On August 6, 1945, President Harry S. Truman faced the task of telling the American public, the press, and the world, that America’s war against fascism had culminated in exploding a new weapon of extraordinary destructive power over a Japanese city.

It was vital that this event be understood as a triumph of military power consistent with American decency and concern for life. Everyone involved in preparing the presidential statement over the preceding weeks—including Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson and Gen. Leslie Groves, director of the Manhattan Project—knew that the stakes were high, for this marked the revealing of both the atomic bomb and the official narrative of Hiroshima.

When this shocking news emerged that morning nearly 75 years ago, President Truman was at sea, a thousand miles away, returning from the Potsdam conference, so the announcement took the form of a press release, a little more than a thousand words long. Shortly before eleven o’clock, an officer from the War Department arrived at the White House bearing bundles of publicity releases. Assistant Press Secretary Eben Ayers began reading the president’s announcement to about a dozen members of the Washington press corps.

The statement was so momentous, and the atmosphere so casual, the reporters had trouble grasping it. “The thing didn’t penetrate with most of them,” Ayers later recalled. At least one reporter who rushed to call his editor found a disbeliever at the other end of the line.

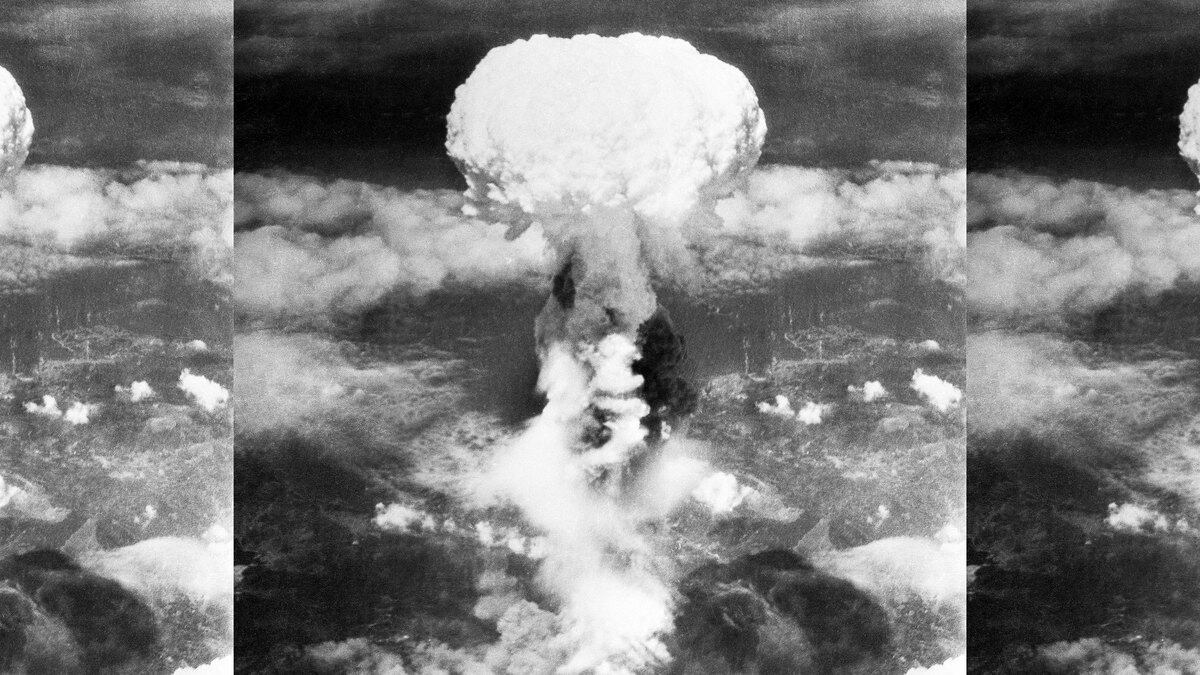

And no wonder. The first sentence set the tone: “Sixteen hours ago an American airplane dropped one bomb on Hiroshima, an important Japanese Army base. That bomb had more power than 20,000 tons of TNT… The Japanese began the war from the air at Pearl Harbor. They have been repaid many fold… It is an atomic bomb. It is a harnessing of the basic power of the universe.”

Truman’s four-page statement had been crafted with considerable care over many weeks, although the target city had been left blank. From its very first words, however, the official narrative was built on a lie: Hiroshima was not an “army base” but a city of 350,000. It did contain one important military headquarters, but the bomb had been aimed at the very center of a city—and far from its industrial area. This was a continuation of the American policy of bombing civilian populations in Japan to undermine the morale of the enemy.

It also aimed to take advantage of what those who chose the target called the “focusing effect” provided by the hills which surrounded the city on three sides. This would allow the blast to bounce back on the city, destroying more of it, and its citizens. Perhaps 10,000 military personnel lost their lives in the bomb but the vast majority of the 125,000 dead in Hiroshima would be women and children. Also: at least a dozen American POWs. (When Nagasaki was A-bombed three days later, it was officially described as a “naval base” yet less than 200 of the 90,000 dead were military personnel.)

There was something else quite vital missing in Truman’s announcement (and his radio/newsreel address three days later): Because the president failed to mention radiation effects, which officials knew were horrendous, the imagery of just a bigger bomb would prevail in the press. Truman described the new weapon as “revolutionary” but only in regard to the destruction it could cause, failing to mention its most lethal new feature: radiation.

At the same time, no one but top American officials and generals knew that the Soviet Union was just hours from declaring war on Japan. “Fini Japs” when that occurred, even without the bomb, Truman had written two weeks earlier in his diary after meeting Stalin.

Many Americans first heard the news about the new bomb and the bombing from the radio, which broadcast the text of Truman’s statement shortly after its release. The afternoon papers quickly arrived with banner headlines: “Atom Bomb, World’s Greatest, Hits Japs!” and “Japan City Blasted by Atomic Bomb.” The Pentagon had released no pictures, so most of the newspapers relied on maps of Japan with Hiroshima circled.

By that evening, radio commentators were weighing in with observations that often transcended Truman's announcement, suggesting that the public imagination was outrunning the official story. Contrasting emotions of gratification and anxiety had already emerged. Famed announcer H.V. Kaltenhorn warned, “We must assume that with the passage of only a little time, an improved form of the new weapon we use today can be turned against us.”

It wasn't until the following morning, August 7, that the government's full press offensive appeared, with the first detailed account of the making of the atomic bomb, and the Hiroshima mission. Nearly every U.S. newspaper carried all or parts of 14 separate press releases distributed by the Pentagon several hours after the president's announcement. They carried headlines such as: “Atom Bombs Made in 3 Hidden Cities” and “New Age Ushered.”

Many of them were written by one man: William L. Laurence, a Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter for The New York Times, secretly embedded with the top-secret atomic project. (He was about to become the only newsman allowed to accompany the mission to Nagasaki with the second bomb, and would be the nation's chief pro-bomb propagandist for weeks to follow.) General Groves would later reflect, with satisfaction, that “most newspapers published our releases in their entirety. This is one of the few times since government releases have become so common that this has been done.” Laurence would earn the nickname, “Atomic Bill.”

The Truman announcement of the atomic bombing on August 6, 1945, and the flood of material from the War Department, firmly established the Hiroshima narrative. It would not take long, however, for breaks in the official story to appear.

General Leslie Groves and “Atomic Bill” Laurence of the New York Times

Photo courtesy of the Patricia Cox Owen Collection.One of the few early stories that did not come directly from the military was a wire service report filed by a journalist traveling with the president on the Atlantic. Approved by military censors, it depicted Truman, his voice “tense with excitement,” personally informing his shipmates about the atomic attack. “The experiment,” he announced, “has been an overwhelming success.”

Missing from this account was Truman's exultant remark when the news of the bombing first reached the ship: “This is the greatest thing in history!”

On August 7, military officials confirmed that Hiroshima had been devastated: at least 60% of the city wiped off the map. They offered no casualty estimates, emphasizing instead that the obliterated area housed major industrial and military targets. The Air Force provided the newspapers with an aerial photograph of Hiroshima. Significant targets were identified by name. For anyone paying close attention there was something troubling about this picture, however. Of the 30 targets, only four were specifically military in nature. "Industrial" sites consisted of three textile mills. Indeed, a U.S. survey of the damage, not released to the press, found that residential areas bore the brunt of the bomb, with less than 10% of the city's manufacturing, transportation, and storage facilities damaged.

On Guam, weaponeer William S. Parsons and B-29 pilot Paul Tibbets calmly answered reporters' questions, limiting their remarks to what they had observed after the bomb exploded. Asked how he felt about the people down below at the time of detonation, Parsons said that he experienced only relief that the bomb had worked and might be "worth so much in terms of shortening the war." (Almost 40 years later, Tibbets would tell me he lost no sleep over his role in the event. In fact, he added, his renown helped attract women to him.)Almost without exception newspaper editorials endorsed the use of the bomb against Japan. Many of them sounded the theme of revenge first raised in the Truman announcement. Most of them emphasized that using the bomb was merely the logical culmination of war. "However much we deplore the necessity," the Washington Post observed, "a struggle to the death commits all combatants to inflicting a maximum amount of destruction on the enemy within the shortest span of time." The Post added that it was "unreservedly glad that science put this new weapon at our disposal before the end of the war."Referring to American leaders, the Chicago Tribune commented: "Being merciless, they were merciful." A drawing in the same newspaper pictured a dove of peace flying over Japan, an atomic bomb in its beak.

Two days later, coverage of the Nagasaki attack drew far less, but equally exultant, reactions. By then, the Russians had entered the war and Japan, in reaction to that and to the bomb, had put out serious peace offers.

The Truman announcement of the atomic bombing on August 6, 1945, and the flood of material from the War Department, firmly established the Hiroshima narrative—that the use of the new bomb had been a military necessity with no other options to end the war and, thereby, countless American lives saved—which still dominates media coverage and public opinion, even as it remains hotly debated (if largely out of view, except at major anniversaries) by historians.

To maintain that narrative, in the weeks and months that followed the atomic attacks, and Japan's surrender, official suppression of the full story ruled. Officials would downplay the number of civilian casualties in the two cities and dispute as “propaganda” reports from Japan of extreme suffering caused by a unique human effect—“radiation disease.” (General Groves would even tell Congress that he had heard that this was a “rather pleasant way to die.”) Radioactive fallout from the first test of the bomb in New Mexico back in July had drifted to earth across the U.S. but this was kept from the press and public.

When the first journalist from outside Japan, Wilfred Burchett from Australia, reached Hiroshima four weeks after the bombing, his report had to navigate the new U.S. censorship office established in Tokyo, and was finally published by a newspaper in London. A week later, the first U.S. reporter to arrive in Nagasaki, George Weller of the Chicago Daily News, began filing graphic reports on the human toll there. His stories would be quashed by that censorship office and would not appear for another sixty years. Other U.S. reporters would only be allowed to visit the two cities accompanied by official minders and for brief periods and then endured official censors, even though the U.S. was no longer at war.

That occupation office, under General Douglas MacArthur, also prohibited reporting and photography by Japanese journalists. The U.S. military seized all of the historic newsreel footage shot by the Japanese in the days after the bombings. It would disappear forever. It would then order the same Japanese crew to shoot more footage and create a documentary film—which the U.S. would label top secret and bury in archives for the next quarter century.

All of the even more graphic color footage shot in the atomic cities by an elite American military team would likewise be hidden from the public for over three decades.

Also that autumn, MGM launched the first major movie drama on the bomb, The Beginning or the End. The film, which is the subject of my new book, was inspired by the desperate pleas by atomic scientists urging Hollywood to warn the world of the dangers of building more powerful weapons and the certain arms race to follow.

Over the following months, however, after granting script approval to both General Groves and President Truman, the story would be heavily revised, and falsehoods added, to fully endorse the dropping of the bomb over Japan and the U.S. determination to remain on the nuclear path.

At the same time, Truman and his allies plotted to blunt the impact of John Hersey's epochal "Hiroshima" article in The New Yorker, convincing Stimson to write a cover story for Harper's stoutly defending the decision to drop the bomb. This succeeded, and the Hiroshima narrative, put forward seventy-five years ago this week, was virtually set in stone for decades…even, one might say, to this day.

Why does this matter now? Few may know that the U.S. maintains its official “first-use” policy initiated in August 1945. Any president—and, most worryingly, the present one—has full authority to order a pre-emptive first-strike not in retaliation for a nuclear launch in our direction but during any conventional war or even in response to verbal threats from an enemy.

How the Hiroshima narrative has been handed down to generations of Americans — and overwhelmingly endorsed by officials and the media, even if many historians disagree — matters greatly. Over and over, top policymakers and commentators say, “We must never use nuclear weapons,” yet they endorse the two times the weapons have been used against major cities in a first strike. To make any exceptions, even in the distant past, means exceptions can be made in the future. The line against using nuclear weapons has been drawn… in shifting sand.

Greg Mitchell's latest book is The Beginning or the End: How Hollywood—and America—Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb. He recently finished directing the first film on the suppression of the Japanese and American footage shot in 1945-1946.