Keke Palmer’s Nope heroine, Emerald Haywood, struts through life with a charismatic, ineffable confidence that dares the world to question her. Early on in the film, however, she receives a warning that seems to rattle her resolve at least a little. The advice strikes at the heart of the film’s ideas about spectacle and brutality, and it becomes even more fascinating in context of the film’s ending. (Warning: Spoilers ahead.)

Nope takes off when Em and her brother OJ (Kaluuya) realize that an apparent UFO has been hovering above their financially imperiled horse ranch for months. The siblings smell a business opportunity: If they can get a good shot of this thing (say, an angle spectacular enough to get them a spot on Oprah) they reckon their lives could really turn around for the better.

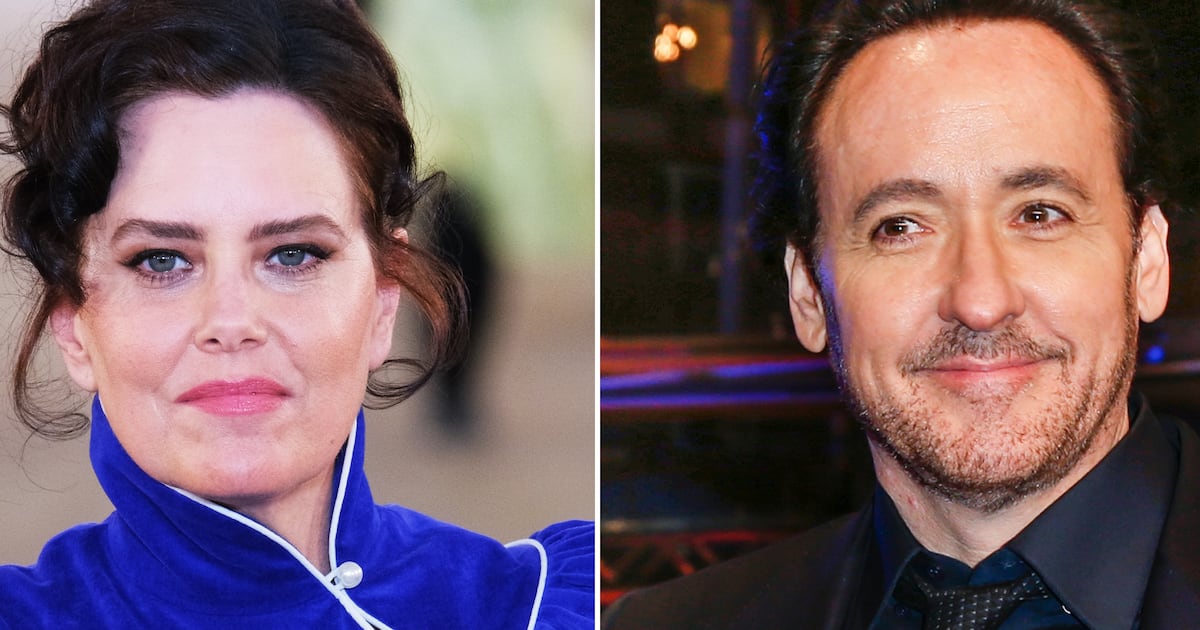

But when Em reaches out to venerated nature cinematographer Antlers Holst (Michael Wincott), he bursts her bubble in an instant: “This dream you’re chasing… where you end up at the top of the mountain?… It’s the one you never wake up from.”

The words are just vague enough to invite speculation. (Does Antlers mean the dream can never be achieved—or that a person who has attained it cannot go back to the person they were before? And what is “the dream,” anyway? Fame itself, or the recognition and adoration that some associate with fame?) Whatever they mean, they seem to unsettle Em, but not enough to dissuade her from her version of “The Dream.” It’s time to get that “Oprah shot.”

What does it mean, though, that Em does get the shot? This thing that was supposed to be unattainable, this thing we’ve never seen, this thing that has eluded photographers for ages… Was Antlers wrong? (Lesson learned, never trust a guy who shows up to a shoot in a David Rose-like hoodie; he will charge straight into an alien’s mouth, handheld camera in-hand, with all the groundbreaking footage he just shot for you.)

With their cinematographer down and all their footage gone, Emerald figures out another way to capture the giant alien they’ve been fighting in a motion picture. Inside the doomed theme park Steven Yeun’s character operates, Jupiter’s Claim, there’s a wishing well that snaps photos of the sky from the ground. Em begins loading the machine with coins and cranking its wheel as the alien flies above the camera, capturing a series of shots she can string together just like her great-great-great grandfather did with the first images of a jockey riding a horse.

Nope’s ending, then, comes right at the REM stage of the dream Antlers described, where all the possibilities (good and bad) come to life. Will the siblings wind up on TV, or maybe go viral? Will anyone believe the pictures are real? If they do get their moment of fame, will Em and OJ be able to parlay that into long-lasting prosperity?

Given Nope’s underlying misgivings about humanity’s exploitative impulses, those questions might be beside the point.

What will it mean if the shots Em got of the alien overshadow the massacre that befell bleachers full of innocent tourists roped in by Yeun’s Ricky “Jupe” Park? Even if Em and OJ do manage to extract some money from this horror show, will they actually be able to process any of what they experienced? Or will they allow the trauma to fester in the back of their minds like Ricky did?

For Ricky, performance became the enemy of introspection—a method of distraction. But that need not be true for everyone. OJ, who’d likely never call himself a “people person,” avoids talking as much as possible when surrounded by strangers in the beginning but finds his spotlight during the alien invasion. More importantly, the “performance”—riding up and down the road on horseback to lure the floating manta-like alien in front of the cameras—becomes an opportunity for OJ to comment on his family’s erasure from traditional Hollywood.

According to Nope lore, OJ and Emerald’s great-great-great grandfather was the jockey first seen riding on screen in the first-ever photos strung together to create a motion picture. In spite of the company he started, the Haywood family never received their place in Hollywood legend. Partway through the film, OJ and Emerald wryly remember their father’s efforts to train horses for The Scorpion King, a project that wound up going with camels instead, once again cutting them out of the myth.

OJ has no interest in fame, and his riding before the camera—in a Scorpion King hoodie, at that—carries all the more meaning for that. Far from an act of vanity, it is an act of historical correction. At least, it would be for those who know the history behind it. It’s a futile question, given that Antlers disappeared up the space-manta’s throat with the OJ footage, but one still wonders: Would the video carry the same meaning for spectators who don’t know the full story behind it?

But the film doesn’t quite end on Palmer’s character snapping the photos. The emotional beat that brings the film home lands just afterward, when Em looks up at something the audience can’t see. The look that screws Palmer’s face is inscrutable, something deeply felt—either tragedy or joy. Then we see it: She’s looking at her brother and realizing, yes, he’s alive. Whatever comes of the video, Emerald seems to have woken up from the dream.