She was murdered because she wouldn’t end the affair she was having with the professor who was also her mentor. Or he killed her because she was about to expose the fact that his claims about the importance of an archaeological dig he was working on were bogus. Or maybe he killed her because he was trying to protect his bid for tenure, and she was in his way.

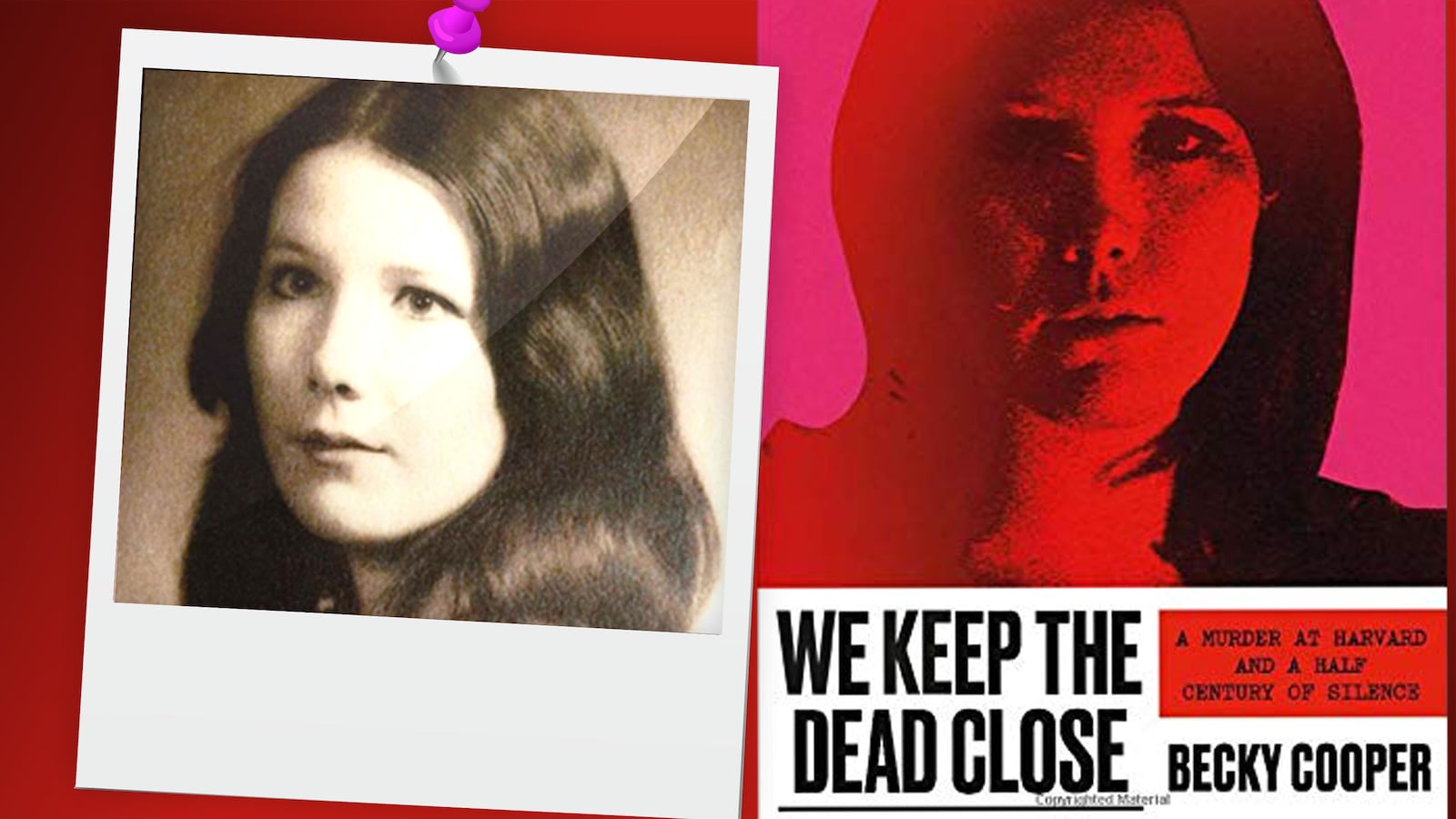

Fifty years after she was found murdered in her apartment in January 1969, Harvard graduate student Jane Britton’s unsolved killing had become a sort of urban legend. But it was a legend known only to very few people.

“It was actually frightening, almost nobody outside the archaeology department knew about this, but inside the department, almost everyone knew it. It was alive, but isolated,” says Becky Cooper, author of We Keep the Dead Close: A Murder At Harvard And A Half Century Of Silence, a book about her attempt to solve this coldest of cold cases.

Cooper first heard the story during her junior year at Harvard in 2009: how Britton was bludgeoned to death in her off-campus apartment, her body covered with fur blankets and red ochre thrown on her, a re-creation of an ancient burial ritual. She soon discovered that the building where Britton had been killed was owned by Harvard, which had failed to upgrade its security (there were no functioning locks on the main doors). And she became aware of the rumors that the story had been silenced, that the school was determined to control the narrative.

Cooper quickly created a psychological bond with the dead woman, who was described by those who knew her as intense, obstinate, wild, “sort of a combination of Groucho Marx and Dorothy Parker.”

“I thought that despite the decades that separated us,” says Cooper in her book, “I had found a companion in my loneliness in her.”

We Keep the Dead Close is hugely readable and exhaustively researched, but it is much more than a true crime book. Cooper’s interests run far afield, and include a look at the power plays and misogyny of academia, police incompetence, who Jane Britton really was, and the nature of truth itself. But it is her look at the Harvard anthropology department—not exactly the kind of subject matter you’d expect to find inherently fascinating to outsiders—that provides the true core of the book.

“The book traces the evolution of my thinking about academia, as a kind of utopia of knowledge discovery to something akin to a feudal society,” says Cooper. “The baked-in structural inequity in academia, where structure depends on a few invincible tenured professors, many of whom are white and male.”

So, zeroing in on the Cambridge behemoth, Cooper discusses its history of misogyny and sexism, noting that in 1994, only 5 percent of its science faculty was female; that during the early 2000s presidency of Larry Summers, who publicly stated that men do better than women in math and science because of biological differences, tenured jobs offered to women dropped from 36 percent to 13 percent; and that even when women advance higher in academia, many silently drop out: 87 percent of all Harvard anthropology department dropouts over three decades were female.

“I was surprised by how much less has changed than I would have guessed when I started working on the book,” says Cooper. “The misogyny is definitely less overt, but just because it’s less overt now doesn’t mean it’s any less pervasive or pernicious. This is a disease that academia doesn’t want to admit it has.”

Connecting all this to anthropology, Cooper goes into detail about the Iraqi dig that was a key element in Britton’s field experience, explaining that the remoteness of field work and the dependence on a male supervisor can increase a female student’s vulnerability, that expeditions can significantly impact the career trajectory of young female professors, and that there is “the idea of an archaeologist as this hyper-masculine, swaggering explorer.”

That certainly seems to be the case with the various murder suspects who appear in the book. There’s the former wrestler with the violent temper whose baby Britton aborts. The one with a violent disposition whose female partner mysteriously disappears on a Canadian expedition. And of course, everyone’s favorite bogeyman, the mentor/professor who was still at Harvard when Cooper sat in on his class in 2012.

But none of them did it. The crime was finally solved through DNA testing (no spoilers here), and the book seems to show a real sense of disappointment at the result on Cooper’s part. “The complicated mix of heartbreak, guilt, betrayal, shock, and disbelief when I learned the identity of the killer is hard to get into without spoiling the ending,” she says. “I will say it had a lot to do with the fact that just as I was getting ready to let go of old stories, I felt hit with another.”

Part of this had to do with Cooper’s intense, even obsessive, identification with Britton, which she had to reckon with after interviewing the murdered woman’s brother who, “in his portrayal of Jane, Jane was refusing to be me. My discomfort about that fact forced me to confront that I had too strongly identified with Jane, and that my blindness to the ways in which we differed was denying her complexity.”

And that, in a larger sense, is what the book is about—how we tell our stories. Cooper points out that after spending so much time in the archaeology world, she came to realize that there were two kinds of archaeologists: the scholars who were data-driven, and the ones who used facts to tell stories—or, as one of the Harvard suspects says in the book, “all archaeology is the re-enactment of past thought in the archaeologist’s own mind.”

This leads Cooper to question whether it is even possible to tell a responsible story about the past, given how facts are interpreted in the service of the storyteller. “There are no true stories,” she says in the book, “there are only facts, and the stories we tell ourselves about those facts.”

So We Keep the Dead Close is, ultimately, a fascinating, fact-driven work seen through the prism of one Becky Cooper, one that says as much about the author as its subject. “I hope one of the conclusions of my book is that each of us should try our best to do the very unsexy thing of trying to find the facts,” says Cooper. “Stories are ultimately reflections of the storyteller—and we can each be better about being self-critical about the underlying biases and assumptions we’re adhering to, that make those particular stories so seductive.”