For most job applicants, the question “Have you ever been known by any other name?” is not a stumbling block.

If you have a maiden name—or if you simply hated your first name and changed it from Jacqueline to Jessica—it’s unlikely that disclosing a previous alias on an application or a background check authorization form would adversely affect your chances of employment.

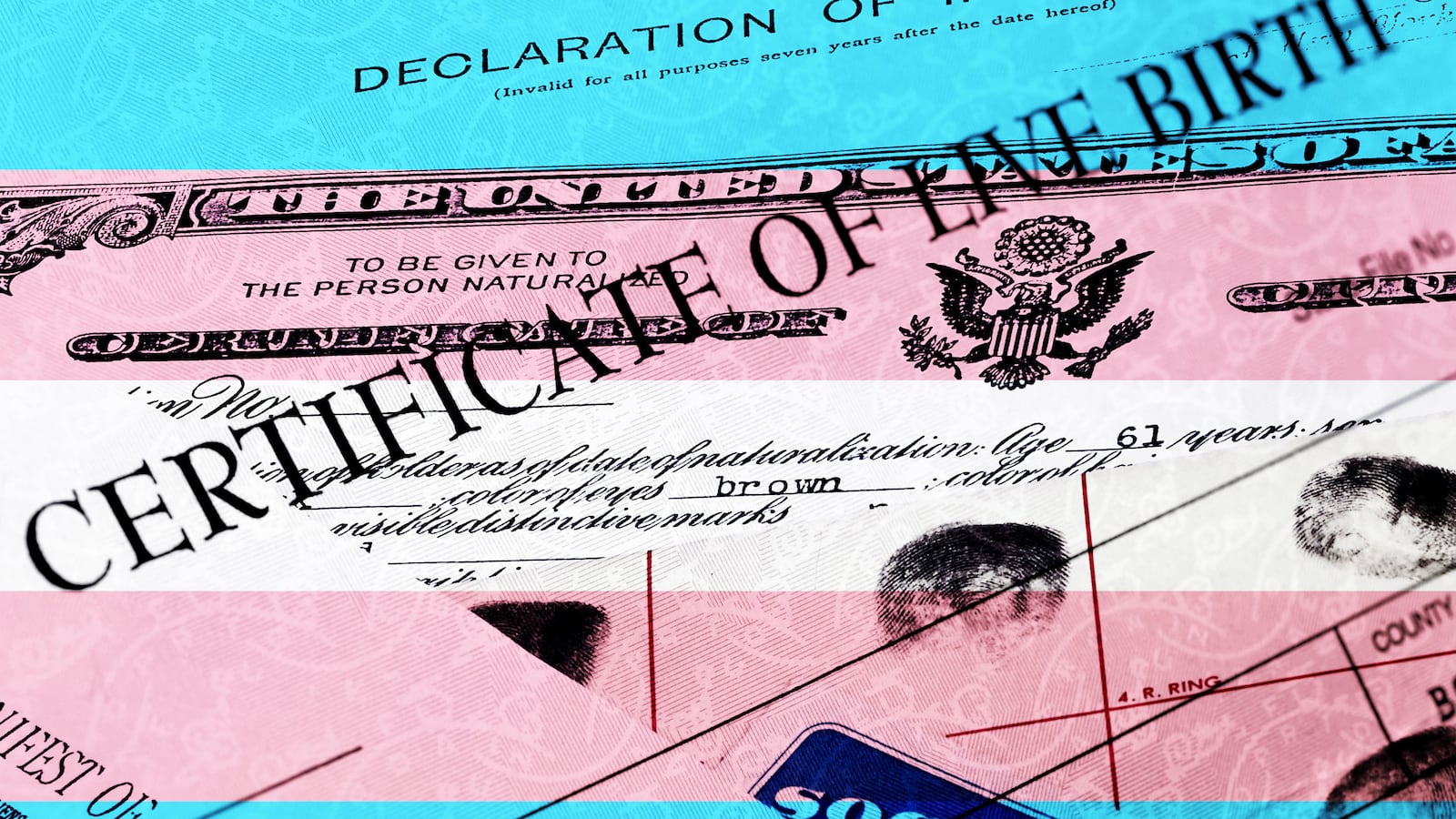

But for transgender applicants, that question can be a perilous catch-22: Unless your pre-transition name was gender-neutral, answering it honestly will out you. But leaving it blank could cause problems, too.

“If you say that no prior names were used when that’s actually not the case, that could leave you open to the charge of lying on the application, which could give your employer reason to fire you,” Jillian Weiss, the executive director of the Transgender Legal Defense and Education Fund, told The Daily Beast.

Transgender people experience poverty and unemployment at astronomical rates compared to the general population. Among the nearly 30,000 respondents to The National Center for Transgender Equality’s 2015 U.S. Trans Survey—which was released last month—nearly one third reported living in poverty; 15 percent reported being unemployed; and 27 percent said they had been fired, denied a promotion, or not hired for a job based on their gender identity in the previous year. (For comparison, the current unemployment rate in the U.S. is less than 5 percent and the poverty rate is 13.5 percent.)

It’s clear that acquiring—and holding onto—jobs is one of the most pressing problems faced by the already-imperiled transgender community. But between name changes, background checks, and social security records (PDF), it’s almost impossible to get through the job application process without revealing your transgender status and opening yourself up to discrimination.

“It is very difficult in this day and age for a person to remain ‘stealth,’” the Transgender Law Center notes in a fact sheet on employment rights. “This is because employers may have access to databases tied to a person’s social security number, which may contain information about previous name and gender information.”

In an ideal world, of course, being transgender would be about as relevant to the job application process as having brown eyes. But in the current environment, accepting the unfortunate inevitability—or at least, the likelihood—of being outed may be an important first step depending on one’s individual situation.

Ashley Brundage, a transgender woman who is now an Inclusion Consultant for PNC Bank, interviewed at over 40 companies before accepting her current position. Over that time, she says, she learned how and when it made sense for her to self-identify as transgender during interviews. At first, she tried not disclosing at all. It didn’t work. So she changed her strategy.

“During later interviews, I began to self-identify [as transgender], which led to greater conversation around diversity and inclusion but no job offers,” she told The Daily Beast. “During my final interviews, I self-identified but also connected my desire to work at a particular company with the business case for diversity and inclusion.”

There is a wealth of research to suggest that LGBT-supportive workplaces reap tangible rewards like higher job satisfaction and increased competitiveness in talent recruitment. But this means that companies that want the benefits of transgender talent need to be sensitive to the obstacles they face during the application and hiring process.

Susan Loynd, director of HR for Washington County Mental Health Services in Montpelier, Vermont, and an expert on the Society for Human Resource Management’s Diversity and Inclusion panel, told The Daily Beast that human resources has a crucial role to play in protecting transgender applicants from unnecessary outing.

“We’ve had people whose name and alias are different genders,” she said. “We don’t show those records to our hiring managers—we have that all here in HR.”

If those internal practices are reinforced by an LGBT-friendly public image, Loynd says, then transgender applicants may be less nervous about applying.

“My hope is that if we present ourselves in our community, at job fairs, in our ads, on our website, and on our Facebook page as a welcoming community, then we can maybe take folks’ anxiety down at least a couple of notches so that they have the self-confidence and the courage to pick up the phone and call us,” she told The Daily Beast.

But not every company wears LGBT-friendliness on its sleeve, which leaves many transgender applicants in search of discreet ways to handle their application process.

For those who are currently navigating the minefield of a job hunt, there is no “one-size fits all” approach, Weiss says. Different levels of background check turn up different information. Some transgender people have changed the name on their educational degrees; others haven’t. Some transgender people have an employment history that predates gender transition; others don’t.

Without offering legal advice, Weiss told The Daily Beast that leaving the “previous name” question blank is “an option” but an employer might still claim that qualifies as an omission of information.

“It can be a difficult choice,” she said, especially because hiring discrimination after revealing one’s transgender status is difficult to prove.

Another option that Weiss described in a 2011 blog post entitled “To Name or Not to Name?” is to “submit a letter separately to the HR department that indicates the fact of transition and requests that the information be kept confidential within the HR department as a matter of medical privacy.”

For her part, Brundage says that even if transgender applicants choose to use a first initial or a preferred name on a resumé as a confidence boost early in the process, they will still have to answer that catch-22 question at some point.

“Eventually, naming will need to be fully addressed by the applicant,” she said.