Where the Alabama mainland meets the Gulf of Mexico, a narrow waterway—just a few hundred feet in most places—separates a picturesque coast of white sands and beach towns from the rest of the state.

Those 30-some miles of shorefront are a point of pride and an economic lifeline for Alabama; each year, millions of vehicles cross over the Intracoastal Waterway to enjoy it.

For decades, there have been two options to do so: the Alabama State Route 59 bridge, or the Beach Express Bridge, a toll route operated by a private company.

But with infrastructure aging and traffic growing—particularly during the busy summer season—public officials and stakeholders have long agreed that major improvements are required to ensure the coast’s visitors and residents can reach it smoothly.

Around the country, similar problems are routinely tackled without much controversy or incident. Roads are widened, bridges are built, constituents are satisfied.

But in this corner of Alabama, tackling this problem has proved anything but routine.

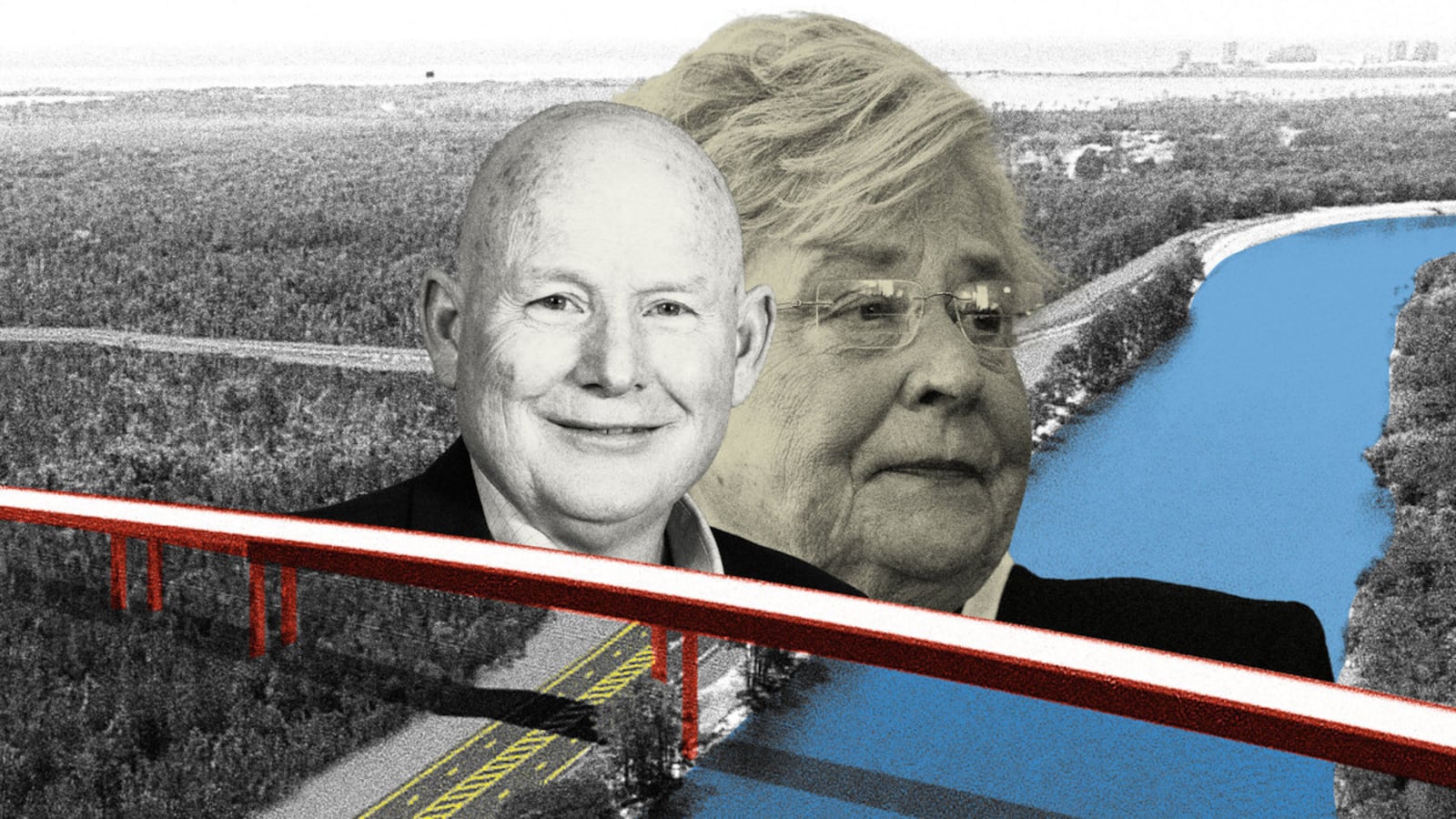

Over the course of years, this small stretch of water has become the source of a political, legal, and logistical black hole that has sucked in everyone from the beach town mayors to incumbent Gov. Kay Ivey, metastasizing into a debacle that many locals worry will do them all long-term harm—and embarrass the entire state in the process.

If the director of the Alabama Department of Transportation, John Cooper, has his way, there will one day be a monument to that black hole: a $120 million bridge across the Intracoastal Waterway that everyone from local activists to a federal judge has dubbed a “boondoggle” to “nowhere.”

In 2005, the so-called “Bridge to Nowhere”—connecting Ketchikan, Alaska, to Gravina Island and its 50 residents for a proposed cost of $400 million—became a flashpoint in the war on government waste. The backlash to the project helped spur Congress to eventually ban earmarks five years later.

Almost two decades later, this state government project is having a similar, if not more divisive, effect on Alabama residents.

In 2020, Alabama’s Department of Transportation appropriated $1.6 billion—a mix of state, federal, and local funds—so the cost of the bridge would hardly be a drop in the bucket for Alabama, even when legal and construction issues inevitably drive up the cost.

Across Alabama, Cooper has long been notorious for his muscular wielding of power and his legendary holding of grudges. A popular quip—“it’s Mr. Cooper’s way or no highway”—is usually delivered by insiders with a laugh, groan, or both. (In June, he was arrested for allegedly threatening to shoot and “whoop” his neighbor over a property-related disagreement.)

Even by his standards, Cooper’s stubborn push to build an expensive new bridge to the Gulf Coast has confounded his sympathizers and created a legion of enemies who are determined to kill the project or pressure Ivey to give him the boot—whichever comes first.

The state’s lieutenant governor, Will Ainsworth, has gone a step further: On Aug. 12, he said if he were in charge, Cooper would be “fired on day one.” He cited a number of disappointments, including his handling of the Intracoastal Waterway bridge.

For opponents of the project, it’s hard to decide what aspect of the years-long process most infuriates them. For one, the Alabama Department of Transportation, or ALDOT, proposed building the new bridge a mile from the toll bridge. There’s also the fact that the proposed span would merely feed into the same two clogged roads that the existing two bridges already do. It would not create any new through-ways to the beach—hence the “bridge to nowhere” moniker.

Local skepticism hardened to outrage when it came out that ALDOT never so much as commissioned a traffic study to assess what all those dollars needed to build the bridge would actually do.

Cooper admitted as much in state court, where his department was defending a lawsuit from the toll bridge operator. That’s the other aspect of the saga that rankles many: After Cooper declined the Baldwin County Bridge Company’s offer to expand their bridge, make it free to locals, and ultimately fund construction of a new bridge, it alleged the state was trying to run them out of business.

In May, Montgomery-based state circuit Judge Jimmy Pool agreed. In a remarkably blunt opinion, Pool ordered the state to immediately halt construction of the bridge, calling it a pointless “boondoggle” and “a complete waste of over $120 million in taxpayer funds to carry out the personal vendetta” of Cooper.

ALDOT appealed the decision to the Alabama Supreme Court. In August, it ruled in favor of Cooper, on the grounds that he has “absolute immunity” from lawsuits, according to the state constitution. Ivey, in a rare public comment on the bridge, welcomed the decision, but focused on its affirmation of the government’s right to build.

The ruling allows the project to resume, but notably, the court declined to dispute any of Pool’s findings. It also outlined a process by which the toll bridge company could seek damages from the state—a prospect that could hike the cost of the project even higher. Following the ruling, the toll company hiked the rate to cross the bridge by 81 percent, the first price increase in over a decade.

In response to questions from The Daily Beast, ALDOT spokesman Tony Harris accused the toll company of charging drivers “tens of millions of dollars while not eliminating traffic jams” and called the price hike “consistent with that practice.”

Citing a public hearing from five years ago, a recent online poll from a local paper, and “recent news coverage,” Harris contended “there is overwhelming support for ALDOT’s project.”

“ALDOT remains committed to relieve traffic congestion with a new, toll-free bridge,” Harris said. He did not respond to a question about the last time Cooper spoke with Ivey about the project. And Ivey’s office did not respond to a request for comment.

Even in a state with a proud tradition of scandals and politicking as hard-nosed as the college football, the Gulf Coast bridge debacle has registered as particularly baffling and bizarre.

“You’re seeing people just make crazy decisions.” said Jonathan Gray, a longtime GOP consultant in the state who has worked both for Cooper and for the bridge company. “It is grossly negligent, bad decision-making that is putting the state in a very bad light and is exposing taxpayers to tens of millions, or hundreds of millions, in damages or wasted money.”

Why exactly Cooper is barrelling ahead, despite the backlash and legal battles, appears to be one of the great mysteries of Alabama politics. There are theories that the past owner of the bridge company rubbed him the wrong way; others suspect something fishier.

To those who know the situation well, the calculations seem to be more personal. Asked why he thinks the director is proceeding as he is, Joe Emerson, a leader of the local anti-bridge grassroots group, answered quickly.

“Because he’s an asshole,” Emerson said. “Napoleon complex-having asshole.” (Cooper stands roughly five-and-a-half feet.)

Gray, who says he considers Cooper a good man, put things more delicately. “My honest answer is, I don't think there's anything corrupt,” he said. “I think there’s somewhere in between stupidity and forgetting the job.”

Regardless of why it is happening, as the fight drags on, many in the region are growing increasingly concerned that real, lasting damage will be done, no matter how it is ultimately resolved.

Beyond the philosophical opposition to wasting taxpayer dollars, burning so much cash on a project that may do very little to address the region’s traffic needs could make it far less likely to get much-needed investment in the future.

Chris Elliott, the GOP state senator who represents the Gulf Coast region, expressed that worry in an interview with The Daily Beast.

“It’s not just, ‘Hey, can that money be better spent in Baldwin County?’” Elliott said. “When it’s time for another bite at the apple for state transportation funding, my colleagues in the state Senate might say, ‘You got your bite at the apple and used it on that?’”

A similar dynamic could play out in the future whenever Alabama seeks federal investment for its various transportation needs, said Gray. And it has plenty of them: Adding an extra lane to clogged Interstate 65, the state’s main north-south corridor, has been a top priority for years. While the Ivey administration announced progress on that front in August, locals believe there is much more work to do.

“Here’s a state with significant infrastructure projects they don’t have money for, they’re having to beg the federal government for money on, and they’re running around spending wasteful money,” said Gray.

Most frustratingly to some locals, after years of negotiations and back-and-forth, they are no closer to seeing relief on the snarled roads leading to the Gulf Coast, which saw over 8 million visitors last year.

“My frustration as a local who represents these folks is we don’t have a solution still,” said Elliott. “There doesn’t seem to be a solution on the horizon.”

Tony Kennon, the mayor of Orange Beach—the town that sits just east of the proposed bridge site—said that if Cooper had accepted the bridge company’s initial offer, improvements could have been completed years ago.

“In all of that time of Mr. Cooper going back and forth, our traffic has gotten worse and we have no solution,” said Kennon.

“That, in and of itself, shows what inefficiency and incompetence we see, out of nothing but arrogance,” he continued. “It’s so unreasonable, I can’t wrap my arms around it. I can’t see why the governor’s office doesn’t see it that way.”

In testimony for the bridge company’s lawsuit, Cooper admitted he had not spoken with Ivey personally about the project since 2017, instead communicating with her chiefs of staff.

The governor, who was re-elected last year, is set to be in office until 2026. Republican officials expressed concern over what they see as an unusual degree of disengagement from Ivey and her office in addressing the bridge situation.

“I do think that the problem here is a lack of leadership and engagement from the governor’s office and from the DOT director,” said Elliott, the state senator.

Kennon put it more bluntly, saying the responsibility for the situation rests with Ivey. “I don’t know if I’ve ever talked about the bridge with her,” he said, adding that he had past governors on speed dial. “She’s never entertained my concerns, or our concerns as a city… I have no earthly idea what’s going on. I don’t know if anyone does.”

Defenses of the bridge rest on the fact that it would be “free”—at least to travel, even if construction was funded by the state’s taxpayers. In court and in public, ALDOT has cast the Baldwin County Bridge Company as acting in the defense of its own profits, not the residents and visitors of the region.

Cooper’s team has argued that the bridge company refused to acquiesce to making improvements to their property, a claim the company and others have vehemently denied. In court, BCBC has claimed to have offered to widen the toll bridge, expand the tolling plaza, and make trips free to Baldwin County residents. ALDOT’s biggest issue in the proposal was the bridge company’s condition that no other bridge be built over the Intracoastal Waterway within 50 years. “This company wanted a promise that their monopoly, which has never worked, would be protected for another 50 years,” an ALDOT spokesman told AL.com in 2022.

But the bridge company has maintained Cooper was never interested in reaching a deal. “They missed that it was negotiable,” said Joe Espy, the lawyer representing BCBC. In his 50 years of practicing law, Espy said, the suit against ALDOT is “one of the strongest cases I’ve ever seen.”

On the substance of the case, that claim could perhaps be true. But in terms of the law, even the bridge’s detractors saw the Alabama Supreme Court’s ruling in favor of Cooper as fairly cut and dry. Alabama law has an expansive vision of state power, giving state agency directors “absolute immunity” from civil lawsuits like the one brought by the bridge company.

Many locals believe the bridge would simply funnel more cars onto the same roadways to the ocean, exacerbating traffic. “I’m in favor of more lanes across the canal—they’ve just got to work,” said Elliott. “The project itself is only a bridge. There’s nothing that indicates that the state Department of Transportation would actually move forward with the connection that gets to the bridge.”

Kennon said the project has drawn the opposition of many of his constituents, but admitted that many have been persuaded by the promise of a free bridge. Elliott, the area’s state senator, was unable to venture a guess as to the share of constituents who support and oppose the project.

Lieutenant Governor Ainsworth, who is seen as a very likely successor to Ivey, has noticeably tried to distance himself from the increasingly toxic debacle.

As Gray, the GOP consultant, put it: “I think the lieutenant governor is saying, ‘I’m likely to inherit this, and you’re essentially taking a dump in the punch bowl, and you’re handing me the punch bowl.’”

It seems a safe bet that, no matter what, the simple issue of how to better bridge that narrow stretch of waterway between Alabama and its gulf coast will not be resolved anytime soon, whether Cooper remains in office or not.

For those already pessimistic about this state and its governance, it’s shocking, but perhaps not surprising.

“When you think Alabama politics,” said Emerson, the local activist, “this is a pretty cut-and-dry case of it.”