In 1863, Scott Harker and his family resettled from the Creek Territory, in what is now Oklahoma, to just outside the brand new city of Denver. Under president-elect Abraham Lincoln’s new Homestead Act, Harker filed a claim for 160 acres at their new home. But he died the next year, leaving his wife, Adeline, alone with their three children. Had Harker passed even a few years earlier, his family’s journey west might have ended there, because in that era, women rarely saw opportunities to work, much less acquire land, on their own.

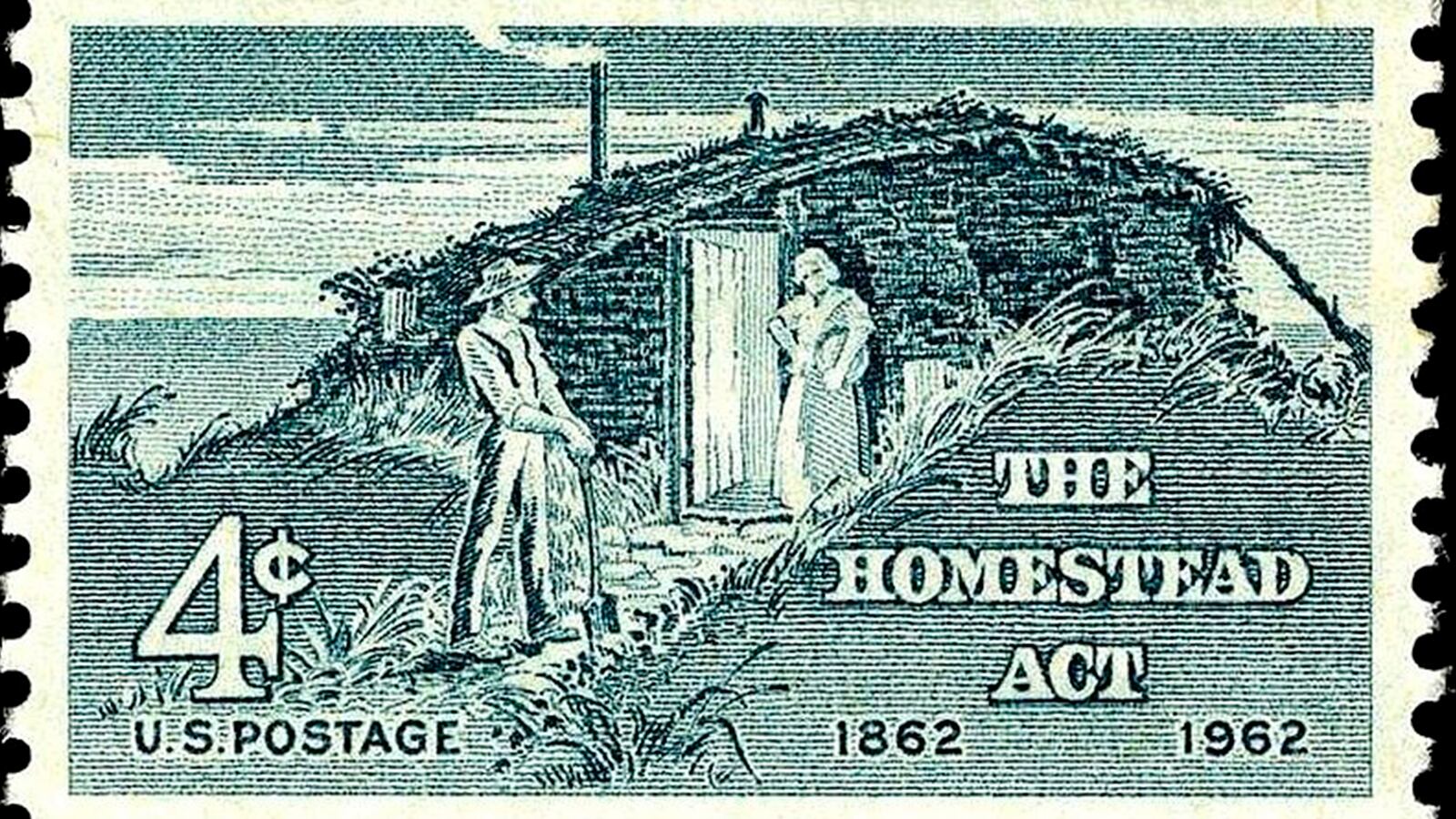

But the Homestead Act of 1862 made way for westward expansion toward the Great Plains, which encompassed Kansas, Nebraska, Oklahoma, and the Dakotas. It also made land ownership available to more than a privileged few. When Lincoln signed his legislation to law, he said, “[T]he wild lands of the country should be distributed so that every man should have the means and opportunity of benefiting his condition.” This was fortunate for the now-widowed Adeline, who had three children to raise. In 1866, she bought 80 acres for $100 in cash in Colorado—a steal compared to what land cost the century before.

Under the Land Ordinance of 1785, Americans had to buy a minimum of 640 acres at $1 per acre to stake a claim. The U.S. government later slashed that prerequisite in half to 320 acres, then allowed for payment in four installments. Still, most Americans couldn’t afford the investment. Therefore, they couldn’t participate in their own country’s democracy. Historically, prospective voters needed to own land, like 50 acres in Delaware by 1763, according to the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. It was assumed that if you owned land, you must be invested in the country’s future. Unfortunately, that logic dictated that a good number of white men and most African Americans, Native Americans, and women didn't hold a political voice.

A More Equal Union

The Homestead Act would upend that status quo—and it was met with plenty of resistance. Northern factories didn’t want their cheap labor force to abandon them, while Southern plantations were weary of boosting representation for the abolition of slavery out west. The House of Representatives tried three times—in 1852, 1854, and 1859—to answer to growing demand for homestead legislation, only to find it rejected by the Senate. In 1860, president James Buchanan vetoed a bill that would have provided federal land grants to Western settlers.

Previously, the U.S. government offered homestead claims to a select few, such as with the Armed Occupation Law of 1842, which awarded land to those willing to help fight the Indian resurgence in Florida. But the Homestead Act of 1862 significantly broadened that criteria. Applicants only needed to either be 21 years old or the head of a household. They paid a small registration fee and, if they coughed up $1.25 per acre, they could own that land outright after six months. From there, all they had to do was live on the land continuously while cultivating and improving upon it for five years.

Take Adeline, for example: In 1870, two months after she resettled in Colorado’s Florissant Valley, 35 miles west of Colorado Springs, she remarried and had a fourth child with Elliott Hornbeck. Five years later, Hornbek disappeared. “[He] abandoned me,” Adeline wrote on one homestead application. Meanwhile, her proof of homestead was astounding. By spring 1878, Adeline had the first two-story house in the area. Her log house had four bedrooms, three of them on the second floor. Her ranch boasted a chicken coop and stables for nine horses. “My said husband did not pay for any improvements nor any portion thereof,” she wrote.

Adeline’s success story matched Lincoln’s ambitions for the Homestead Act—to, at its best, make land ownership a more democratic process. Unmarried, widowed, and divorced women all qualified. As part of the exoduster movement, the mass exodus to escape Jim Crow oppression, more than 25,000 African Americans moved from the South to Kansas in the 1870s and 1880s. In the Homestead Act’s century-long duration, around 270 million acres—that’s one-tenth of the United States back then—would be claimed and settled.

Nothing Is Perfect

To be fair, that statistic doesn’t distinguish land owned by good, honest people from that owned by speculators: those who found loopholes within the Homestead Act to score 10,000- to 600,000-acre blocks at a time—about 100 million acres total, or ten times more than actual homesteaders. Although the law stipulated that claimants must live on their land continuously, speculators sneakily wheeled portable cabins and hired civilians as “eyewitnesses” to their residency. In this way, the Homestead Act called attention to how the real-estate marketplace still lacked ethics and structure by way of licensing laws. Fortunately, after a Public Land Commission by Congress in 1879 failed to combat land fraud, citizens themselves took action. In 1908, Edward Sanderson Judd gathered 120 people in Chicago to form the National Association of Real Estate Exchangers—today, the National Association of REALTORS® (NAR). The first rule in the organization's founding code of ethics, published in 1913, plainly explained its intentions: “Be absolutely honest, truthful, faithful and efficient.”

For its imperfections, the Homestead Act had a profound effect on America, which poet and essayist Walt Whitman explained in 1856: “A man is not a whole and complete man until he owns a house and the ground it stands on.” Much later, President John F. Kennedy called the Homestead Act “the single greatest stimulus to national development ever enacted.”

Surely, both men would have been inspired by Adeline. When she filed her last proof of homestead in 1885, she stressed that she was, in fact, the head of the household—chances are, she knew that a female property owner was still an anomaly. She lived on her sprawling Florissant ranch for 27 years before she died in 1905. She was known around town for working at the general store, supporting herself financially as her property value grew fivefold. She remarried twice after her first husband Scott Harker's death. But Adeline Warfield Harker Hornek Sticksel (her name by her passing) never moved in with her new spouses, instead inviting them to move in with her. Her claim in these “wild lands of the country,” as Lincoln once said, was absolutely hers.