HONG KONG – The president of Interpol is missing. While the international law enforcement organization based in Lyon, France, has yet to comment, French police have opened an investigation into the disappearance of Meng Hongwei. His wife reported that he has not been seen since late September, when he left Lyon for China.

Meng has been the president of Interpol, one of two top positions in the organization, since he was elected by the group’s general assembly in 2016, but that’s not the only hat he wears. Meng has been the vice minister of public security in China since April 2004. And there is widespread speculation he ran afoul of the Communist Party leadership. What isn’t clear is why or how.

Under Meng’s watch, China has, at times violently, cracked down on labor activists, lawyers, women’s rights activists, and LGBT rights advocates. The security measures in Xinjiang, which is home to the Turkic Uyghur people, have become increasingly harsh, with the local population facing mass incarcerations of people believed to harbor “politically incorrect” ideas.

Controversy was kicked up by rights groups when Meng took up his title in Lyon: would a career politician and security official from China skew Interpol’s supposedly neutral and apolitical mission?

Would he, in fact, abuse the powers of the global police organization and follow Beijing's orders, hunting down Chinese dissidents, critics, and political opponents who have managed to find new homes outside of the People's Republic?

Those worries were not unfounded. China has a history of abusing Interpol’s “red notices” system, which comprises formal requests to arrest fugitives for extradition. “Red notices” are valid within the borders of 190 member countries of Interpol, though each country has the right to decide whether it will act on the “red notices” issued by Interpol, and no country can be forced to make an arrest.

Last year, at the request of Beijing, and with Meng at the helm, Interpol issued a “red notice” for the arrest of Chinese tycoon and Mar-a-Lago member Guo Wengui after he made allegations of corruption at the apex of the Chinese Communist Party and fled to the United States. (The arrest warrant for Guo in China, which was issued in 2014, is for bribing the country’s deputy spy chief.)

In a speech given at the 86th Interpol general assembly hosted in Beijing last year, Meng painted a grim picture of our world, saying that “problems and conflicts are growing” and that “terrorism haunts the globe.” True enough. But these also are phrases often invoked by the Chinese government to justify the harsh treatment of Uyghurs, Tibetans, and outspoken dissidents. At the time, according to Chinese state media, China was involved in about 3,000 active Interpol investigations.

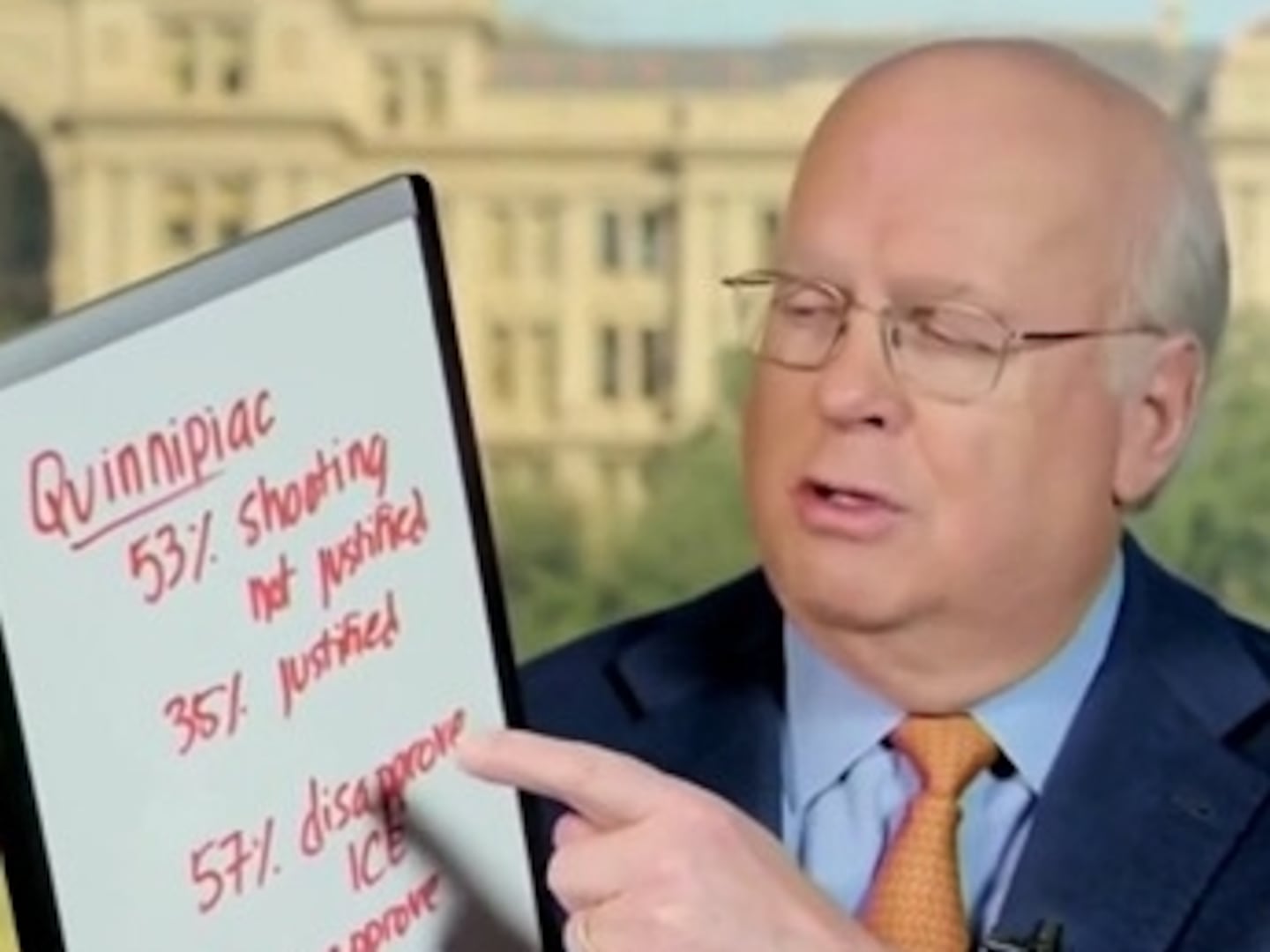

Currently, there are 77 “red notices” for Chinese nationals listed on Interpol's website (though there may be more that have not been made public). Human Rights Watch has suggested that China’s usage of the system is at times “politically motivated,” and that Beijing has targeted “dissidents and others abroad whom China deemed problematic.”

HRW has cited the example of U.S.-based activist Wang Zaigang, who believes that his pro-democracy advocacy has caught the attention of the Chinese government and earned him a “red notice.” According to HRW, the families of Chinese nationals tagged with Interpol’s “red notices” are often subjected to collective punishment, harassment, travel bans, and intimidation.

In February this year, Beijing blasted Interpol’s decision to remove a “red notice” for Dolkun Isa, an exiled Uyghur politician and German national the Chinese Communist Party accuses as one of the leaders of an Uyghur secessionist movement. The Chinese Foreign Ministry has labeled Isa a terrorist and makes frequent requests for European governments to arrest and extradite him, but has never offered any evidence of criminal activity.

There has been a clear pattern of dissidents and high-profile figures mysteriously “vanishing” in China. These include booksellers and publishers who produce literature critical of the Chinese Communist Party, and the recent disappearance of film star Fan Bingbing, who was not seen for months but reappeared this week, praising the Chinese government after “profound thought and reflection.”

Several billionaires also have suffered similar fates, with all of them eventually running newspaper ads or posting on social media to say that they were, in fact, not abducted by the Chinese government. The dragnet has trapped many Party members in the past, too, under the guise of Chinese President Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign.

Despite the lack of clarity about how he might have offended Xi or other top officials, it is widely speculated that they are the ones holding him incommunicado.

Could it be that Meng hasn’t been “loyal enough” to China’s ruling party, having failed to arrange the extraditions of critics who reside abroad?

At the time of this writing, news of Meng’s disappearance has not been reported in China, at least not by state media. But we can expect to hear from him very soon, perhaps with a message stressing that he could have been almost anywhere except in a guarded room in his home country.