Hana has a secret. She slowly moves her straw through the whipped cream in her designer latte and looks up. “I’m a rotten girl.”

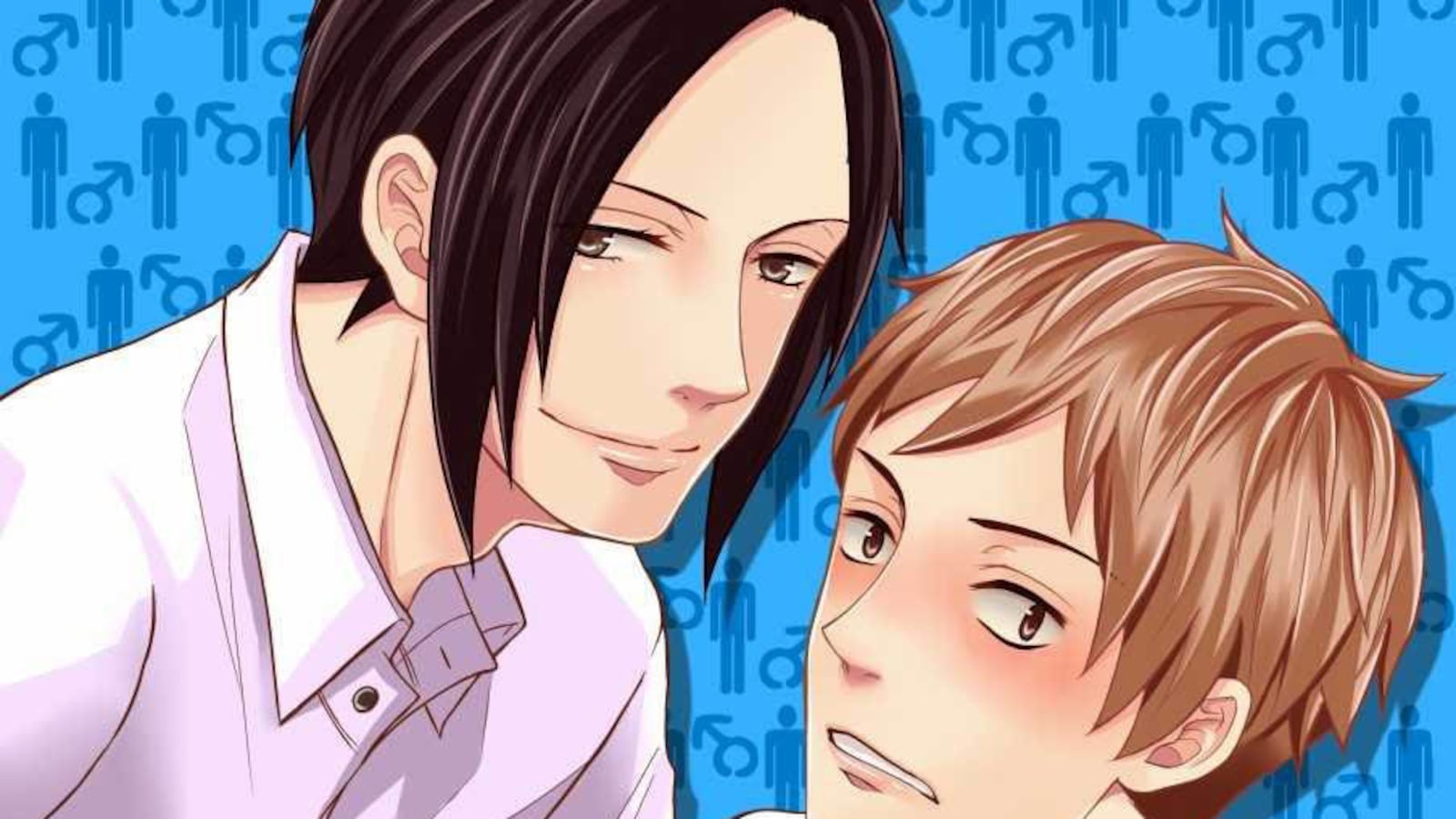

Rotten girls, or fujoshi in Japanese, is a self-inflicted term used by women throughout the country who fall under a certain category of ardent manga (comic book) and anime (animation) fandom. They’re obsessed with what is called BL, or Boys’ Love—fictional stories that detail the romantic entanglements of two men.

While Tokyo’s neighborhood of Akihabara is known worldwide as the center of otaku culture—a veritable capital of geek-dom, if you will—female enthusiasts tend to congregate beyond of the spotlight in Ikebukuro, on the other side of the city. They flock to Otome Road, or “Maiden’s Road”, a wide-set boulevard with a parade of animation-related boutiques selling everything from collectable figurines to thousands upon thousands of comic books.

Hana seeks refuge from the buzzing lights of Otome Road in a nearby café and makes another swirl with her straw. She’s come prepared with notes, like any good otaku, and shuffles her pages of penned thoughts like a deck of cards. She’s never told anyone about her ten-year obsession with BL comics and wants to make sure she gets it right.

“BL is not gay,” she begins, “this is the most important thing you need to know.” The cover art of most of the comics, however, depicts two males embracing, which can make it difficult for the foreign eye to separate a homosexual romance from the themes at hand. But to a rotten girl like Hana it’s all about “pure love”. In fact, the entire genre itself is squarely targeted at a straight female readership and is almost always created by female artists as well.

For Hana, the appeal of BL is largely about the beauty of what she calls a “genderless love.” The fact that it’s two males means she can’t consciously or subconsciously insert herself into the narrative and can thus appreciate the growing romance from afar, like watching a flower blossom.

“When a love exists between a boy and girl, the reader will automatically have empathy with the girl. When it’s just boys, the reader engages in the story from the third person.”

The other problem, according to Hana, with the love between a boy and girl, is that it comes with a lot of societal pressures, like marriage and pregnancy, that can sully the purity of romantic desire. Hana sees great disparity in her country’s gender gap, citing a World Economic Forum’s report, which finds Japan towards the bottom of the gender equality list.

BL has become Hana’s fantasy world where two people are drawn together for no other reason than the simple fact that they love one another and strive to overcome any impeding obstacles in order to be together.

Patrick Galbraith, a visiting researcher at Sophia University and author of The Moé Manifesto, has spent years in Tokyo studying the explosion of BL superfandom, which, according to his findings, pulls in more than $120 million annually, and accounts for roughly 4% of all printed manga in Japan.

Although many young women like Hana prefer to keep their comic book predilections a secret, Galbraith estimates that there are well over a million self-titled rotten girls in Japan, which has created myriad sub-genres within the BL universe.

Galbraith explains that Boys’ Love is also called yaoi in Japanese, an acronym used to reference the homoerotic relationship of two males for a female audience that stands for “no climax, no punch line, no meaning.”

Stories within the yaoi canon run the spectrum of explicitness, from narratives that delicately hint a romantic connection between two characters to full-blown, explicit male-on-male erotica. While the plotlines cater to an immense variety of hyper-specific fetishes within the genre, they all follow a similar course of action that can be parsed into four sections.

“The first part of the story details the initial attraction between the two main characters,” says Galbraith “which usually involves the seme—sometimes called the attacker or inserter—pushing himself upon the uke, a softer and perhaps weaker character who is usually considered the protagonist.”

Although Galbraith cites “rape as a common motif fueled by extreme love,” the most crucial element of the narrative’s first section is the crescendo of tension between the two potential lovers.

The second chapter of the procedural is what Galbraith calls “the relationship realized” when the two male characters overcome a physical barrier and initiate the sexual component of their affection, which can range from a single kiss to something far more explicit.

The final two sections broaden the storyline by throwing a wrench in the main characters’ plans to be together. “Oftentimes their friends disapprove of the relationship, one of the lovers runs away, or a third lover is introduced,” adds Galbraith. “Much of the drama that transpires towards the end of the story is due to the pure love itself, not in spite of it.” But ultimately the two characters lovingly reunite.

Hana delights in the procedural elements of Boys’ Love storytelling, but is most drawn to one particular type of yaoi: fan fiction. Unlike the iterations in Western culture, fan fiction manga is articulated with as much professional finesse as the real thing, and is so incredibly popular that most rotten girls prefer it to commercial fiction.

What’s so compelling about BL fan fiction is that much of it is based on shonen manga—comics specifically geared towards a male audience.

Female readers comb through popular male-dominated storylines involving sports teams or cadres of soldiers and reinterpret a lingering pat on the back after a slam-dunk as the kindling needed to spark a compelling BL relationship. Oftentimes hatred too—like warriors in opposing clans—can ignite the fires of romance in the alternate universe of Boys’ Love literature.

“While commercial BL fiction almost always follows the four narrative stages, fan fiction—which is usually much shorter in length—often ends when the relationship is realized sexually,” says Galbraith. This is largely due to the fact that the characters are well known entities in Japanese pop culture, and the reader’s pleasure is derived in seeing these two characters develop stronger feelings for one another and eventually achieve a certain amount of sexual intimacy.

“Whether or not we want to acknowledge it, the love between two men has been in Japanese culture for as long as we can remember,” adds Hana. “Boys’ Love is a thing of beauty in the kabuki theatre of the Edo era.” (This classical form of dance-drama undertook many homoerotic themes in its Shakespearian depiction and execution of urban narratives in the 17th and 18th centuries.)

"It’s also found in the intimate shudo relationships between an older and younger samurai long ago.” (Shudo, practiced well before Edo times, partnered experienced warriors with adolescent males in an apprenticeship and social-learning role that was heavily sexualized.)

“We self-deprecatingly call ourselves rotten girls because we indulge in this obsession with pure love even though society tells us that it’s a waste of our time. It’s like some kind of self-torture,” Hana says, laughing. “But this rotten girl wonders if the Boys’ Love genre is purely Japanese,” she takes one final spin with her straw—“what’s a Bromance?”