For sheer horror and depravity, it’s hard to top the testimony of former gangster Steve Flemmi, speaking from the witness stand at the trial of mobster James “Whitey” Bulger in Boston. On Friday, Flemmi described how he played a role in the murder of his girlfriend Debra Davis. According to Flemmi, Davis, 26 years old at the time, was strangled to death by his partner in crime, Bulger, who was 52. After the life had been squeezed out of her body by Whitey, Flemmi stripped her naked, then yanked out her teeth so the remains could not be identified. He and Bulger than trussed up her body and stuffed it in a bag. They drove to the Neponsit River and, as Bulger sat and watched, Flemmi dug a grave for what remained of his now former girlfriend.

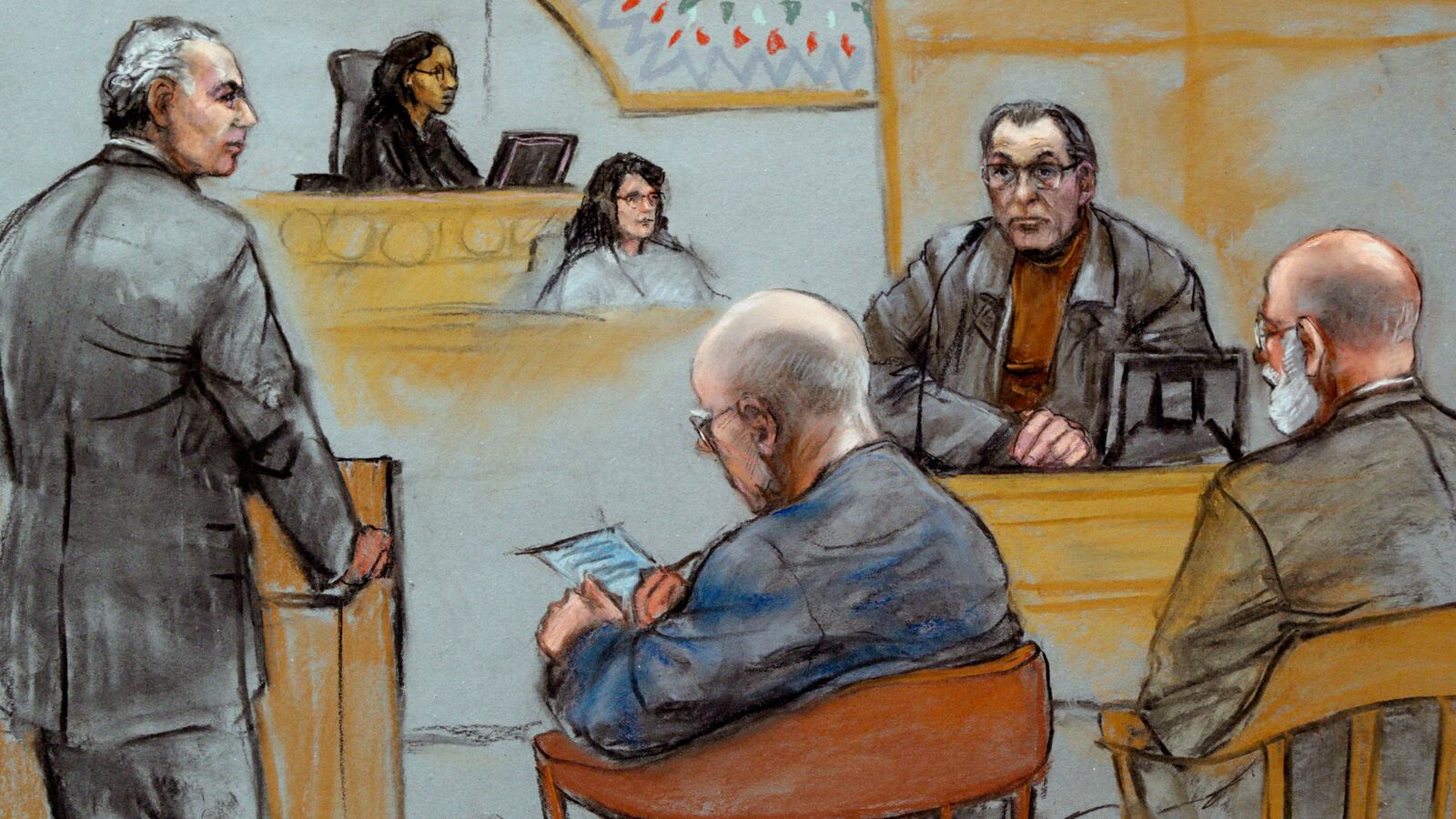

From the stand, Flemmi looked harmless. Ag age 79, he is gray-haired and somewhat doddering. He complained of poor hearing in one ear. Wearing glasses and dressed in a green windbreaker, he described a lifetime of mayhem and murder as a member of the Winter Hill gang, an ultraviolent criminal organization that he and Bulger used to spread terror and make themselves rich in the Boston underworld of the late-1970s and ’80s. Flemmi’s testimony, though filled with stories of brawls, shootings, and body disposals, was mostly dry and dispassionate—until he described the 1981 murder of Debbie Davis. “It’s affected me my whole life,” he claimed. “It will always affect me.”

It was a convincing sentiment, until you stop to consider that three years after the Davis murder—as the jury has been informed throughout the trial up till now—Flemmi was involved in the murder of another woman named Debbie. Also 26 at the time of her death, Deborah Hussey was the daughter of Flemmi’s longtime girlfriend Marion Hussey. While still living with Marion, Flemmi coerced Debbie Hussey at the age of 18 into a sexual relationship (he was 42). When it became apparent that Debbie Hussey was becoming a problem and might reveal the fact that Flemmi was sexually molesting her, Flemmi and Bulger decided she must die.

The method was remarkably similar to the murder of Davis. They lured her to a home in South Boston; Bulger allegedly grabbed her by the neck and strangled her; they buried the body in an unmarked grave.

Throughout the trial, prosecutor Fred Wyshak has elicited the details of these and other murders in gruesome detail. In the case of Flemmi, the details were too much for some on the jury. As the aging gangster described the murder of Davis, one female juror put a hand over her mouth and appeared to weep.

Flemmi’s testimony was indeed shocking. It was also a diversion from an even deeper horror in the Bulger trial, one that Wyshak and the prosecution team have been attempting to bury deeper than the bodies of the two Debbies.

Last week, the trial took a diversionary turn of another kind courtesy of an event outside the courtroom. As an unusually large media contingent arrived at the Moakley Courthouse in South Boston on Thursday morning to hear the testimony of Flemmi—the most important witness in the trial—news spread through the halls that a well-known figure in the case—who until two days earlier was expected to be a witness for the prosecution—had been found dead under mysterious circumstances the previous day.

Stephen “Stippo” Rakes, 55, had attended the trial as a spectator nearly every day up to that point. He was an alleged extortion victim of Bulger, who had engaged in a hostile takeover of a liquor store that Rakes once owned. Rakes had claimed that Bulger and his right-hand man, Kevin Weeks, flashed a gun in front of his infant daughters during the negotiation. Rakes was paid $100,000 for the store, though he claimed it was worth much more.

Earlier in the trial, Kevin Weeks took the stand and testified that Rakes, in fact, had come to Bulger with the offer to sell the store and then tried to shake them down by raising the price. “I don’t like Stippo Rakes,” Weeks said numerous times from the stand.

Some early media reports of Rakes’s untimely demise wrongly noted that he was scheduled to testify at the trial, giving the impression that—in classic gangland fashion—he might have been whacked to guarantee his silence. In fact, he had been removed from the witness list by the prosecution and informed the day before his death that he would not be called. He was reportedly upset that he would not be given the chance to tell his version of being extorted by Bulger for the first time in a public venue.

Rakes’s body was found on a jogging path in Lincoln, Massachusetts, a considerable distance from his home in Quincy. His body was fully clothed, and there were no signs of violence or foul play, though he was found with no cellphone, no wallet, and his car was nowhere nearby. State police have determined the circumstance surrounding his death to be “suspicious,” speculating that he may have died elsewhere and been dumped at that location. An attorney for the Rakes family, Anthony Cardinale, a well-known criminal defense lawyer in Boston, said that he believes Stephen Rakes’s death is not connected to the Bulger case. There will be no official statement until medical authorities are able to determine the cause of death, which may take weeks.

The strange timing of Rakes’s death, as dramatic as it was, was quickly overshadowed by the appearance of Flemmi, a convicted murderer currently residing at Otisville Prison in New York on a life sentence.

Flemmi’s former partner, Bulger, stands accused in a 32-count indictment that includes 19 murders. Flemmi was alongside Bulger for seven of those murders, and has admitted to committing three others. An earlier witness against Bulger, John Martorano, another Winter Hill gang associate, admitted to 22 murders. Most of these killings were done to protect and promote a criminal enterprise that engaged in a smorgasbord of rackets, including illegal gambling, extortion, money laundering, narcotics sales, and more.

How Bulger, Flemmi, and their associates managed to wreak havoc and amass a huge body count over a period of more than 20 years is a horror story as insidious as any of the murder charges in the indictment.

Flemmi, more than any other witness, knows where the bodies are buried. In a long criminal career that began in the late 1950s and continued until his arrest in 1995, Flemmi was privy to levels of corruption in law enforcement the full dimensions of which the prosecution has been vigorously seeking to limit throughout the Bulger trial.

From the stand, Flemmi mentioned the name of H. Paul Rico, a now-deceased FBI agent of great renown in the annals of the bureau. In the early 1960s, Rico seized on a directive by Director J. Edgar Hoover to find and cultivate criminal informants as part of a newly instituted Top Echelon (TE) informant program. Rico was a Runyonesque, tough-talking agent who had a talent for mixing with hoods and mob killers.

From the stand, Flemmi described in some detail how Rico inserted himself into the infamous Boston gang war of the 1960s, resulting in more than 60 gangland deaths in a six-year period. Rico functioned as a gangland puppet master, playing one side against the other, arranging gangland murders, and perhaps taking part in murders himself.

Flemmi described how, when they were trying to find and murder Punchy McLaughlin, a rival gangster, they turned to Rico, head of the FBI’s organized-crime unit. Rico and his partner, Dennis Condon, put McLaughlin under surveillance, determining that he caught the bus every morning at a certain stop. Agents Rico and Condon passed the information on to Flemmi.

“Did Punchy McLaughlin show up at that bus stop?” prosecutor Wyshak asked Flemmi.

“Right on time,” said the witness.

“What did you do?”

“We were waiting for him. I stepped out from the side of the pole and I shot him.”

“How many times?”

“Six times.”

“Did you murder him?”

“Yes.”

As Flemmi spoke, it was as if you could feel the ghost of Paul Rico in the room. Rico was the lawman as gangster, only more rarified. Hoodlums treated him like royalty, hoping he would side with them. In the FBI, he became legendary for his ability to cultivate informants, and he was a central figure in the FBI’s increasing infatuation with its informant program.

Among the first informants signed up by Rico and Condon was Vincent “Jimmy the Bear” Flemmi, Steve Flemmi’s brother. The Bear officially became an informant in 1965, just days after he murdered a low-level Boston hoodlum named Teddy Deegan. At the time, the Deegan murder was still under investigation. This murder, and the Bear’s role in it, would signal the first time, though not the last, that a New England gangster would—in conjunction with corrupt law enforcement officials—manipulate the justice system and use it as a virtual extension of the criminal underworld.

Things worked out so well for the Bear that he persuaded his crime partner Joe “the Animal” Barboza to also go into business with Rico and Condon as an informant.

Barboza had engaged in many criminal acts with the Bear, including playing a role in the murder of Teddy Deegan. Under the tutelage of the FBI and state and federal prosecutors, Barboza soon became a one man wrecking crew, or, as Flemmi described Barboza, “a notorious figure in Boston.”

Rico, Condon and others in the U.S. Department of Justice hoped to use Barboza as a witness against mafia boss Raymond Patriarca, don of the Patriarca family, which controlled all of New England. In order to inoculate Barboza and keep him clean as a witness, they literally allowed him to get away with murder and frame innocent people from the witness stand. To the FBI and U.S. Attorney’s Office in the District of Massachusetts, it was worth it. Barboza helped them make cases against the mafia, which made headlines and catapulted their careers.

Following the Patriarca trial and the Deegan murder trial, Barboza was ushered into the newly conceived Witness Protection Program. He was relocated to Northern California, where, while living under a fake identity provided by the government, he soon murdered a man. When Barboza was put on trial for the murder, the FBI flew agents Rico and Condon to California to testify on his behalf. The prosecutor in California was so startled by FBI agents acting as virtual character witnesses for Barboza that he became concerned he would lose the case. As a result, in midtrial, the prosecutor lowered the charge and allowed Barboza to plead out to a lighter sentence. Eventually, in 1979, Barboza was murdered in San Francisco by a team of hitmen sent from Boston.

In the mid-1970s, Rico and his partner Dennis Condon, in the waning stages of their careers as G-men, passed along their methods—and, more importantly, their sources in the underworld—to special agents John Connolly and John Morris. These two agents—Connolly and Morris—would undertake a relationship with Whitey Bulger that was a historical continuation of all that had come before.

In his testimony, Flemmi claimed that when Bulger first introduced him to special agent Connolly at a coffee shop in Newton. Massachusetts, “I suspected I was being set up. I was suspicious of it, about why he wanted me to meet him.” Flemmi seemed to be suggesting that Bulger was somehow tricking him into becoming an informant for the FBI. This premise works only if you are not aware that Flemmi’s brother had been an informant before him, and that Flemmi himself had been an informant, first opened in 1967 and then closed in 1971, when he was forced to go on the lam following his involvement in the car bombing of Barboza’s lawyer, John Fitzgerald. Despite his implied resistance to establishing an informant relationship with Connolly and Bulger, Flemmi was reopened as a TE in 1975, with Connolly listed as his handler.

Once Bulger and Flemmi were within the FBI stable, their business opportunities seemed to skyrocket. Connolly provided them with all manner of information about criminal investigations being conducted by other law enforcement agencies and about potential informants in their midst. Flemmi described how, thanks to Connolly, they learned that a gangster named Richie Castucci had given information to the FBI on the whereabouts of two key Winter Hill gangsters who were hiding out in New York’s Greenwich Village. Castucci, it turned out, was an FBI informant. Connolly showed that his loyalty was to Winter Hill and not the FBI by ratting out Castucci.

According to Flemmi, the leadership of Winter Hill at the time—himself, Howie Winter, Whitey Bulger, and John Martorano—had a meeting to discuss what to do about Richie Castucci. “Collectively we made a decision,” said Flemmi.

“And what was that decision?” asked Wyshak.

“Kill Richie Castucci.”

They lured Castucci to their headquarters, an office inside Marshall Motors, a garage at 14 Marshall Street in Somerville. Getting him there wasn’t difficult. John Martorano owed Castucci $130,000 in loansharking debt. Johnny told Richie they had his money. When Richie showed up, they told him the money was in an apartment a few doors down that the gang used as a safe house. Richie went with them down to the apartment. When they entered, Martorano shot Castucci in the back of the head. Richie bled all over the place. Bulger and Flemmi cleaned up the blood and brain matter. They zipped up Castucci’s body in a sleeping bag and took it down to the basement, where Howie Winter had brought Castucci’s car. They stuck the body in the trunk of the car and drove over to Revere, where they dumped the remains of Richie Castucci in a deserted location.

Prosecutor Wyshak has not been shy about establishing the corruption of the FBI’s organized crime unit at this trial. Earlier in the proceeding, the unit’s supervisor, John Morris, who was given immunity and avoided prison time, described a culture of corruption that eventually sucked in the entire unit. Wyshak had Flemmi give the names of agents to whom they paid bribe money, a list that included not only Morris and Connolly, but also special agents John Newton, Mike Buckley, Nick Gianturco, and Jack Cloherty. All those agents, except for Morris, deny taking payoffs.

Wyshak is more reticent when it comes to detailing corruption that existed in his own U.S. Attorney’s Office.

A key player in enabling the reign of Bulger and Flemmi was Jeremiah O’Sullivan, head of the federal Organized Crime Strike Force and later U.S. Attorney for the District of Massachusetts. A prosecutor in the Rudy Giuliani mold—hard driving, self-righteous, with an attitude of the ends justifies the means—O’Sullivan was also remarkably successful as a prosecutor, with a high conviction rate.

From the stand, Flemmi briefly mentioned how, in 1978, O’Sullivan’s OC Strike Force was on the verge of handing down dozens of indictments in what became known as “the race fix case.” The Winter Hill gang had been involved in a lucrative scam to fix horse races at tracks around the New England area. O’Sullivan’s case was air tight, and among those on the list to receive indictments were Bulger and Flemmi.

Flemmi described how, when he and Bulger heard about the pending indictments through their sources in law enforcement, they had Connolly arrange a meeting with himself and supervisor Morris at Morris’s home in Concord. Bulger and Flemmi brought a bottle of wine for Morris as a gift. Morris cooked dinner for the group. At the dinner, Bulger and Flemmi suggested that Morris go to Jerry O’Sullivan and try to get them removed from the indictment. Morris said he’d see what he could do.

Within days, Morris and Connolly arranged a meeting with the man who was the top organized crime investigator in the region and requested that he drop Bulger and Flemmi from his. Their value as informants against the mafia precluded their being arrested as racketeers.

O’Sullivan acquiesced, beginning a new phase in which the U.S. Department of Justice now had a vested interest in protecting Bulger and Flemmi, who would go on to kill many more people—including the two Debbies—before Whitey went on the run in 1995.

Throughout the trial so far, whenever questioning by the defense lawyers strays into areas pertaining to Boston’s historical narrative of corruption in the justice system, or, more specifically, the role of the Department of Justice beyond the FBI, the prosecutors usually object. “Your honor,” they ask, “what relevance does this have to the case against James Bulger?” Invariably, Judge Denise Casper sustains the objection.

Flemmi is back on the stand today; his testimony will likely further shock and disgust jurors and observers. But beyond the shock value, Flemmi is a man with a unique perspective on decades’ worth of corruption and nefarious acts at virtually every level of law enforcement in the region’s criminal-justice system. The degree to which that knowledge is brought before the public may depend mostly on the defense lawyers, who begin their cross-examination after the government is finished leading their star witness through a diversionary litany of atrocities.