The photos are both nostalgic and eerie. Steep staircases lead to nowhere. Brick walls suddenly end. A pinprick of light shines through at the end of dark, rocky tunnels. The surf of the Pacific Ocean crashes into the rocky ruins dotted with a red sign of caution, “Cliff and surf area extremely dangerous.” Just in case that warning wasn’t dire enough, it gets specific: “People have been swept from the rocks and drowned.”

This striking scene nestled in the Golden Gate Recreational Area is all that is left of what was once the Sutro Baths, a grand complex of public baths, recreational areas, and a mini natural history museum that San Francisco millionaire Adolph Sutro built in the late 1800s.

At the height of its popularity, the bath area alone could accommodate over 10,000 guests; now the area has been allowed to go wild, to return to nature with mere traces of its history left behind for those who dare to explore.

Today, only youngsters get that familiar feeling of summertime glee at the prospect of visiting one of the overly chlorinated rectangles of bath water surrounded by concrete that most cities call public pools.

But over a century ago, Sutro had another idea for how to bring the community together—a public water paradise. As the old timers are so fond of saying: they don’t make public pools like these anymore.

By the time Adolph Sutro got the notion in his head to construct a massive recreational area for his fellow citizens, he had already had more than his share of success. A German immigrant, Sutro had made his fortune in the mining industry before settling down in San Francisco. Once there, he continued adding to his cache by diving into the growing city’s real estate market.

In 1894, Sutro decided to go full civic, serving a two-year term as mayor of San Francisco. Two years later, on March 14, 1896, the massive public project he had conceived and bankrolled—Sutro Baths—opened its doors. The project cost $1 million and covered three acres of land on the Pacific Coast.

When Sutro first bought the land, he originally built a small tide pool on the site to indulge his own interest in studying ocean life and the natural world. But he decided his joy in the area needed to be shared, so he conceived of the Sutro Baths as an inexpensive recreational area that all San Franciscans could enjoy.

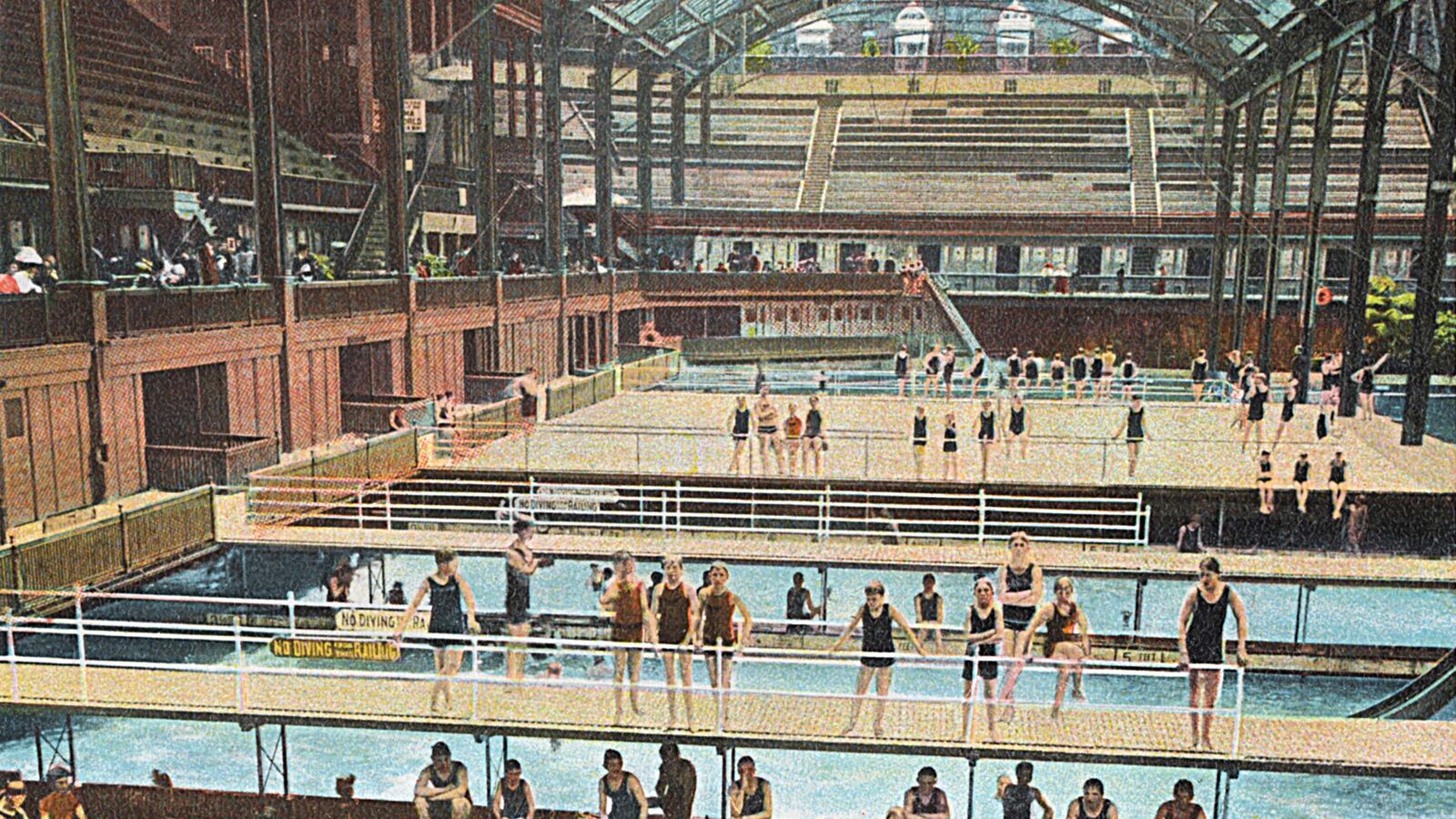

At its core, the Sutro Baths was a swimmer’s paradise. The giant complex became the “world’s largest indoor swimming establishment,” an award that was well deserved given the list of indoor water amenities on tap.

During a visit to the Sutro Baths you could take advantage of seven swimming pools, the largest of which was filled with freshwater while the other six of varying sizes were saltwater baths that provided dips of varying temperatures.

“No baths so large, so expensive, or so perfect in every detail have ever before been built in America, or, perhaps, in the world,” The New York Times reported in 1894. “Imagine Madison Square Garden filled with sea water to a depth of from 4 to 10 feet, and you can have a conception of the main tank.”

The building was constructed flush against the ocean, and the incoming waves from the Pacific could be heard crashing against the structure from the largest of the pools. It was a very convenient location given that this rival body of water actually served a crucial function for the Sutro baths.

At high tide, the Pacific Ocean filled the smaller, saltwater pools where they were heated to the temperature required for each. When the tide was out, pumps brought the water in from the ocean.

The public pools weren’t just for lounging; diving boards and trapezes were available for all San Franciscans to practice their water acrobats. The facilities could host 10,000 bathers at one time who took advantage of the 20,000 bathing suits and 40,000 towels that were available for rental. If swimming wasn’t your thing, you could observe the action from the stadium seating.

In addition to playing at the pools, the massive structure also contained natural history exhibits and art galleries (including Egyptian mummies). There was a performance space that could host orchestras and other shows, as well as a dance hall and a restaurant.

“A small place would not satisfy me. I must have it large, pretentious, in keeping with the Heights and the great ocean itself,” Sutro is reported to have said.

When the Sutro Baths debuted, they were quite the hit. But they never quite made it financially. Despite the flock of San Franciscans who visited—Sutro even built a rail line to help people travel there from the city—it never sat comfortably in the black. A site that was this advanced and this exposed to the ocean required a significant amount of expensive repairs and upkeep.

One disaster it did weather well was the 1957 earthquake. According to an account in The New York TImes, “although great numbers of windows in San Francisco, Daly City and other nearby communities were broken, every one of the 100,000 panes at Sutro Baths, on the San Francisco ocean front, survived the tremors,” despite the fact that it sat “virtually at the edge of the San Andreas Fault.”

Sutro died only a few years after the baths opened, and his family tried to uphold his legacy for the next several decades. But the Great Depression took a serious toll on attendance, and in an effort to appeal to the changing times, Sutro’s heirs changed a majority of the public baths into an ice skating rink. In the end, even that change couldn’t save it. The family sold the property to developers in 1964. The former public water paradise was condemned to become mundane condos.

That is, until disaster struck. Two years later, after bulldozers had already begun wrecking their havoc on the structure, a fire broke out. The cause was ruled arson, although it was never determined if there was an ulterior motive. The site was reduced to ruins and the condo project was scrapped. The area would eventually be incorporated into a national park, the Golden Gate Recreational Area, and the haunting remains of the Sutro Baths preserved for hikers forever.

And haunted, they allegedly are. Since the fire, visitors to the ruins have reported strange sights and weird goings-on. Some say candles are blown out or thrown into the ocean. Others report spotting weird figures in turn of the century bathing garb that vanish when approached.

But whether you’re roaming the ruins alone or have some unexpected company, the message is clear: “Caution: cliff and surf area extremely dangerous.”