For over a decade beginning in 1947, the anti-communist witch hunt that was the Hollywood Blacklist ruined careers, families, and lives. Anyone who came to the attention of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and who refused to name names or publicly denounce communism was put on the proverbial list, the notoriety of which stripped them of their ability for gainful employment. No Hollywood player wanted to be guilty by association.

Director Herbert Biberman was named in the earliest, most infamous wave of HUAC victims known as “The Hollywood 10.” He was sentenced to jail for six months for refusing to answer Congress’s question about his communist affiliation. Producer and screenwriter Paul Jarrico was swept up in the second wave and also stayed silent. Soon after screenwriter Michael Wilson won a 1952 Oscar for A Place in the Sun, he was blacklisted for—you guessed it—refusing to cooperate.

Most of the men who were blacklisted either never worked again or struggled to produce work under pseudonyms or outside of the country. But in 1953, these three men took a different path. They decided to form their own production company to make films they were passionate about, movies about “real people and real situations.”

For their first (and only) film, the Independent Productions Corporation (IPC) decided to tell the story of an important social justice movement taking place in New Mexico where a group of mostly Mexican American mine workers were engaged in a 15-month strike against the Empire Zinc Company.

On viewing it today, Salt of the Earth could be considered one of the most American of movies, a rare mid-century gem that deftly portrays a fight for both racial and gender equality as well as the social justice struggle of an important labor movement. But at the time, any “message movie” that wasn’t pure patriotic propaganda was seen as subversive.

Before even the first frame was shot, the red, white, and blue powers that be in Congress and in Hoover’s FBI heard about Salt of the Earth and saw, well, red. During the length of its production and attempted distribution, the movie became enemy number one. Today, it is the only film considered to have been blacklisted.

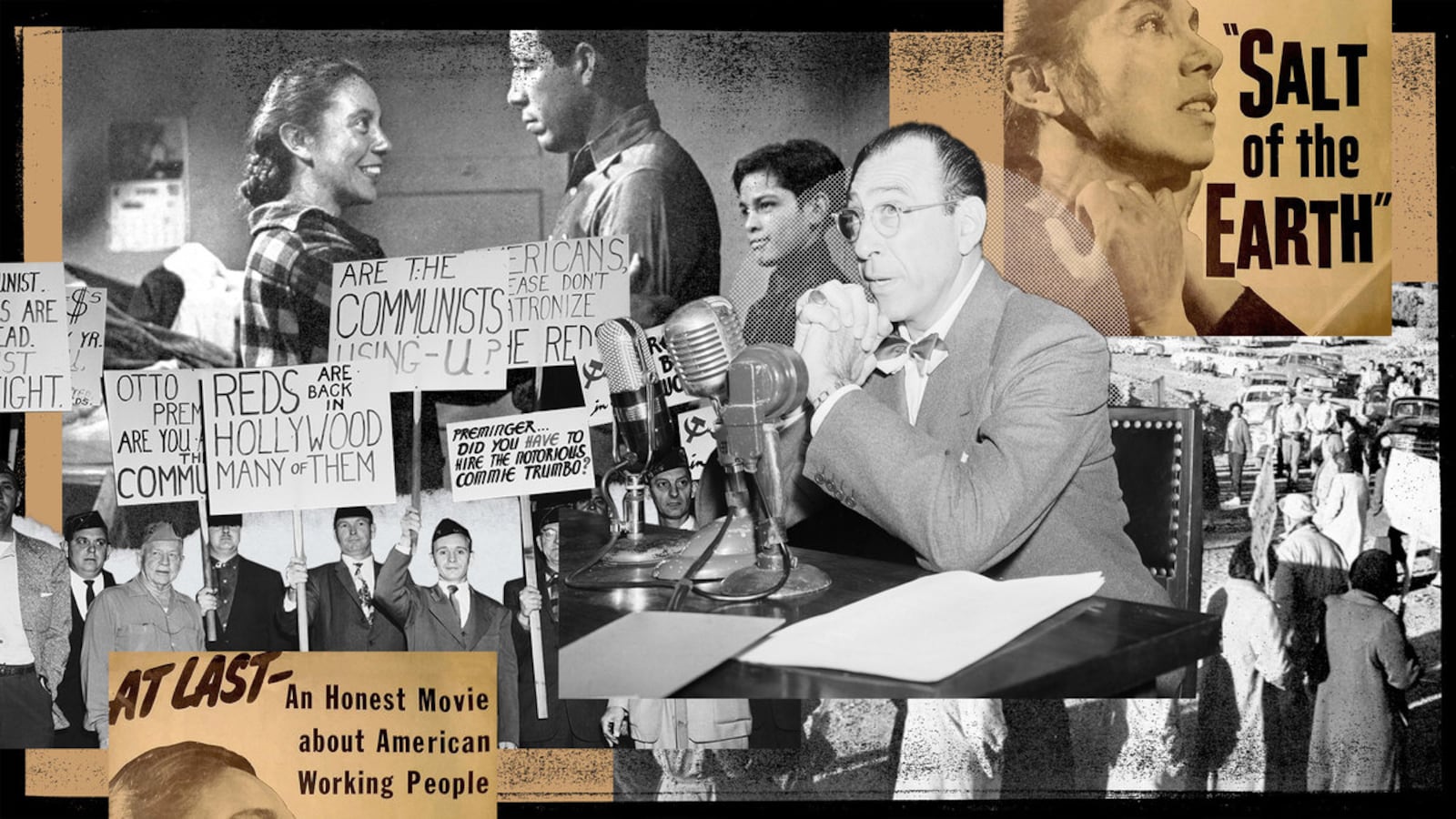

Howard Hughes, center, and Congressman Donald Jackson, right, did everything they could to hinder the production of The Salt of the Earth, left.

Photo Illustrations by Luis G. Rendon/The Daily Beast/Getty/Everett“One of the reasons we made Salt of the Earth after we were blacklisted was to commit a crime worthy of the punishment, having already been punished for subverting the American films,” Jarrico says in the 1983 documentary A Crime to Fit the Punishment. “It was all ridiculous.”

Power to the workers

On Oct. 17, 1950, mine workers and members of Local 890 in New Mexico went on strike against the Empire Zinc Company. The mostly Mexican American strikers were demanding better safety standards at the mine, as well as fighting for pay and living conditions equal to that of their white colleagues. In addition to being paid more, the white miners and their families were given homes that had basic necessities like running water that were denied to the Mexican-American workers.

But there was an added twist to this strike. After a few months, the powers that be invoked the Taft-Hartley Act, which made it a crime for the men to picket. So, their wives stepped in. With the men now watching on the sidelines, keeping the homes, and babysitting the kids, the women spent their days picketing and facing arrest and violence. Their involvement was a win in its own right as the women had to fight to convince the men to allow them to take over and, in doing so, to become sisters in the brotherhood of the union.

From the beginning, well before the powers that be began to weasel their way into the production, Salt of the Earth was not going to be your standard Hollywood movie. Biberman the director, Jarrico the producer, and Wilson the screenwriter knew that they wanted to use actual mineworkers as actors in their film and that they wanted the story to be a collaboration with the real people who had lived it.

As Biberman and Wilson later put it, it was to be the “first feature film ever made in [the U.S.] of labor, by labor, and for labor” and one that “does not tolerate minorities but celebrates their greatness.”

Wilson set about writing the script, not an easy task as his first few attempts were rejected by the strike workers, who thought the early versions didn’t fully and accurately represent their lived experience.

But once the script was ready to go, the members of the IPC threw their full effort into making the movie just one year after the strike had ended. What they didn’t at first realize is that from that point on, they would be dealing not just with the normal problems that plague production, but also with the long arm of McCarthyism.

Early on in the production, Congressman Donald Jackson of California began to crusade against the movie. He sent letters to everyone he could think of asking for advice and help with sabotaging the project. He also took to the floor of Congress to publicly denounce it. Howard Hughes, who had fired Jarrico the minute he was subpoenaed by HUAC a couple years earlier, responded to Jackson laying out all of the steps along the way of production that the government could interfere. (“We can stop them in the labs, we can stop them in the sound studios, we can stop them in the cutting rooms.”)

With these two big names publicly against the film, Salt of the Earth lost many of the actors who had already agreed to star alongside the mine workers, who would be acting after putting in full shifts at the mine. A new slate of actors was secured, with the movie now set to star famous Mexican actress Rosaura Revueltas as the lead and real-life union leader and striker Juan Chacón as her union leader husband.

Securing a cameraman was the next big hurdle. No one in Hollywood would take the job, and the Mexican and American governments collaborated to prevent any Mexican cameramen from getting the proper visas to be able to do the work. So, Jarrico went to New York and found a documentary cameraman willing to take the risk.

Once production began, the problems only intensified. First there were the threats, calls to set to let the parties involved know that they would be leaving the production in black boxes. Then violence broke out, with local vigilantes interfering wherever and whenever they could, including firing guns at the set.

If the physical violence weren’t bad enough, the parties involved also had to deal with the psychological violence of constant surveillance. “There was a point when nobody knew whether they were being followed by the FBI, by [anti-communist Film Craft Union member Roy Brewer’s] boys, or bruisers per se. But the fact is, being followed we were and throughout the making of this film this was one of the greater hazards,” recounted composer Sol Kaplan.

When those steps didn’t shut the film down, the government got bolder. Towards the end of shooting, immigration enforcement came onto set and arrested lead actress Revueltas, claiming she was in the country illegally. They detained and eventually deported her. While Biberman got creative and was able to finish the film with a stand-in, the experience was life changing for 32-year-old Revueltas, who was blacklisted in Mexico and who never had a major role again.

When production wrapped—or more like they finished up enough to be run out of town accompanied by police protection—the filmmakers encountered a whole new set of problems. As Hughes had laid out, they had a terrible time finding studios to finish up the sound and editing of the movie.

Kaplan remembers that in order to produce the music for the film, which at that time was done via recording a live orchestra playing alongside the film, Jarrico had to pose as a representative for a Mexican film in order to rent a sound studio in New York. But they couldn’t let any outsiders see the actual movie, or they would be immediately kicked out. So rather than playing alongside the movie, Kaplan had sheet music with notes telling him when the starts and stops of each scene were. Basically, he and his orchestra had to wing it.

“Every conceivable obstacle was thrown in our path and the fact that we were able to complete the film despite these obstacles was a very heady experience. It was a triumphant experience,” Jarrico said.

Completing the movie might have been an incredible achievement, but what followed was a big disappointment. While the critics who were able to see the film widely praised it, distribution was nearly impossible, so the film fizzled out with very few people having had the opportunity to view it.

Over the decades, that slowly began to change. Early on, a cult following began particularly among labor scholars. Then, in the 1980s, Turner Classic Movies picked up the film and it began to be seen by more and more people. In 1992, the film was inducted into the Library of Congress’s National Film Registry List of significant U.S. films.

Clockwise: Jarrico the producer, Biberman the director, and Wilson the screenwriter of Salt of the Earth all were investigated by the House Un-American Activities Committee.

Photo Illustrations by Luis G. Rendon/The Daily Beast/Getty/EverettBut even as that period of American history became more distant and Salt of the Earth finally began to get its due, memories of the struggles the team went through and the heartbreak of the blacklist never really faded for those involved.

“I did a lot of research and I talked to a lot of blacklisted people, and Paul [Jarrico] was really no different from anyone else,” screenwriter John Mankiewicz tells The Daily Beast. Their experience during the blacklist era was still very much “alive to them…I mean, Paul, in his 80s, if he had encountered someone who'd named names, would cross the street to avoid walking past them.”

In the mid-1990s, Jarrico approached Mankiewicz, grandson of Citizen Kane screenwriter Herman Mankiewicz, about creating a new movie telling the story of the making of Salt of the Earth from the perspective of the main FBI agent who surveilled the production. Jarrico died shortly after their meetings began in a tragic car accident on his way home from an awards ceremony where he was honored for helping to get credits restored for the work of all who had been blacklisted. But over 20 years later, the fruit of that idea is now out in the world as a scripted podcast, The Big Lie. The story may be set in the 1950s, but it could not be more timely.

The story of the blacklist and the making of Salt of the Earth, “has to do with propaganda being used to divide Americans,” Mankiewicz says. “I’ve got the [Jan. 6] hearings on, and it’s really the same thing. It’s dividing America. You know, there’s a whole bunch of people who believe in this Big Lie, in the current Big Lie [of the stolen 2020 election]. And they believe it’s true, just as in the ’50s the American government was saying that communism was the Big Lie.”

In 1976, Wilson received the Writer’s Guild Laurel Award, and gave a moving and prophetic acceptance speech. In it, he said:

“I fear that unless you remember this dark epic, and understand it, you may be doomed to replay it. Not with the same cast of characters, of course, or on the same issues, but I foresee a day coming in your lifetime, if not mine, when a new crisis of belief will grip this Republic, when diversity of opinion will be labeled disloyalty, when chilling decisions affecting our culture will be made in the boardrooms of conglomerates and networks, when the powers of the programmers and the censors will be expanded, and when extraordinary pressures will be put on writers in the mass media to conform to administration policy on the key issues of the time.

“If this gloomy scenario should come to pass, I trust that you younger men and women will shelter the mavericks and dissenters in your ranks, and protect the right to work.”