were the hardest of the hard-core fans. Then along came television and air conditioning and affluence (and then the Atlanta Braves, in the case of the South), and one day the minor leagues simply died in their sleep.

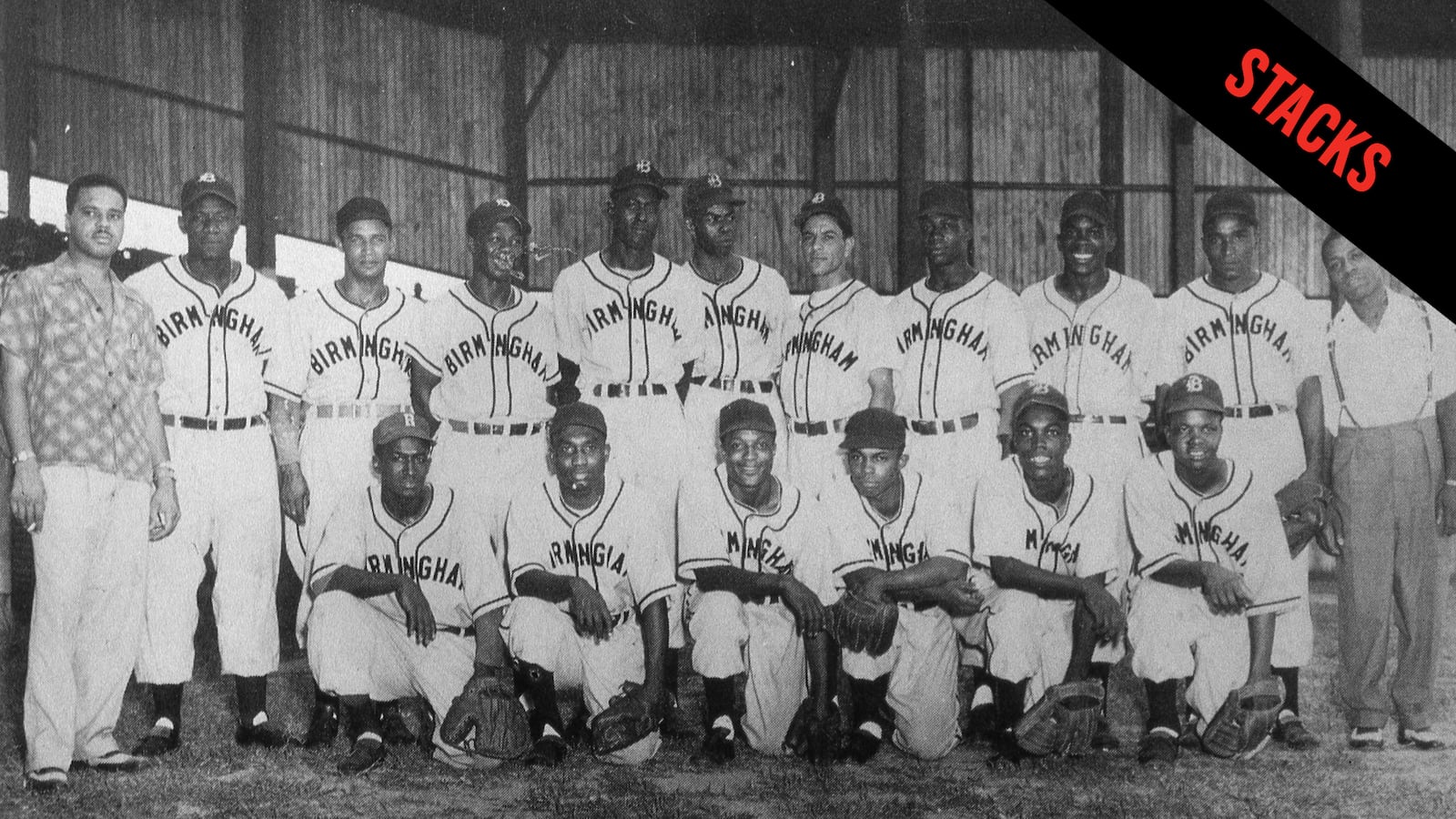

The state of Georgia once had twenty-two minor-league towns; now it has only three. In 1973, the Southern Association as a whole drew two thousand fewer fans than Birmingham alone drew in ‘48. This season of ‘74 there is no radio broadcast of Birmingham A’s games, and the baseball writer for the morning paper is the thirteen-year-old son of the sports editor of the Birmingham Post-Herald. Rickwood Field is as pretty as ever, although some of the uncovered bleachers have been taken down. These bleachers were once called the “nigger bleachers,” and it was below them that a precocious teenager named Willie Mays once made incredible catches for the Birmingham Black Barons of the Negro American League before baseball finally desegregated. Now high school football and baseball games share billing with the A’s on the lush green turf of Rickwood where once Eddie Lyons and Walt Dropo and Gus Triandos and Country Brown and hundreds of my other youthful heroes trod.

One of the most prominent billboards lining the outfield fences at Rickwood these days is one reading WHEN VISITING ATLANTA SEE THE BRAVES. As the game went on that night, Harold Seiler squinted out to left field and tugged at his A’s cap and patted the knee of his wife, Mabel, sitting beside him in their third base box seats, not knowing quite what he could add to the story of the death of the Birmingham Barons. Hal Seiler owns a paint store in Birmingham and has been known, as long as anybody can remember, as the city’s number-one Baron booster. Nearly every night of a Birmingham home game for some three decades, he and his wife have been there. One night last year he suited up and actually managed the A’s through one of those insufferable late-season “let’s get it over with and go home for the winter” exercises.

“Coached third base, even changed a pitcher,” he said.

“You win?”

“Won it, four to one. Bright panicked and took his job back.”

Minnie Minoso’s son, a fine-looking Kansas City prospect playing right field for Jacksonville, cut down a runner trying to go from first to third and got applause from the Seilers. A black dude in the grandstand behind Seiler began a funky dance in the aisle, wildly thrashing about in a cream-colored suit. “Cat comes every night, too, wearing a different outfit every night. Hell, I bet I know the first name of two hundred of these people. It’s like a family reunion out here.”

“Zeb Eaton. You remember Zeb Eaton?”

“One that got beaned.”

“What year?” I said. Trivia now.

“Nineteen and forty-seven.”

“You here that night?”

“Here? Rickwood? I was always here.”

“Zeb Eaton.”

“Me and Mabel were right here. We heard the thud of the ball hitting his head. Ballpark sounded like a morgue. I helped pass the hat and raise money for Zeb’s hospital bill.”

I said, “Joe Scheidt. You don’t remember Joe Scheidt.”

“Joe Scheldt,” said Hal Seiler. “Crazy. Absolutely bananas. Fast as a rabbit, though. Let me give you one. I remember ‘em all. I bet you don’t remember Edo Vanni.” I told Seiler that I certainly did remember Edo Vanni, an outfielder who passed through briefly as a Baron. Seiler was crestfallen. “I didn’t know anybody remembered Edo Vanni,” he said. “As a matter of fact, I didn’t know anybody remembered the Barons.” A pinch hitter named Pickle Smith was announced for Jacksonville. “Pickle,” yelped Seiler. “Pick-le. Hey, that ain’t no pickle, that’s a gherkin. C'mon, you gherkin, back in the bottle. Let’s show the Gherkin something out there….” The last true baseball fan, Harold Seiler, of Birmingham, Row Five, Box AA, Rickwood Field, smiled like a cherub as Pickle Smith struck out on three straight pitches.