While fighting to keep the labor movement pure, Victor Riesel became a walking, wounded symbol of unions’ corruption, when a thug blinded him with acid.

It was April, 1956 and post-war, pre-Sixties-crime-wave New York City felt like the center of the universe. Cars still had fins. Men still sported fedoras. Ladies and New York cops still wore gloves. But America was starting to “Rock around the clock.”

The Guys and Dolls who ate cheesecake and gossiped at Lindy’s around-the-clock felt they were at the epicenter of the center of the world. Night after night, they spied the television comedian Milton Berle there, and evoked the spirit of Damon Runyon, whose savvy, New Yorky stories immortalizing Lindy’s inspired the 1950 Broadway hit and 1955 Hollywood blockbuster “Guys and Dolls.”

Exiting Lindy’s, his hangout, with his secretary and a friend, at 3 A.M. on April 5, Victor Riesel was a real-life version of a Damon Runyon invention. This gruff, tough street kid wielded his silky smooth pen as a sword to keep labor unions clean. That night, he was probably feeling the buzz that comes from writing a sharp, righteous, commentary and broadcasting a successful radio segment advancing his crusade against organized crime in the transportation and engineering unions.

Traditionally, American workers pragmatically preferred “pure and simple,” “bread and butter” unionism, improving wages and working conditions. Europeans and American Communists embraced radical unionism, affiliating with political parties and demanding sweeping reforms. Beyond these two sides was American unionism’s squalid underside. Corruption wormed its way into the labor movement, curdling its soul with overpaid union bosses and under-worked no show jobs, derailing its mission with payoffs and shakedowns, draining its credibility as a movement founded to champion the poor often enriched thugs and megalomaniacs.

Victor Riesel was born into a union family, living in 1913 on New York’s Lower East Side. “We lived and fought,” he later explained regarding the Jews and Italians in his ‘hood. “Good bloody stuff. Everybody loved each other. There was no racial feeling. Some of the kids went on to prison, and some went on to the universities.”

Riesel claimed he became a union devotee when he was 17 and saw “a grown man weeping. He had no job. His family had nothing to eat.” But it was the family business. Riesel’s father Nathan led Local 66 of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union, proudly brandishing the Bonnaz Embroiderers’ No. 1 card. Victor considered the ILGWU “one of the cleanest, most decent unions.” Nathan Riesel fought for the five-day week and resisted Communist and underworld takeovers of his union. He died in 1946—crippled by a 1942 beating by mobsters.

“My father taught me a hatred of totalitarianism and the underworld,” Riesel said. “He taught me not the priggish, stereotyped kind of honesty but a sense of the eternal value—it was a philosophical concept, really—of disdain for hypocritical piousness wherever you found it…. He believed the trade unionists when they called each other `brother' and 'sister'; he believed what they said about `fraternity' and `freedom'.”

Riesel’s columns perpetuated his father’s values. Even as a student at Morris High School in the Bronx where the family moved when he was 13, he sent out dispatches about union activities to newspapers—selling the same story multiple times in different regions. Night school in Baruch College, day jobs in factories, and on-the-job training in college and union newspapers convinced him he wanted to write about labor not be a laborer.

World War II solidified Riesel’s mid-century liberalism. He championed the working class. He supported the New Deal’s welfare state. And he loathed Nazi and Communist totalitarianism.

In 1941, the New York Post hired him. By 1942 he was editing its Labor Page while syndicating his column “Inside Labor.” Yes, Americans then tracked the ups and downs of workers, labor leaders, and the labor movement as avidly as we follow markets, gazillionaires, and the celebrity culture today.

Riesel warred against mobsters’ “gorilla warfare.” “My father taught me a hatred of goons,” he recalled. “The first chance I got, I went after them.” He denounced “organized crime muscling in on the industrial front-factories, shipping, the garment business.” He railed against the mob’s “terror tax … raising the price on everything from clothing to artichokes -- anything that could be delivered.” He was equally harsh on Communists, cooperating with the FBI to out “Reds.”

In 1956, Riesel was swinging hard against Teamsters’ attempts to control key supply routes and an unholy Communist-mobster alliance to infiltrate unions at strategic ports in New York, Philadelphia, and the Gulf. On April 2, 1956, he bashed shakedown rackets. Two nights later, his “Three Star Extra” radio show hosted two Long Island rebels resisting the hoodlums controlling Local 138 of the International Union of Operating Engineers. "It's a tough mob, and it's tied in with the toughest mobs in New York and Chicago," Riesel charged, hailing his guests: "It's a lot more difficult to be a celebrity when it means taking your life in your hands, when it means that you might come home to your wife and kids with your head batted in." He also blasted Jimmy Hoffa, the corrupt, ambitious Teamsters leader.

After the show ended, Riesel retired to Lindy’s. Near his car at 3 on April 5, 1956, just outside the Mark Hellinger theatre where My Fair Lady was playing, a 22-year-old thug threw sulfuric acid in Riesel’s face.

Jimmy Hoffa was with some teamsters, including one Hoffa critic, Sam Baron. Hoffa excused himself to answer the phone. Returning, he poked Baron’s chest and crowed: “Hey, Baron, a friend of yours got it this morning.”

“What do you mean?” Baron wondered.

“That son of a bitch Victor Riesel. He just had some acid thrown on him. It's too bad he didn't have it thrown on the goddamn hands he types with.”

The attack backfired. Riesel received 60,000 get well cards, along with 1100 offers of eyes to transplant. People demanded a crackdown. Mobsters soon rubbed out Riesel’s attacker—two middle men were arrested, and within a year the United States Senate Select Committee on Improper Activities in Labor and Management was investigating Hoffa, the Teamsters, and the mob. That triggered Hoffa’s feud with the McClellan Committee’s zealous chief counsel, Robert F. Kennedy.

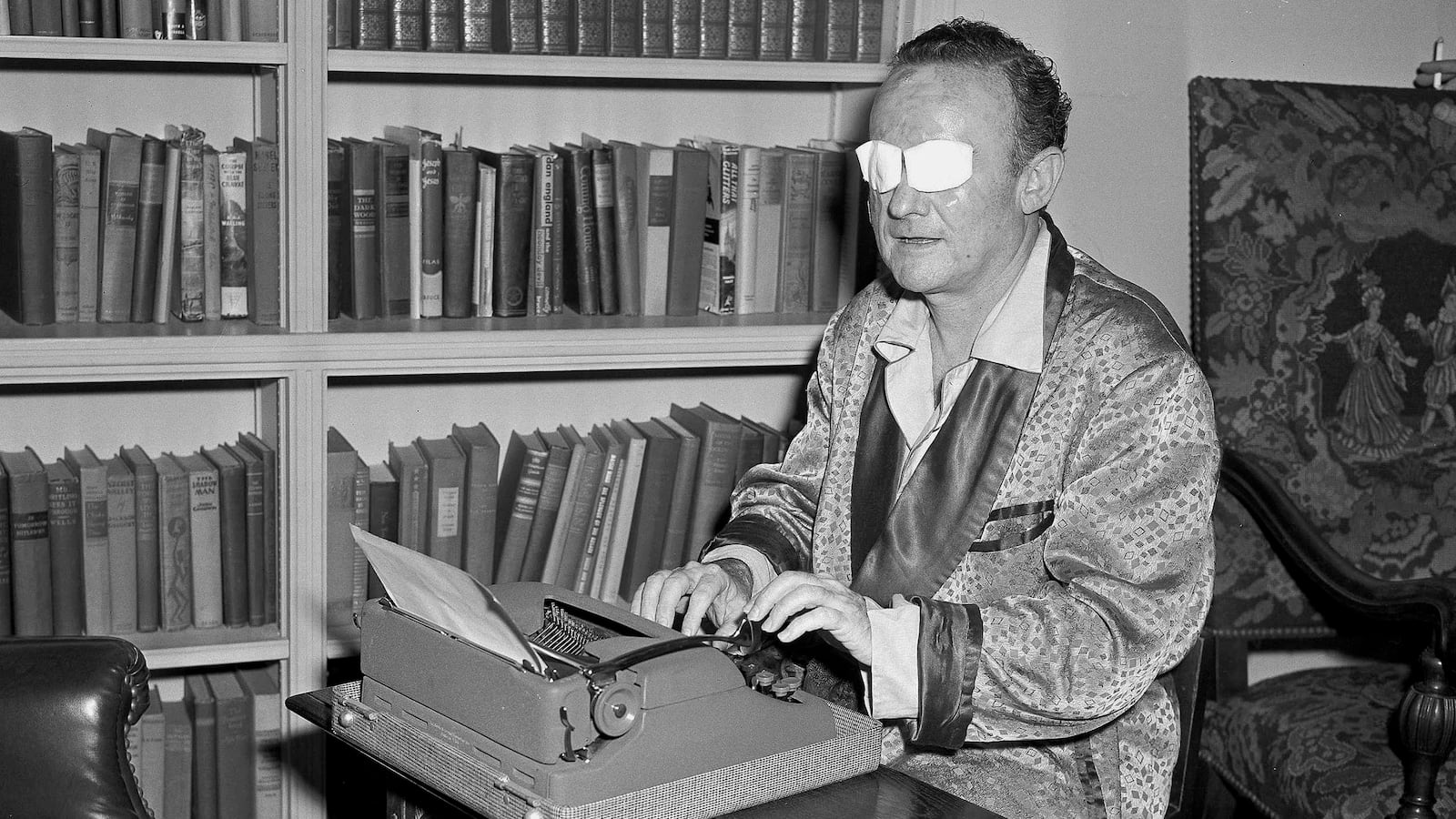

A classic New Yorker, Riesel first considered himself a “chump” for having been blindsided. But remembering his Morris High touch-typing class, he typed out: “Now is the time for all good men to come to the aid of themselves without feeling sorry for themselves.” Back working, he urged union members to "fight for decency" in their locals. Soon, 350 newspapers were running his column, up from 193. In the 1970s, he appeared occasionally on New York’s Channel 5 WNEW-TV, sparring with the arch-conservative Dr. Martin Abend. He, with his dark sunglasses, and the two with their thick, staccato, New York accents, often verged on caricature.

Yet their duels demonstrated an important political shift. While cast as “the liberal,” Riesel disdained the New Left, student radicals, Black Panthers, and New York’s descent into crime, grime, and red tape. Writing his column until 1990, five years before he died, supporting Ronald Reagan with other blue-collar former liberals, Riesel believed Reagan’s claim was true, that “I didn’t leave the Democratic Party, the Democratic Party left me.”

Similarly, Victor Riesel’s epitaph could read: “I never betrayed the American Labor Movement, but vast parts of it betrayed me—and millions of others who needed it.”

FOR FURTHER READING

Pete Hamill, The Lives They Lives: Victor Riesel and Walter Sheridan: In Defense of Honest Labor, 1995.

Philip S. Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the United States, 1991.

Rick Ball, Meet the Press: Fifty Years of History in the Making, 1998.