At 11:20 p.m. on May 13, 2017, two young men and a girl checked into a Hampton Inn. It was a Saturday night, just before Mother’s Day, and the hotel looked like pretty much every Hampton Inn in the world: tan walls, turquoise upholstery, neatly cellophaned apples that could have been shipped anywhere but wound up on coffee tables at the Hampton in Coconut Creek, Florida, right behind a highway, a gated community, and a massive jiu-jitsu gym called American Top Team.

The men didn’t know the girl at all. They had met her only hours before. Later, they would tell officers from the Coconut Creek Police Department that they never even learned her name. In a sworn statement to investigators, one of the men recalled driving to the hotel and chatting to his friend while the girl sat in the back seat, mumbling something about a “lesson learned.” Upon arrival, they booked Room 515 on the top floor, a mid-sized suite with two queen beds, a nightstand, a small bench, a desk, a chair, a dresser, a television, and a microwave cart.

The girl arrived with a small red suitcase, sporting a black shirt, black sweatpants, and black socks with sandals. She wore five rings (three on her left hand, two on her right), two necklaces, a black hairband on her left wrist, and red nail polish, except for on her ring-finger nails, which were painted grey. She covered her black hair in a long blonde wig. The boys, who had no baggage, helped her into the room and left to get food. About 30 minutes later, the police report notes, one of them returned, noticed the girl was in the bathroom with the light on, texted a friend to hang out, and left again to smoke weed. After 45 minutes, he came back to find the bathroom still lit up and locked from the inside. But it was late and he was tired, he told detectives in a sworn statement. He went to bed, fell asleep instantly and didn’t wake up until 7 a.m. Mother’s Day morning, when, noticing the bathroom door was still shut, it occurred to him to call for help.

Within minutes, a hotel employee arrived with a screwdriver and slid the flat end behind the handle, flicking a grooved mechanism that unlocked the door from the outside. When the man saw the girl’s feet overturned on the bathroom floor, he already knew what a police officer would announce some 15 minutes later; namely, that the girl, 16-year-old Jocelyn Flores, was dead.

The death at the Hampton Inn, which was immediately declared a suicide, probably would have drawn scant notice had it not been for an unusual series of events.

Jocelyn’s family was religious, traditional, and private. When an officer called her mother to break the news, they spoke only briefly to confirm a few details. “She did not wish to speak with me much,” he wrote in his report. Later, he received a phone call from her aunt and uncle, who explained the mother would not accept calls any more and that they would be the family contacts. (The mother declined to comment for this article). The family held a small funeral service in her hometown, a suburb of Cleveland, Ohio and, on the whole, handled their grief quietly.

But five days after her death, Jahseh Onfroy, a South Florida musician who performed under the name XXXTentacion (“It means ‘unknown temptation,’” he once told K. Foxx on 103.5 The Beat), released a soft, acoustic track on SoundCloud called “Garette’s Revenge.” The lyrics dealt with death (“I’ve dug two graves for us my dear,” he sings in the hook), a dedication mentioned the girl’s first name, and the album artwork—a black-and-white, partially scratched-out handwritten letter—was her suicide note.

The song attracted some attention. XXXTentacion, often called “X” by fans and friends, developed a cultish following after his song “Look at Me!” took off in January of that year, while he was in jail facing a list of charges that included accusations of extreme domestic abuse.

But the real spotlight didn’t come until three months later, when X dropped an even softer track which, within hours of its release, began to climb the charts, where it would stay for 20 straight weeks. The song’s popularity persisted well into the next year, eventually cresting at double platinum in January of 2018, the rapper’s second single to do so. Just last month, a year and two days after it first dropped, this single ranked as Spotify’s 16th most-streamed song in the country.

The track, which X had titled “Jocelyn Flores,” pulled the girl’s South Florida suicide out of obscurity and made it one of the most famous tragedies of the year in American pop culture.

But Jocelyn’s family knew nothing about the song until one day in August of 2017, when her uncle, who worked valet service at a San Antonio strip club, was parking a car as the radio played. He did a double-take when the title crawled across the stereo screen. “I couldn’t believe it,” he said. “I saw the thing. It said “Jocelyn Flores!” On the thing. I was like, what the hell?”

A common refrain about suicide—and one that Jocelyn’s mother has shared with friends and family—is that it doesn’t take away pain so much as pass it to other people. “Like the worst game of tag,” one friend said. Jocelyn’s death left a crater in the lives of her friends and family, sending some into a deep depression and leading at least one to seek medical attention themselves. But the circumstances of her death—taking her life among near-strangers, and then becoming an icon to millions of actual strangers by way of a song she never even heard—meant that far more people laid claim to Jocelyn’s grief than would be expected in the average suicide.

Her fame hit the Flores family in wide-ranging ways. Some were angry X used her story without permission; others were honored. Jocelyn’s step-sister thanked the rapper on her YouTube series. Her aunt cursed him on Facebook. But however people felt about it, Jocelyn’s name was indelibly tied to X’s. As he navigated his bumpy ascent to celebrity, her story went with him. As his fan base grew, so did the volume of messages Jocelyn’s friends and family received from listeners across the globe, conveying messages of support, asking questions about her life, or confessing their own suicidal impulses—an unsolicited onslaught that often opened the wound of their loss rather than heal it.

“It’s a constant reminder,” Jocelyn’s aunt told The Daily Beast. “It’s like, I’m doing OK today, and then someone tags me on some X story, or likes my picture and mentions X, reminding me that she’s gone.”

The writer Philip Connors once observed that suicide baffles us because it “scrambles our categories of justice” and offends us in a way that little else does. “A crime has been committed,” Connors wrote in The New Yorker, “but the victim and perpetrator are one and the same.” Still, in some ways, the case of Jocelyn Flores seems more unjust than others. Her posthumous celebrity opened her story to the public in way suicide narratives rarely are, presuming a consent that her family never gave. The international success of a single in her name, in other words, raises a question with no neat answer: If suicide spreads pain rather than quash it, then who, exactly, does that pain belong to?

Jocelyn Amparo Flores was born on July 2, 2000, in the Bronx, where her father, Benji Flores, worked in a barbershop off of Fordham Road. According to his brother, Daniel Flores, Benji was particularly good at the edge-up, running clippers along the natural hairline, cutting crisp, clean angles. When Benji was done with his razors, he would break off the blades and store them in a little glass bottle. Once, when Jocelyn was a toddler, she was hanging around the barber shop and found her father’s used razor container. It had nearly a year’s supply of old blades, all super thin and jammed into the jar at odd angles. “She got into it one day and she pulled 10 of the razors out,” Daniel said. “She did not cut her hand. And I was like, ‘This is a fucking miracle’—excuse my Slovakian—but I was just amazed. We were both astounded.”

Jocelyn Flores was born in the Bronx. She was just four when her father died.

Courtesy of Brandee RamirezJocelyn did not skirt trauma for long. When she was four, her father died from a chronic illness he couldn’t afford to treat. Not long after, she would later tell her relatives, a close family member molested her. The two events left Jocelyn with a dark outlook on life, a tendency toward self-harm, and an obsession with suicide she couldn’t easily explain. “My head is just messed up,” she would one day tell authorities, who later sent her statements to the Coconut Creek police. “The doctors can’t do anything for me.”

The first time Jocelyn Flores tried to kill herself, she was just 12 years old. Before the night in Florida, she had been hospitalized four times for taking pills, cutting her wrists, drinking bleach from the bottle, or, once, all three.

Over the course of multiple interviews, family members expressed frustration with the inadequacy of song lyrics, statistics, or psychological assessments to capture Jocelyn’s personality in its full complexity. “They didn’t know the story of Jocelyn,” Daniel Flores said. Between depressive episodes, and sometimes during them, Jocelyn was funny, outgoing, “girly,” and extremely stubborn, her relatives said. She liked to draw. She accompanied her cousin to Girl Scouts and sketched unicorns for them. She wanted to move to New York and go to art school.

“She was a handful. She was always a handful,” her aunt told The Daily Beast, laughing.

Brandee Ramirez, a woman in her late-thirties with a crooked smile that telegraphs instant warmth, first met her niece in 2002 during a visit to San Antonio, Texas, where she lived with Jocelyn’s uncle, Daniel. After Jocelyn’s father died, the kids would come back to Texas every summer to stay with Ramirez and Daniel in San Antonio. In that way, Ramirez got to know Jocelyn as well as she knew her own kids.

In Jocelyn’s Cleveland grade school—the family moved to Ohio after Benji fell ill—teachers would evaluate students’ behavior with a traffic stoplight. Green meant good. Yellow meant alright. Red meant bad. “She would always say, ‘I try so hard to get a green light, but I always get a red. I don’t even get yellow. I always get red,’” Ramirez said. Jocelyn’s brother would always tell her: “It’s cause you’re bossy, Nena.”

Jocelyn's family called her “Nena,” which means baby girl in Spanish.

Courtesy of Brandee Ramirez“Nena,” which means babe or baby girl in Spanish, was the family name for Jocelyn. Though the world now knows her as Jocelyn Flores, in real life no one called her that. “I actually never called her Jocelyn until she passed away,” Ramirez said. “I met her as Nena.” Ramirez did not even know her niece’s legal name until she began buying her plane tickets to visit Texas.

Ramirez occasionally called Jocelyn a “sugar glider,” after the tiny, wide-eyed marsupials (“You know those little animals?” Ramirez said. “How they just hang over the neck and all over your body and just cling on you? That’s how she was. She would come and lay with me and be all over me”). When feeling less affectionate, she called her “Katie Ka-Boom,” after a character in the 1990’s Warner Brothers’ cartoon, Animaniacs, who often becomes enraged by the small injustices of adolescence. When her father, an animated Jimmy Stewart-analogue, imposes curfews, chores, or constraints, Katie’s eyes begin to glow, her face burns bright red, and her small frame explodes into a veiny green behemoth—the Incredible Hulk, but a high school girl.

“That was Nena,” Ramirez said.

The Katie Ka-Boom comparison underscores the tension between a young girl campaigning for independence and a conservative family concerned with what it might bring. Jocelyn wanted to go out with her friends, wear makeup, flirt with boys, and have a drink. Her family, to state it simply, did not want her to do those things.

“She wanted to grow up so fast,” Ramirez told The Daily Beast. “Not a lot of people know she was 16 years old. She looked like she was 24.”

The seeds of rebellion were in Jocelyn from a young age. “She was a renegade,” Daniel said.

In 2011, she spent a summer working at a pizzeria in San Antonio owned by her uncle, who would send employees into nearby hotels to slip menus under guests’ doors. Jocelyn was the best at this job, able to sweet-talk her way into even the fanciest hotels. “She could get into them like nothing, all by herself,” Daniel remembered. “I’m talking old hand, like she’d been doing it for years.” But the gig came to a quick end when her aunt and uncle caught Jocelyn using the hotel trips to sneak away with an older employee and hit the mall or movies.

The constant family feud over control, Ramirez said, is part of what made it hard to hear Jocelyn’s pleas for help. “I thought she was playing me,” Ramirez told The Daily Beast. “She would say, ‘I’m going to kill myself.’ Now, when I think about it, the girl was serious. But at the time, I didn’t know.”

Jocelyn’s depression deepened in adolescence.

Courtesy of Brandee RamirezStill, as her depression intensified, her relatives started to listen. Jocelyn began seeing a therapist, who encouraged the family to let her try new things. They allowed makeup now and then. Ramirez let her go to a few concerts. She got permission to try medicinal marijuana. And later, when Jocelyn proposed flying to South Florida to visit an up-and-coming SoundCloud artist named XXXTentacion, her mother agreed. It wasn’t a choice exactly. Jocelyn had announced that she was going, with permission or not. “She had balls,” Daniel told The Daily Beast. “When she said she was going to do something, she would check you on it. She would be like, watch me.”

The day Jocelyn flew out to Florida, she had not known X for long. According to his sworn police statement, the musician first messaged her on May 2, 2017, just 11 days before her death. Though by no means a celebrity, Jocelyn had acquired a significant social media following in Cleveland. X saw a picture of her on Twitter, thought she looked pretty and sent her a message out of the blue. The two talked, exchanged numbers, and FaceTimed a few times over several days.

It was during a FaceTime call that X proposed the trip. When Jocelyn passed the phone to her mother, he asked for permission to purchase a ticket, and her mother agreed. A vacation sounded nice. Jocelyn had last been hospitalized on Christmas Day, and things were still tense. In Florida, she could relax, have some fun, take a breather. Nine days later, the 16-year-old landed in Florida.

In the past year and a half, little detail has emerged about the days before Jocelyn’s death, the void filled instead by rumors, suspicions and myths. One persistent inaccuracy—an error which bothers some members of Jocelyn’s family—is that she was a model, flown out for a photo shoot. In a short video X made on social media announcing the incident, he said of Jocelyn, “I flew her flew her down here to model, pretty much.” But Jocelyn, before that trip, had never modeled.

It’s true that X had been looking for models. He planned to launch a clothing line called Revenge to promote a new album of the same name. But he told police that he and Jocelyn had not discussed modeling before she flew down and only hired her after she arrived. The visit, by both the Flores family’s account and X’s own, was not professional, but romantic.

“I get it. She was 16,” Ramirez told The Daily Beast. “But he’s over there, making this music about her, and then, he isn’t even honest.”

The nature of the relationship helps explain why things went sour when X invited another girl, identified in the police report only as “Zoe,” to stay with him that same weekend. By all accounts, the first night passed without incident, although tension built between the two girls. On the second day, when X had plans to accompany his cousin to prom, everything fell apart.

Sometime in the mid-afternoon, X left the apartment where they were all staying and made his way to the dance. Hours passed. And when the singer returned that evening, he noticed he was missing around $7,000 in cash, recent earnings from shows, that he kept in a bag.

X interrogated his two house guests about the missing money, but neither confessed. In his statement to police, the SoundCloud star said each girl blamed the other, and tensions came to a head. Zoe had bad-mouthed X behind his back, Jocelyn claimed. When Zoe cut back, the argument escalated with threats of a fight.

At that point, X had been out of jail only 61 days, and the troubled rapper was still very much on probation. He warned Jocelyn and Zoe that they could not fight in his home. They had to leave, he said, and Jocelyn could not model for Revenge anymore. According to three statements to police, X offered to buy Jocelyn a plane ticket back to Ohio, but she rejected it. After X left for dinner, Jocelyn texted him, panicked: Was he serious? Was she really kicked out?

“The conversation ended with Jahseh [X] informing Jocelyn that she could not stay with him any longer,” Investigator Steven R. James wrote in his police report. “The last text message between them was on 05/13/17 at 22:35 hours. This was the last conversation between Jahseh and Jocelyn.”

Ten minutes later, Jocelyn was in the back seat of a car with two members of the musician’s entourage, en route to the Hampton Inn. The following morning, police found her dead on the bathroom floor.

One week after Jocelyn’s death, X started a livestream on Instagram. “This is serious,” he told the camera. Wearing a black hoodie and a chain choker, his hair dyed half-blonde in the style that had already become his signature, he was visibly shaken.

“There was this girl I had basically flew down here to model, pretty much. Great girl, beautiful girl. Wonderful personality. Showed no signs of depression whatsoever. When she flew down here, in an unexplained way, she killed herself when she came down here,” he said. “It was a devastating situation to deal with. I basically got on here today to address her and her family. Because I haven’t been able to contact her family personally. I’m on here to pay my condolences.”

According to Ramirez and Daniel, those were the only condolences the family got from him. Jocelyn’s aunt and uncle reached out to X, messaging him on social media and contacting his mother. At one point, Jocelyn’s step-dad arranged a phone conversation with X’s publicist, but nothing came of it.

“We just wanted to know what her last day was like,” Ramirez told The Daily Beast. “That torments me. I just want to know the last day. Please. Tell me anything. What did she do that day? What did she eat? When was the last time you saw her? Did you take her to Universal Studios like you promised her? What is it that you did with her? What was her last day like? That’s all I asked.”

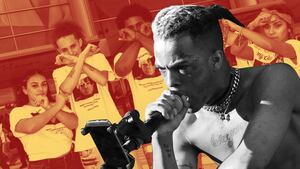

XXXTentacion performs in Miami in May 2017, days before Jocelyn’s death.

Matias J. Ocner/Miami Herald/TNS via GettyNot long after, the rapper left for his tour—performing concerts in 26 American cities, including two in Texas. Ramirez fantasized about crashing one of them, about driving six hours to Houston, walking up to the venue and confronting the guy who had seen Jocelyn the day she died. But when the night of the show came, she stayed home. “I was like, what if I don’t get in? What if I can’t get ahold of him? What if he has somebody kick me or something? I just didn’t know.”

At that point, X’s song “Jocelyn Flores” hadn’t yet dropped and X was still a SoundCloud artist with a small, dedicated following. But two months after the Houston show, the singer uploaded a video to Snapchat with a snippet of a new song playing in the background. This was not unusual for X, who often previewed tracks on social media. Among his core fanbase, these clips were highly anticipated, diligently catalogued and listened to with a nearly religious fervor, so that by the time songs finally dropped, many fans already knew parts by heart.

This snippet was a Russian nesting doll of samples, featuring a beat called “im closing my eyes” from SoundCloud producer Potsu which, in turn, sampled an acoustic track posted on Instagram by a relatively unknown artist named Shiloh Dynasty. X’s fans pounced on it. “I listened the beat of Jocelyn Flores so much ever since the snippet for the track dropped,” a user named SteinsWayLife wrote on Reddit.

Then, 20 days later, the rapper released his first full album, 17, on his own label, Bad Vibes Forever, and Empire Distribution. The record included X’s first Jocelyn-inspired track, “Garette’s Revenge,” now shortened to simply “Revenge,” and “Jocelyn Flores” in full, along with nine other songs. The full-length debut sold 88,000 units in the first week, and quickly climbed to No 2 on the U.S. Billboard 200. The day after it dropped, platinum rapper Kendrick Lamar tweeted out an endorsement. “Listen to this album if you feel anything,” he wrote. “Raw thoughts.”

XXXTentacion’s mugshots after a 2017 arrest

Miami Dade County CorrectionsOver the next year, the SoundCloud star would only become more famous, both because of his music and growing concern over his criminal allegations. In September 2017, the music review website Pitchfork acquired the court documents detailing the domestic abuse charges against him and published an extensive summary, including details that the rapper had fractured his girlfriend’s face and threatened to penetrate her with a barbecue tool. The brutal account incited widespread outrage and prompted many music publications to stop covering him. But when X released his second record, ?, in March of 2018, it debuted at No 1 on the Billboard charts, and racked up the second largest streaming week of the year.

Each week that spring came with some new development, some scandal or surprise that kept X in the headlines. The polarizing SoundCloud artist seemed to tap into the zeitgeist of a fraught political and cultural moment, capturing the American attention and making it impossible to look away. Both widely loathed and deeply beloved, there was no denying that he was on the cusp of something, even if no one knew exactly what that thing was.

But then, in mid-June, as the 20-year-old drove out of a motorcycle dealership in Deerfield Beach, Florida, two men approached his black BMW and shot him dead in broad daylight. They made off with his Louis Vuitton bag, where X still kept large quantities of cash.

The news of X’s death at first filled Ramirez with a perverse kind of pleasure: “I was like, karma.” For more than a year, she had harbored resentment for the rapper, who never responded to her messages, and who she suspected, however faintly, had played some kind of coercive role in her niece’s suicide. But above all, what bothered her was what she perceived as X’s exploitation of her family’s pain for the promotion of his music. He “didn’t even give us the courtesy [of] saying hey, I’m going to do this, I hope you guys are OK with it!” she wrote in a lengthy Facebook post. “Nope! No courtesy there! Using [Jocelyn’s] death for publicity!”

The murder unleashed a renewed interest in the music, including “Jocelyn Flores” which quickly returned to the Billboard Hot 100, and peaked at No 19 in late June. The Flores family was again bombarded by messages and tribute videos, only now to Jocelyn and X together, which Ramirez liked even less. Often the videos played “Jocelyn Flores” in the background, a song the grieving aunt had tried hard not to hear.

In July, there was an unsettling development: An account appeared on Instagram under Jocelyn’s name. The handle was slightly different—Jocelyn posted under @realjocelyng and this person used @jocelynflores_x_x_x—but the page updated often, occasionally posting photos Ramirez had never seen. She messaged the user: Who are you? Why are you posting pictures of my niece?

When the account replied, Ramirez learned it was operated by someone named Emily Petraglia, a thirtysomething fitness instructor and mom who spends half the year in Pennsylvania and the other half in Parkland, Florida, just miles from where X had lived. Petraglia had never heard of X before June, but once his murder made the news, she did some research, listened to his music, and stumbled onto the story of Jocelyn Flores.

X’s song struck a chord with Petraglia. Her father had died when she was young. As a teenager, she had tried to kill herself, and she fought depression into early adulthood. Sometime last year, one of her childhood friends, whom she hadn’t seen in a while, took his own life without explanation, leaving the young mom with the lingering feeling that maybe she could have done something differently. As Petraglia learned more about X, his music, and his relationship with Flores, she noticed that many of the rapper’s fans (who, on the whole, skew young) described suicidal impulses similar to those that she had felt as a teen, and that she imagined Jocelyn had felt before she died.

“I started seeing his following, and how hard these kids were taking his death,” Petraglia told The Daily Beast. “They were all suicidal. I figured if I was this curious about Jocelyn, probably all these kids were curious too. So, I found photos of her online, and I made the page, for anyone who needs help or is confused or wants to figure out life.”

Petraglia’s observation tapped into the very real problem. In the past two decades, suicide has been on a grim upward march in the United States, with the annual death toll around 45,000 a year—a 25 percent increase since 1999. Teen suicide has tripled since the 1940s, according to the Centers for Disease Control. One in six high school students reports that they have seriously considered taking their own life. And a CDC study shows Latina girls like Jocelyn are more at risk than black or white girls. Suicide is now America’s 10th leading cause of death, one with no easy treatment.

The phony Jocelyn account was Petraglia’s unconventional attempt at therapy, and it seemed to have instant appeal. The morning after she created the Instagram, she woke up to 15 messages. Four weeks later, she had been contacted by almost 300 kids. One girl wrote and said X’s death made her want to die. A 14-year-old from Mexico worried he would stay a virgin forever. Another boy, not even in his teens, told her he was depressed because he was short–just 4 feet 9 inches. “It’s like, you haven’t even hit puberty yet,” Petraglia counseled him.

In Jocelyn’s name, Petraglia dealt with breakups, family troubles, abuses, spats, unexplained spells of sadness, and sometimes simple loneliness, alienated teens looking for friends. “If I have two or three 12-year-olds,” Petraglia said, “I’ll connect them. I might start a Facebook page, so they have a platform to become friends.”

Although Ramirez was initially disturbed by the copycat account, she came to embrace it. The publicization of Jocelyn’s death had seemed like a massive injustice, a bizarre corruption of the most private pain. But this odd Instagram account seemed like it could right that wrong.

After the famous chronicler of depression William Styron shared his struggle in the New York Times and found himself inundated with messages, he wrote that it felt as though he had “helped unlock a closet from which many souls were eager to come out and proclaim that they, too, had experienced the feelings I had described.” It was, he wrote in Vanity Fair, “the only time in my life I have felt it worthwhile to have invaded my own privacy, and to make that privacy public.”

The Flores family did not choose to have their privacy invaded, but Petraglia helped to make it feel worthwhile. The account wasn’t exploiting Jocelyn’s tragedy so much as extending her story to kids on the cusp of repeating her mistake. It was, in its own weird way, a gesture the late teen would have liked. “I know that Jocelyn would have loved it,” Ramirez said. “She would have loved that she was remembered, that she was helping people. This was her dream. This was what she wanted.”