There has been no shortage of media attention paid to the role of money in the current presidential contest. Super PACs, bundlers, 527s, and mega-donors have attracted abundant notice. But there has been surprisingly little focus on perhaps the most secretive and influential financial force in politics today: the wide-open coffers of the Internet.

With millions of online campaign donations ricocheting through cyberspace, one might think the Federal Election Commission would have erected serious walls to guard federal elections from foreign or fraudulent Internet contributions. But that’s far from true. In fact, campaigns are largely expected to police these matters themselves.

There’s certainly ample historical reason to worry about foreign donations: in the 1990s, for instance, there were allegations that Chinese officials had funneled money into U.S. campaigns.

ADVERTISEMENT

The solicitation of campaign donations from foreign nationals is prohibited by the Federal Election Campaign Act. But that law, passed in the 1970s, did not anticipate the Internet, or the creative uses that can be made of such social media as Facebook.

Campaigns that aggressively raise money online are soliciting donations from people around the world—whether they intend to or not. People repost campaign solicitations on blogs that send them sprawling around the globe like digital kudzu. For example, an Obama campaign official posting ended up on Arabic Facebook, complete with a hyperlink to a donation page. In another instance, someone posted videos on Latin American websites featuring Sen. Marco Rubio, and included embedded advertisements asking for campaign donations.

In addition, people around the world are being asked for donations by the campaigns themselves, simply because they signed up for information on campaign websites. The problem: candidate webpages don’t ask visitors from foreign IP addresses to enter a military ID or passport number. Instead, the websites use auto-responder email systems that simply gather up email addresses and automatically spit out solicitations.

The FEC, meanwhile, has taken the position that this sort of passive internet solicitation is not illegal, because the campaigns, presumably, are not intentionally targeting foreign nationals with their online money pleas.

Further complicating the issue are websites like Obama.com—which is owned not by the Obama campaign but by Robert Roche, an American businessman and Obama fundraiser who lives in Shanghai. Roche’s China-based media company, Acorn International, runs infomercials on Chinese state television. Obama.com redirects to a specific donation page on BarackObama.com, the official campaign website. Unlike BarackObama.com, Obama.com’s traffic is 68 percent foreign, according to markosweb.com, a traffic-analysis website. According to France-based web analytics site Mustat.com, Obama.com receives over 2,000 visitors every day.

The name Robert W. Roche appears 11 times in the White House visitors log during the Obama administration. Roche also sits on the Obama administration’s Advisory Committee for Trade Policy and Negotiations, and is a co-chair of Technology for Obama, a fundraising effort. (In an email exchange, Roche declined to discuss his website, or his support for the Obama reelection effort, referring the inquiries to the Obama campaign team. The Obama campaign, in turn, says it has no control over Roche’s website; it also says only 2 percent of the donations associated with Obama.com come from overseas.)

But it isn’t just foreign donations that are a concern. So are fraudulent donations. In the age of digital contributions, fraudsters can deploy so-called robo-donations, computer programs that use false names to spew hundreds of donations a day in small increments, in order to evade reporting requirements. According to an October 2008 Washington Post article, Mary Biskup of Missouri appeared to give more than $170,000 in small donations to the 2008 Obama campaign. Yet Biskup said she never gave any money to the campaign. Some other contributor gave the donations using her name, without her knowledge. (The Obama campaign explained to the Post that it caught the donations and returned them.)

This makes it all the more surprising that the Obama campaign does not use a standard security tool, the card verification value (CVV) system—the three- or four-digit number often imprinted on the back of a credit card, whose purpose is to verify that the person executing the purchase (or, in this case, donation) physically possesses the card. The Romney campaign, by contrast, does use the CVV—as has almost every other candidate who has run for president in recent years, from Hillary Clinton in 2008 to Ron Paul this year. (The Obama campaign says it doesn’t use the CVV because it can be an inhibiting factor for some small donors.) Interestingly, the Obama campaign’s online store requires the CVV to purchase items like hats or hoodies (the campaign points out that its merchandise vendor requires the tool).

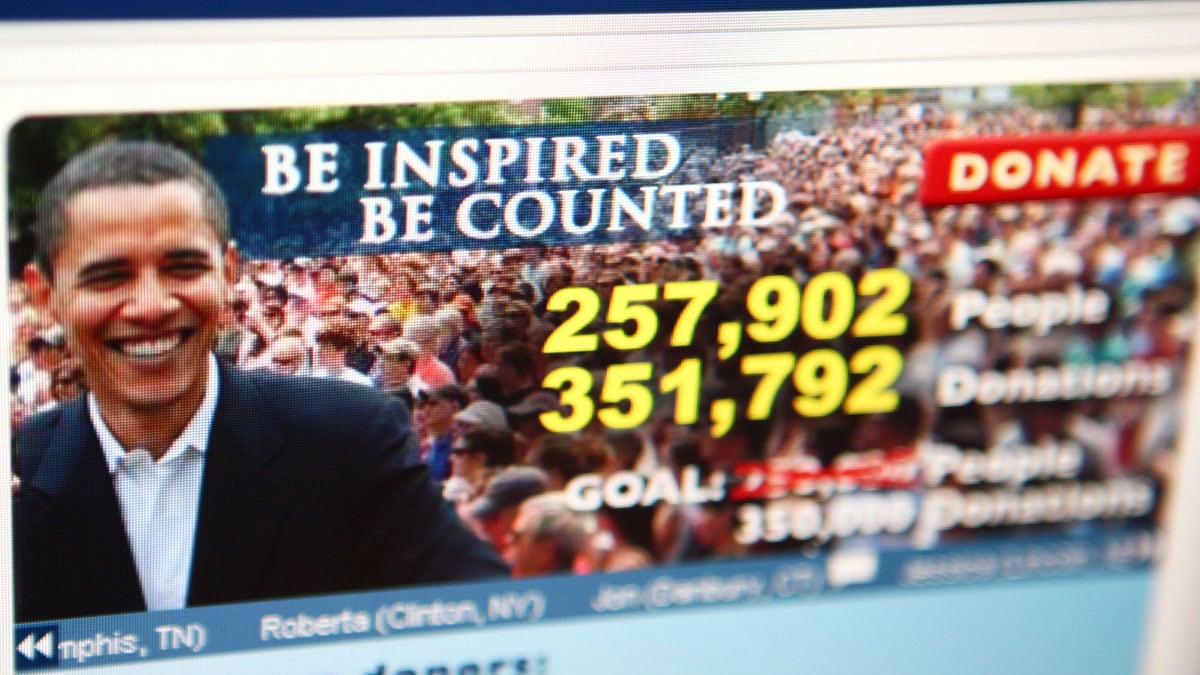

We also focused on the Obama campaign because it is far more successful than Romney when it comes to small donors—which the Internet greatly helps to facilitate. In September the Obama campaign brought in its biggest fundraising haul—$181 million. Nearly all of that amount (98 percent) came from small donations, through 1.8 million transactions.

The Obama campaign says that it is rigorous in its self-regulation effort. “We take great care to make sure that every one of our more than three million donors are eligible to donate and that our fundraising efforts fully comply with all U.S. laws and regulations,” says campaign spokesman Adam Fetcher. Campaign officials say they use multiple security tools to screen all online credit-card contributions, and then review, by hand, those donations that are flagged by their automated system. Potentially improper donations, such as those originating from foreign Internet addresses, are returned to any donors who cannot provide a copy of their current U.S. passport photo pages, the campaign says.

But the weakness of the current system isn’t particular to any campaign. It’s a broad reliance on self-policing combined with a lack of transparency. Foreign or fraudulent donations might be less of a concern if it were possible for outsiders—the press, the public, good government watchdog groups, or the Federal Election Commission—to independently determine whether they were taking place. But it isn’t. Candidates need only publicly report campaign contributions over $200. For donations between $50 and $200 (the average donation in Obama’s huge September haul was $53), candidates are simply required to make an effort to obtain accurate identifying information—information they aren’t required to report. And for donations under $50, regulations don’t even require campaigns to keep a record of identifying information.

The FEC, to be sure, does occasionally conduct investigations into foreign or fraudulent donations. But the majority of these investigations only result in civil fines or closure without action. There is much more that could be done to remedy this situation. First, campaigns should be required to disclose identifying information on all their donors, not just those who give over $200. Second, campaigns should be required to ask for the CVV number when accepting donations. Finally, campaigns should be required to ask people signing up for campaign information whether they are able to legally donate. There is simply no reason non-Americans should be solicited for donations via email.

Until such measures are enacted, however, the integrity of our campaign-donation system will remain mostly in the hands of political consultants and campaign managers. Is that wise?

For more on the subject, see this new report from Peter Schweizer’s Government Accountability Institute.