The Haunting of Sharon Tate is a movie about fate. Tate, played by Hilary Duff, is kept awake at night by visions of her impending death. Just like the Haunting audience, Tate knows that her murder is inevitable. It happened years ago—a semi-random, terrible slaughter orchestrated by Charles Manson and his cult family. What Manson conceived of at the time as deliberate chaos is now just history—a horrible thing that happened because an evil person willed it into being. Sharon Tate’s death did not usher in the apocalypse, and Charles Manson died in prison. It’s a tragic, pointless story, and it’s the one that Sharon Tate will always be remembered for. The Haunting of Sharon Tate imagines a world in which the actress’s death, and therefore her legacy, was narrowly avoided, imbuing the star with the foresight and agency to predict and prevent her own murder.

Director Daniel Farrands’ conceit reportedly traces back to a tabloid’s claim that Tate had a premonition that she would die a full year before the Manson family invasion. The image of an ill-fated starlet plagued by visions of a disturbing future is a vivid one, but one that a basic sense of courtesy and propriety would prohibit most people from converting into a feature-length film. It’s a thought experiment best suited for private contemplation: a young Sharon Tate pregnant with premonition, bewildered and terrified, as a vision of Lizzie McGuire star Hilary Duff playing her in a poorly written 2019 snuff film flashes before her eyes.

Throughout the film, Tate repeatedly wonders if fate can be tampered with, or if we’re all “slaves to our own destiny.” The Haunting of Sharon Tate marks a fate so strange, unpredictable, and cruel that no one ever could have seen it coming—but someone probably could have, and should have, stopped it.

Tate’s sister Debra has deemed the film “classless,” and that lack of support from the murdered subject of the film’s family really says it all. Watching an unauthorized Sharon Tate film makes you feel just about as icky as you’d expect. Rather than attempting to alleviate the inherent grossness of dramatizing a vile murder, The Haunting of Sharon Tate leans right in, all jump scares and unapologetic snuff-film vibes. Not content to just ratchet up the scary soundtrack and run right through the prop blood supply, the film’s premise demands that the audience watch the murders over and over again.

In The Haunting of Sharon Tate, the Valley of the Dolls actress arrives at her Benedict Canyon home 72 hours before her death. She becomes increasingly distracted by nightmares and visions, which are dotted with waking clues. There are strange envelopes from “Charlie,” a guy who’s been coming around the house looking for an old tenant. Tate learns about Charlie’s followers, his “family,” and her rapidly increasing paranoia is triggered by a dead dog and two waifish, wide-eyed girls who come too close to her on the walking trail. Naturally, her live-in friends Abigail Folger (Lydia Hearst), and Wojciech Frykowski (Pawel Szajda) think she’s going insane (although Abigail does concede that they’ve been having some weird people over, and smoking some pretty dank weed). Tate’s husband, Roman Polanski, is off working on a film, but Sharon is convinced that he’s having an affair. She creeps around the property in set loops, from the nursery to the window, from the bedroom to the door. Sometimes it’s a nightmare, running through the particulars of her death over and over again. Then suddenly she’s awake, a hand on her stomach, with a distantly-vexed expression suggesting physical discomfort but also, I would like to think, the pain of reciting such horrible dialogue.

When she isn’t randomly waxing on about fate and chance, Tate is awkwardly teasing her ex Jay Sebring (Jonathan Bennett) with totally normal comments like, “Well you didn’t become stylist to the stars by just running your fingers through their hair,” or she’s hilariously whispering “Damn you, Roman!” to an empty bed. As the spooky situation continues to devolve, Tate repeats a number of warnings and unconvincing, stock-scared responses like, “Something is very wrong inside this house”—understandable, coming from a woman who’s been dying for three days, but not very conducive to the pure-terror vibe the film is clearly going for.

This wooden acting, and the relationships that come off as fake and far-fetched as the plot they’re cycling through, are all consequences of a film that prioritizes cheap scares over convincing characters. At the end of the film, when Tate’s premonitions finally come true, she’s run through them so many times that she knows how to stop it. She fights back, stabbing and cursing out her assailants, and lives to haunt her own fate.

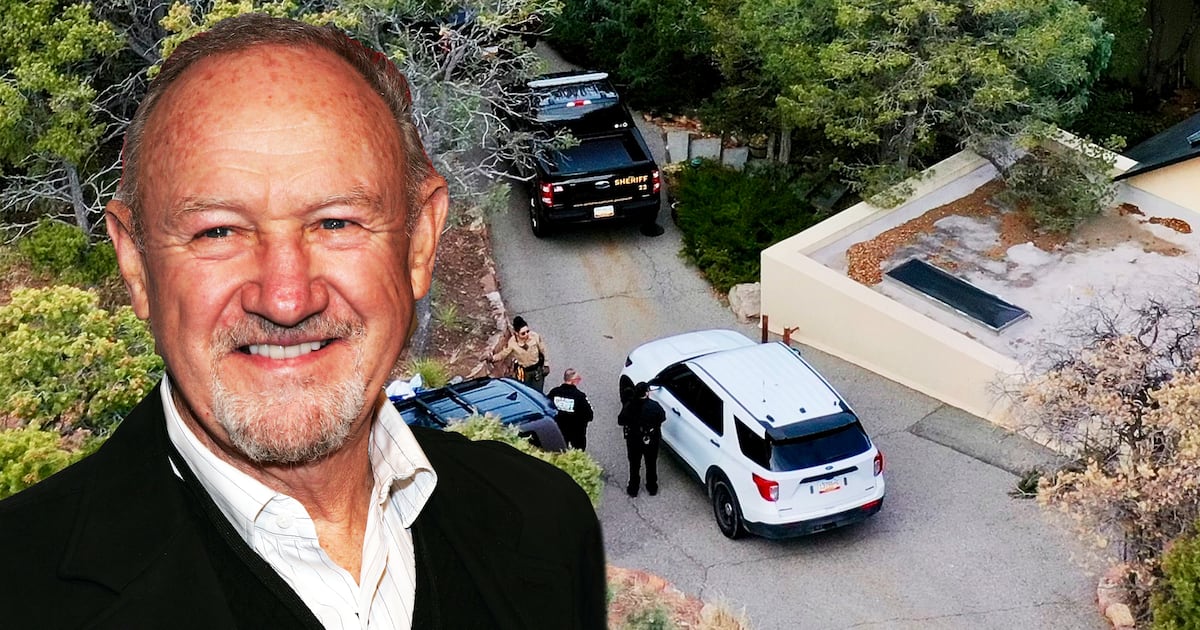

In one of the final scenes, a bloodied Tate returns to her house the morning after, seemingly on another plane of reality—she sees the cops, the corpses, the newspaper headlines. She walks away from all of it. But this show of agency, after a night of very spirited self-defense, is undermined by the Tate who we see onscreen. Duff plays the young actress as a tragic Hollywood starlet—not a pregnant, terrified, and totally exasperated human being. She’s vacant and beautiful, with permanently pursed lips and a knockoff Christian Louboutin accent (fancy, expensive, but just off). Occasionally sounding inexplicably British is about the only interesting thing that Duff’s Sharon Tate does. Scary dreams do not a multi-dimensional character make. Starring in a movie that epitomizes our grotesque cultural obsession with dead girls, Tate comes across as a pretty projection. The film about defying fate finds Tate relegated to her perpetual post-mortem role of tragic enigma. Sharon Tate might as well be a ghost in her own life story, for how little we see of her here.